$1.5T for 1.5°C: a ‘back of envelope’ budget to save the planet

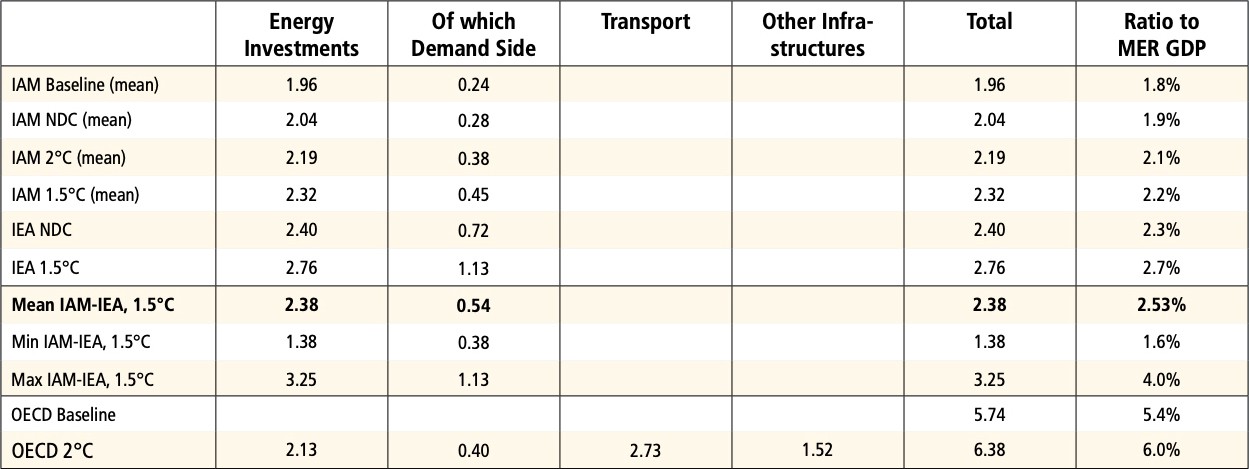

How much will it cost to limit global warming to 1.5°C? Chapter 4 of the 2018 IPCC report Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR1.5) presents an estimate of the combined investments required to limit global average temperature rise to 1.5°C above early industrial levels, landing on a mean of roughly $48 trillion over 20 years, or $2.4 trillion per year for energy investments alone (summarized in Box 4.8, Table 1).

The models incorporated in the study however assume a heavy, ongoing reliance upon fossil fuels, resulting in what we believe is an inflated estimate. These models miss out on huge savings from the elimination of mining, processing, and transporting of fossil fuels, and they also bake in expensive (and largely unproven) Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies.

Box 4.8, Table 1 of the IPPC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, showing estimated annualized global mitigation investments needed to limit global warming.

One Earth funded a major research effort with German Aerospace Center (DLR), University of Technology Sydney (UTS), and University of Melbourne to model an alternative scenario that achieves net-zero carbon emissions before 2040, and near-zero gross carbon emissions by 2050 (with a low level of ongoing emissions in the industry/cement sector) through a rapid transition to renewable sources of power, heat, and fuel, alongside nature-based carbon dioxide removal.

The energy transition model is one of the most detailed to date and was published in book form as Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals (APCAG) by Springer Nature (Teske, S. ed. 2019). A new study is in the works that incorporates the 2020 dip in emissions and a post-COVID recovery scenario to keep us on track for a “good chance” (66%) of limiting warming to 1.5°C globally with a stricter carbon budget:

Some clear benchmarks

To get a more accurate understanding of the investments and policy measures needed to achieve 1.5°C, the APCAG model developed a transition scenario divided into 72 sub-regions. The model maps available sun, wind, water, geothermal, and biomass resources; current grid and pipeline infrastructure; and limits to minerals required for utility components, in hourly increments to 2050. This allows for the creation of a detailed, optimized pathway to decarbonize energy for all sectors by region, including a trade-off analysis of grid storage and load shedding (in many cases batteries can be reduced or eliminated by oversizing solar and wind arrays at lower cost). The model also repurposes existing gas pipeline infrastructure for the distribution of hydrogen fuel.

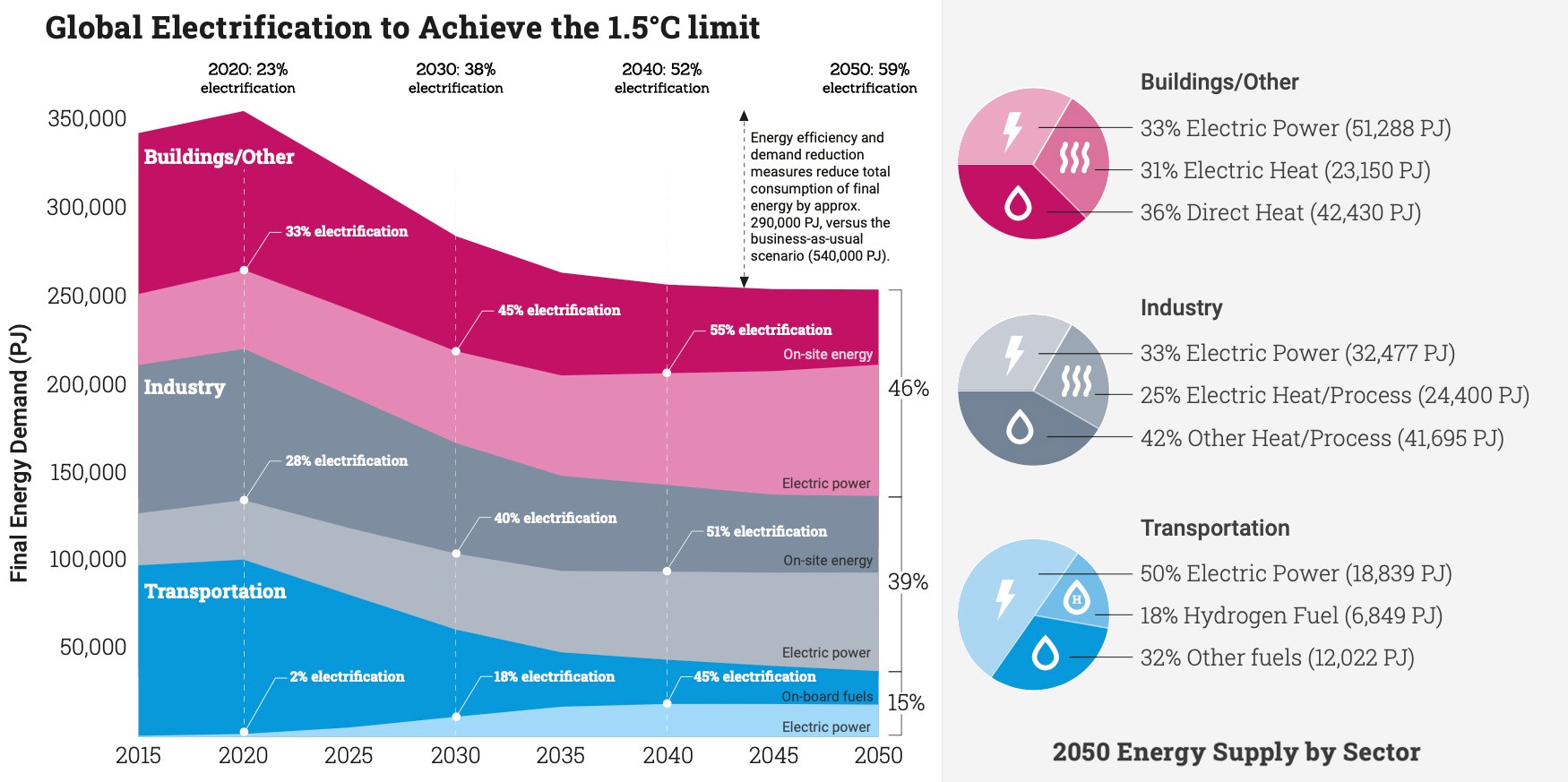

The regional transitions are summarized in the F20 Executive Briefing “Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals in the COVID-19 era” (PDF), which presents clear benchmarks for global decarbonization by mid-century. Globally, the model calls for 38% electrification of total energy demand for transportation, industry, and buildings by 2030 (up from 23% today); 52% by 2040; and 59% by 2050:

All three sectors are increasingly electrified through 2050. Transportation moves from 2% electrification to 50%. Industry moves from 28% to 58%, with a large amount of heat/process demand met through electrified heat in 2050. Electrification of the Residential/Other sector moves from 33% to 64%, with nearly half of heating demand met by electricity. Note: Total energy demand is decreased through energy efficiency and demand reduction measures.

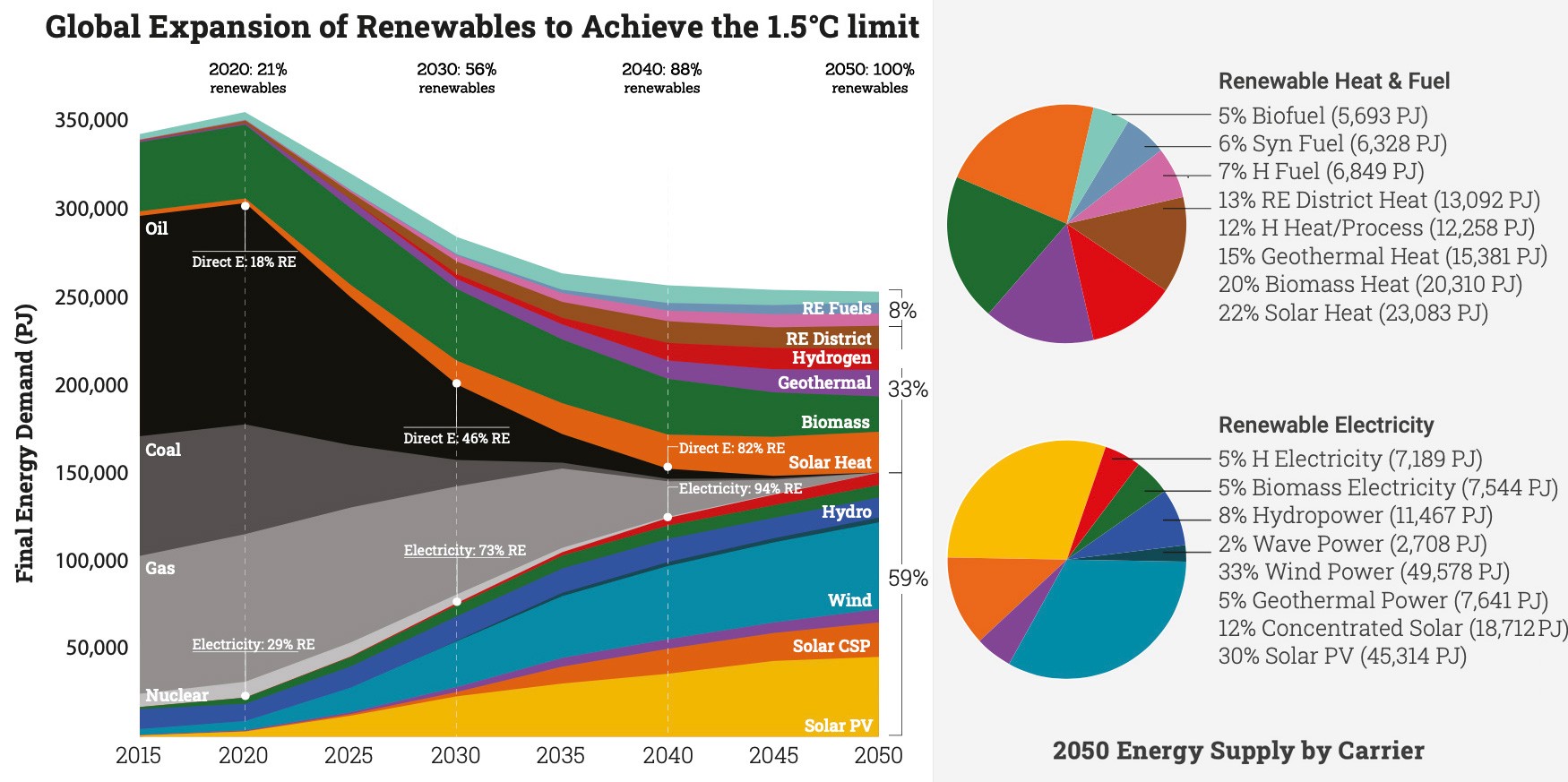

In the APCAG model, approximately three-fifths of total energy demand is met by renewable electricity sources like wind and solar power, and two-fifths is met through direct heating carriers and liquid fuels. 16 distinct energy sources are optimized for maximum efficiency, scaling to 56% renewables by 2030 (up from approximately 21% today); 88% renewables by 2040; and 100% renewables by 2050:

Coal, Oil, and Gas are gradually phased out as electricity demand is met increasingly through renewable power generation, while fossil fuel-based liquid fuels are replaced by renew- able fuels. Fossil fuels required for building heat and industrial processes are also phased out as renewable solar, geothermal, and other forms of renewable heat are ramped up. In 2050, approximately 59% of total final energy demand is met by renewable electricity.

How much will the energy transition cost?

A detailed economic model puts the price tag for the APCAG 1.5°C global transition at $51 trillion for power over a 35-year implementation period, which includes electricity for the production of hydrogen fuel, and another $12 trillion for heating, mostly for heat pumps, solar heating, and geothermal — $63 trillion in total over a 35-year finance period — or approximately $1.8 trillion per year.

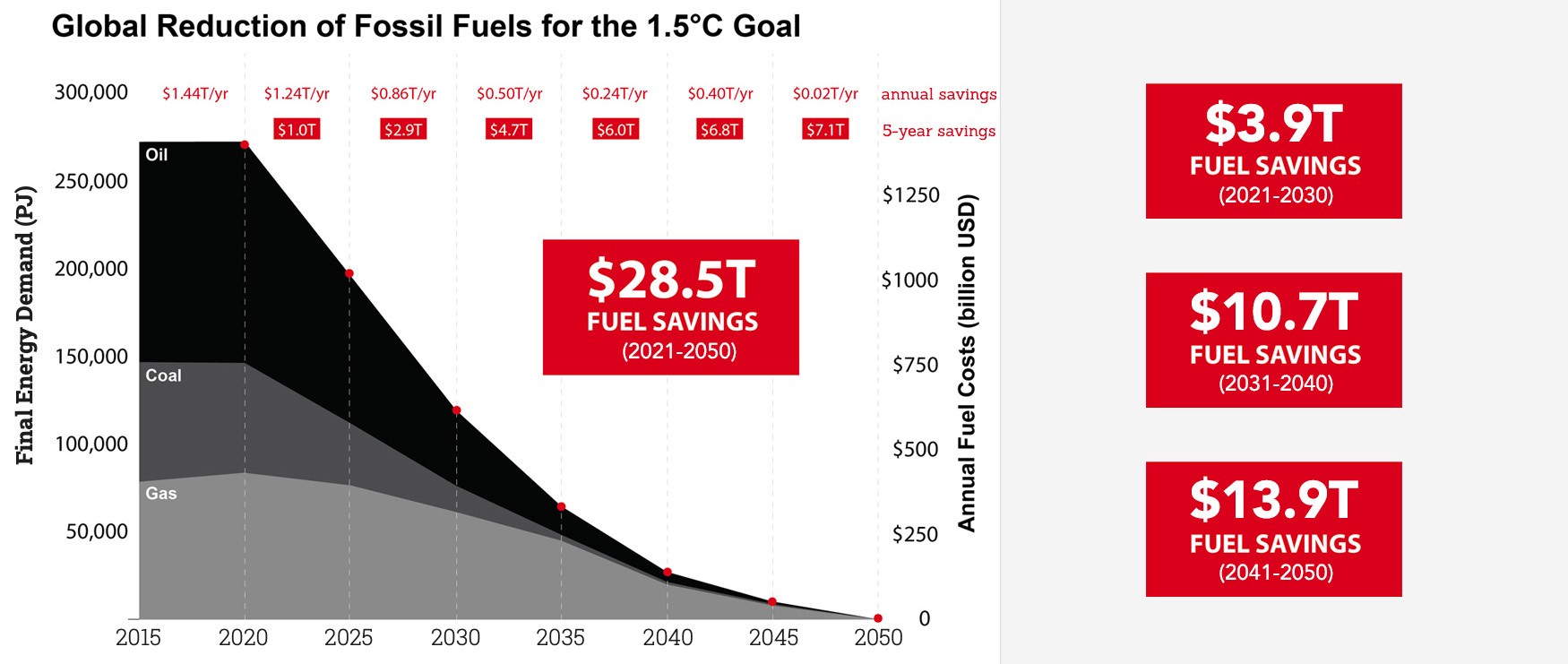

But something often missed are the enormous savings that will result from eliminating the mining, refining, and transport of fossil fuels, which are heavily subsidized by governments and investors. The APCAG model estimates a total of approximately $15 trillion in input fuel savings between 2021–2040, or roughly $750 billion per year. So the net cost of the transition to decarbonize our global energy system, reducing fossil fuel emissions by approximately 90% by 2040, is about $1.05 trillion per year:

Avoided costs of extraction, processing, and transport of fossil fuels through a rapid transition to 100% renewables by 2050, based on APCAG 2019 (1.5C scenario).

Now, this does not include specific investments in energy efficiency. With a rapid transition to renewable energy, a great deal of efficiency is “baked in”, including the avoidance of thermal power losses and cooling demand. APCAG does not provide an exact estimate of required energy efficiency investments, but we take the lower range of the IAM-IEA mean estimate, $380 billion per year. Taken together, total net costs to get us on an optimized pathway to 1.5°C is approximately $1.43 trillion per year.

The least expensive way to remove carbon

Nearly all 1.5°C climate mitigation models require a lot of carbon removal — between 400–600 GtCO2 removal by the end of the century. In the scientific literature, this is often achieved through theoretical technologies like Bioenergy with Carbon Capture & Sequestration (BECCS) and Direct Air Capture with Carbon Storage (DACCS). While certainly there are some small CCS and Direct Air Capture pilots in operation, their costs have proven exorbitant and require significant energy inputs that cannot be met sustainably over the long term at scale. Several experts on One Earth have pointed out the many problems with BECCS and DACCS.

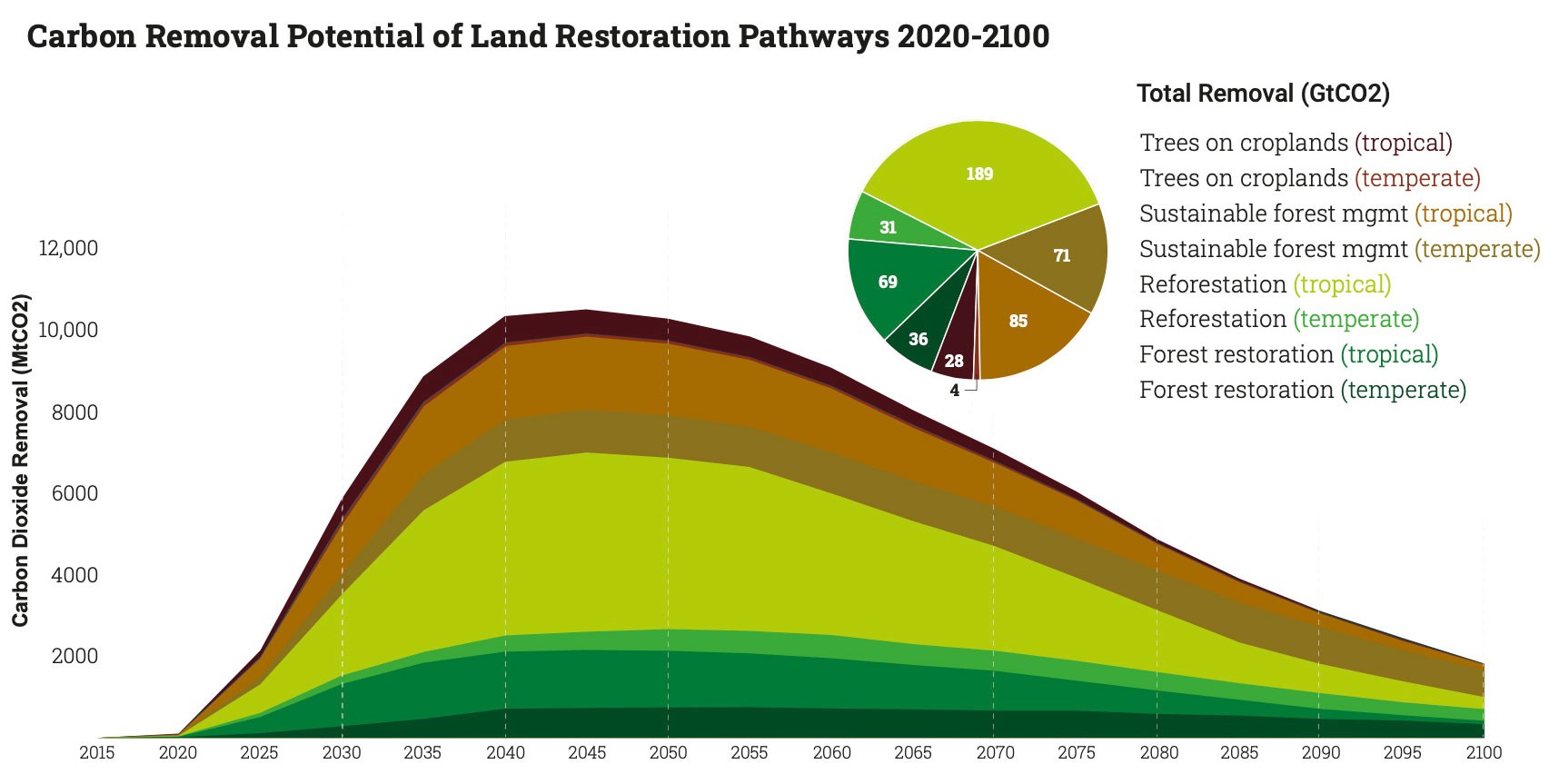

The alternative, of course, is the humble tree — a 350 million year-old technology that reliably removes and stores carbon. APCAG asked the question, is there sufficient technical potential of forests to absorb the 500 GtCO2 of carbon removal required to have a good (66%) chance of limiting global average temperature rise to 1.5°C? The scientists who authored Chapter 4 of APCAG did a meta-analysis of scientific literature on four well-documented forest pathways, identifying a technical potential of 513 GtCO2 carbon removal by 2100. These are divided into tropical and temperature zones:

- reforestation (replanting native trees on degraded lands)

- natural forest restoration (regenerating degraded forests with minor interventions)

- sustainable forestry management (reducing tree harvests)

- Afforestation (tree planting) on degraded croplands where appropriate

APCAG presents a statistical analysis of the time horizons and potential cumulative carbon uptake for four major forest restoration pathways, divided in temperate and tropical zones. The chart shows total potential carbon removal of 513 GtCO2 through these pathways, with a rapid deployment beginning in the 2020s.

There are relatively straightforward cost estimates for each of these pathways:

- Reforestation. APCAG identifies 220 GtCO2 of potential carbon removal from reforestation. — 300 Mha of tropical land and 50 Mha temperate land. Costs are roughly $3450/ha for tropical and $2400/ha for temperate = $58B/yr over a 20-yr implementation period 2020–2040.

- Forest restoration. APCAG identifies 105 GtCO2 of potential from natural forest restoration over 600 Mha of degraded forest. We assume 1/10 the cost of reforestation or an average of $300/ha = $9B/yr over a 20-yr implementation period.

- Sustainable forestry. APCAG identifies 155 GtCO2 of potential removal through reduced logging and better forest management at zero cost (achieved through policy measures).

- Trees on croplands. APCAG identifies 30 GtCO2 of potential removal from tree cropping on 400 Mha of agricultural land and assumes one-tenth the cost of reforestation or an average of $300/ha = $6B/yr over a 20-yr implementation period.

To recap, for nature restoration APCAG finds 513 GtCO2 of carbon removal potential for the four major pathways, which would cost roughly $73B/yr to implement fully. A new research paper is currently establishing the technical potential of carbon removal for additional restoration pathways, including silvopasture, grassland restoration, mangrove/coastal restoration, and peat/wetland restoration. Even with a rapid transition to renewables, 95% or more of this potential would need to be realized.

Bringing it all together

Combining net energy investments of $1.43 trillion per year with $0.07 trillion per year for forest restoration, we land on a back-of-envelope budget of just a little over $1.5 trillion per year to achieve the 1.5°C goal of the Paris Climate Agreement.

It’s important to point out that there is a lot this estimate doesn’t include — investments in high-speed rail, industrial advances, utility infrastructure, protection of our natural terrestrial and marine carbon sinks, shifts to a more sustainable agricultural system, and climate adaptation measures that will be necessary as global temperatures continue to rise. Many of these investments would be required under any scenario and are difficult to quantify.

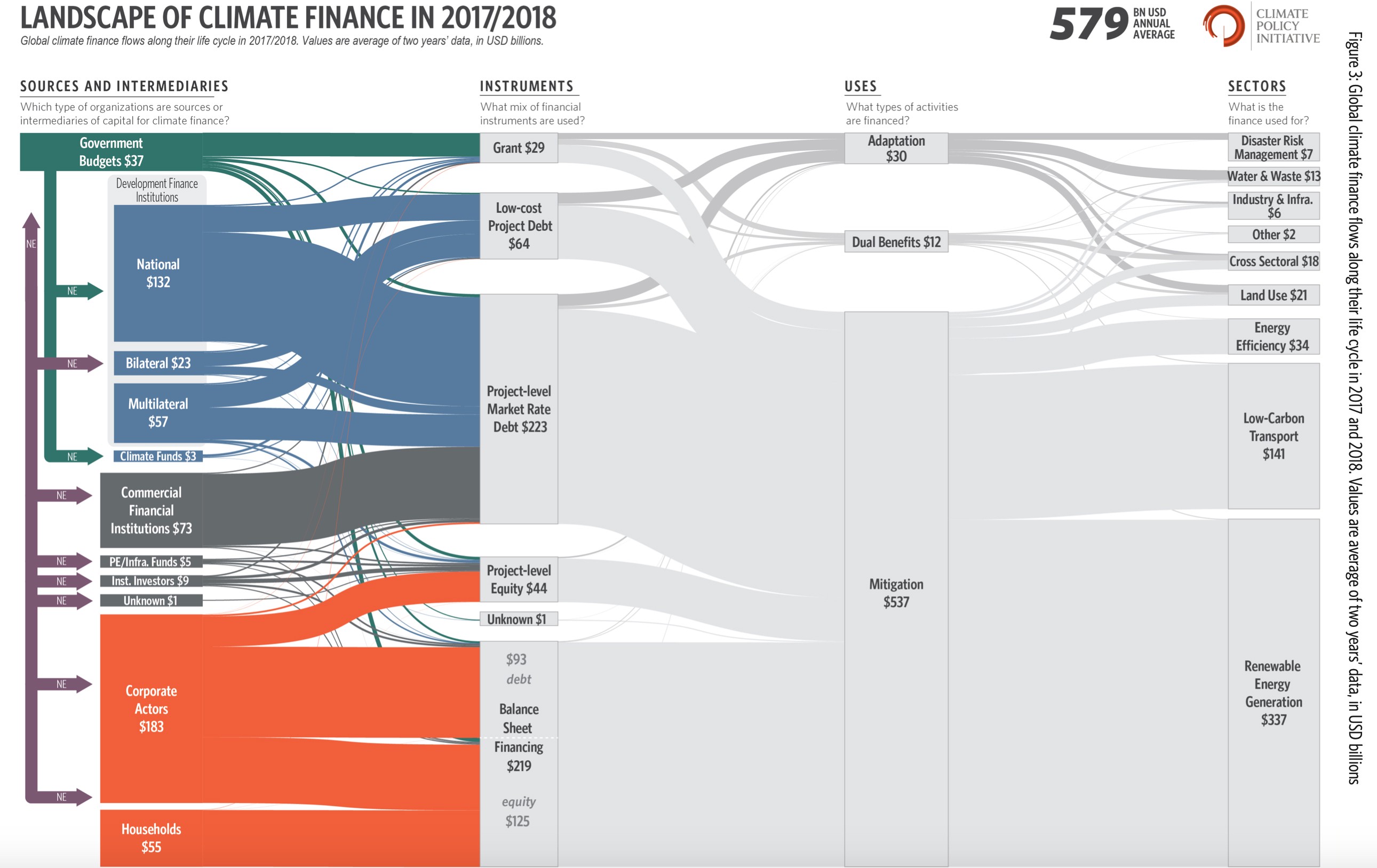

But our back-of-the-envelope budget does give us a clear (and coincidentally easy to remember) estimate of the core budget of additional investments needed to get the world on a sensible 1.5°C pathway. And the good news is that we’re already about a third of the way there. The latest estimate of current capital flows from public and private finance by the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) is now well over $500 billion per year:

Sources and intermediaries of climate finance by instrument and sector, totaling an estimated $579 billion over the 2017–2018 time frame, with $537 billion directed to mitigation efforts — $337B for renewables, $141B for transport, and $34B for efficiency.

The back-of-the-envelope budget to save the planet makes the daunting endeavor seem much more doable, offering hope in dire times. We don’t need to invent new sci fi technologies to get us out of the climate crisis. What we need to do is triple current levels of investment in climate mitigation, targeting that funding to the right things — a rapid shift to renewables and nature-based carbon removal.