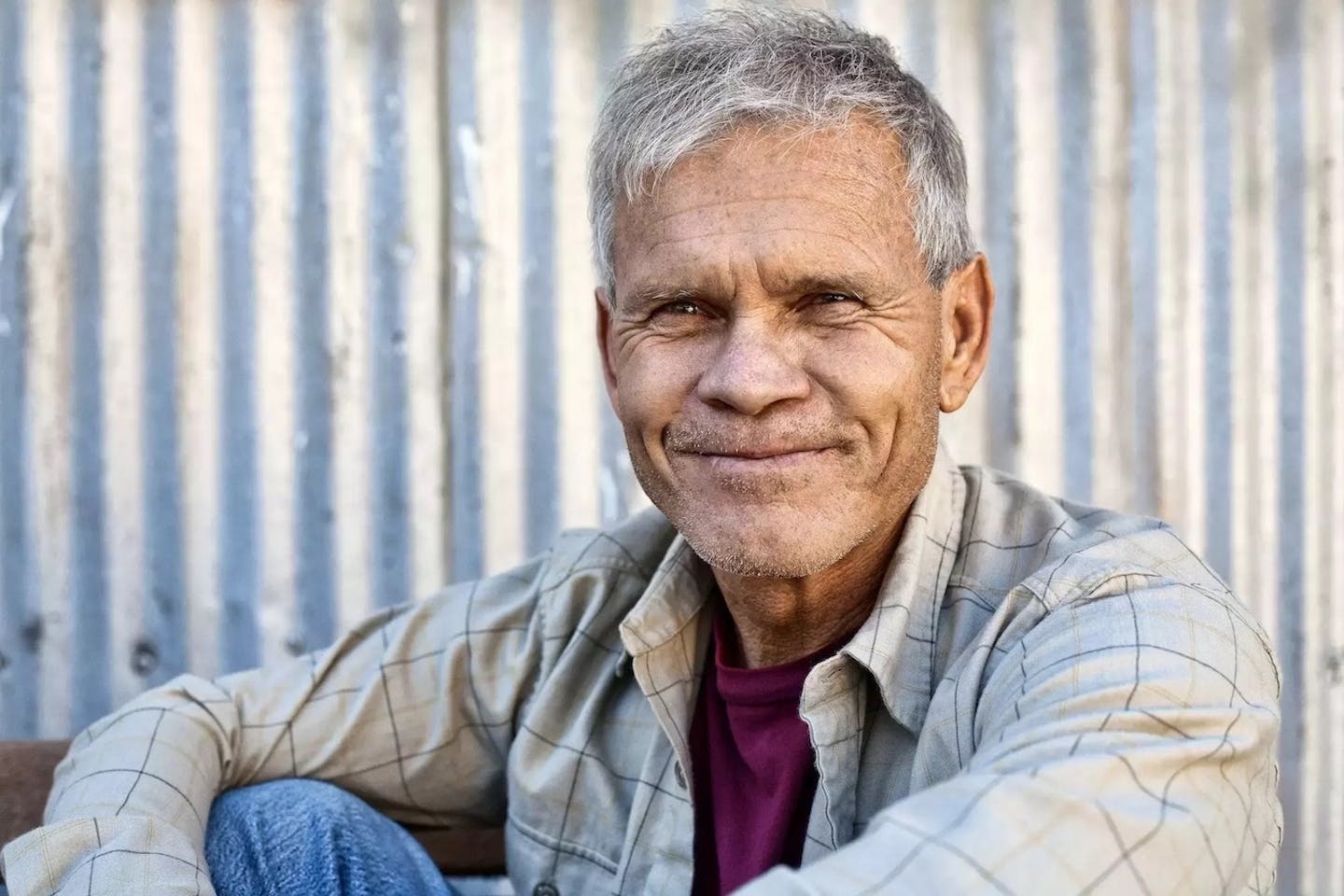

Climate Hero: Rick Ridgeway

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Biodiversity

- Philanthro-activism

- Climate Heroes

- North Pacific

- Northern America Realm

A world-renowned mountaineer, businessman, author, and filmmaker, Rick Ridgeway has spent his life adventuring to some of the most isolated places on planet Earth. Bringing everyday people along for his wild rides through books and documentaries, he has always emphasized profound respect for nature and a call to conservation in his work. His career includes being the Vice President of Environmental Affairs at Patagonia Inc., co-founding the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, and joining the board of the Turtle Conservancy.

Born to be wild

Growing up in Southern California when Orange County was still rural, Ridgeway spent much of his childhood exploring the Santa Ana Riverbed with his buddies. As the area became more developed, he escaped to the hills around the Los Angeles Basin as a teenager.

Driving his motorcycle into the wilderness to hike eventually gave way to climbing. Ridgeway bought equipment such as an ice ax and crampons and taught himself how to use them. Early on, it wasn’t just about the thrill of the climb but the connection to the open country and the wild animals.

A National Geographic piece about the first American climbing Mount Everest caught Ridgeway’s eye, and he began climbing the LA mountains in the winter, covered in snow and ice. Causing his mother some alarm, she sent him to an outward bound school as a graduation present so he could learn some fundamental mountaineering skills.

Image credit: Courtesy of Rick Ridgeway

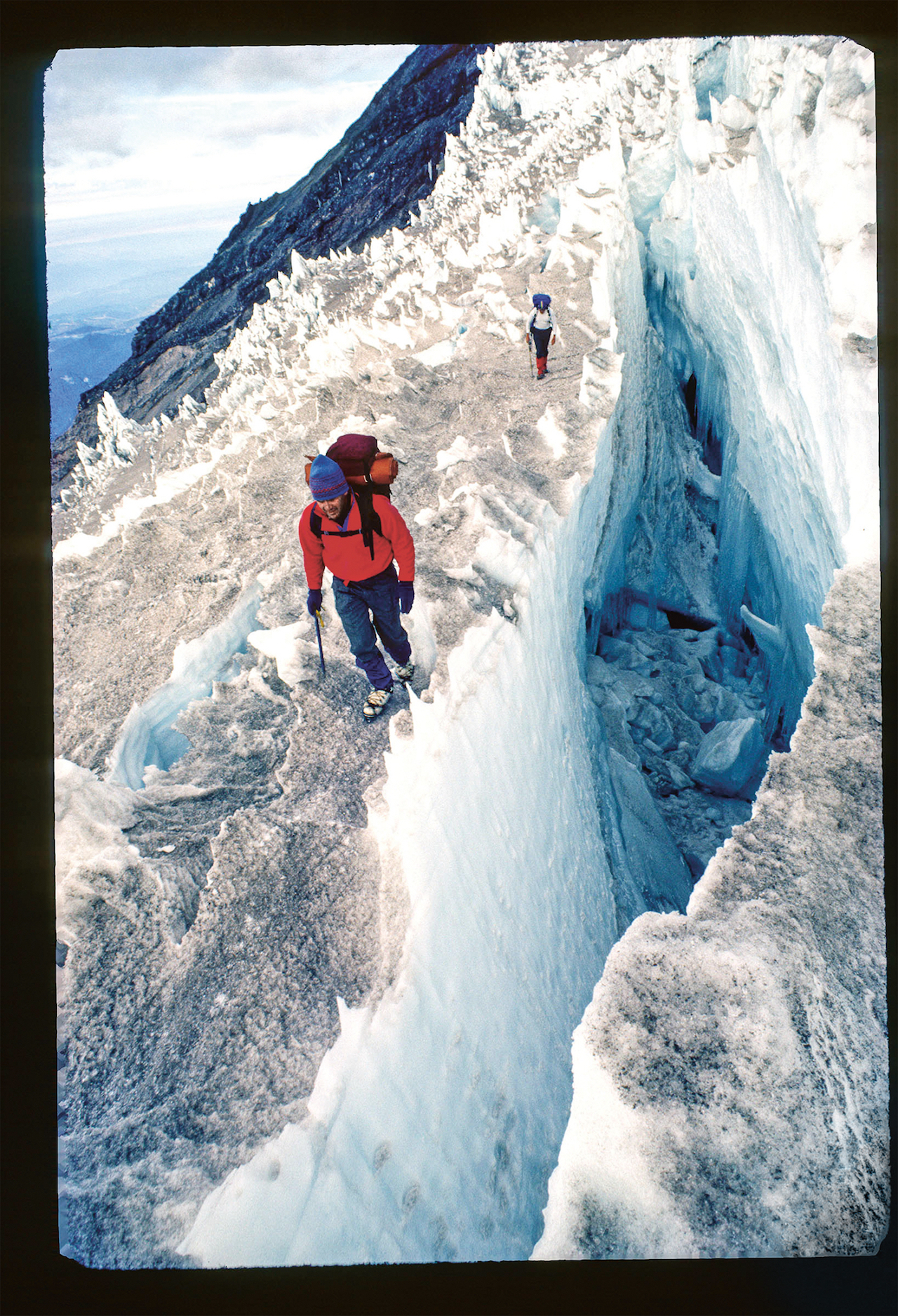

Ascending to the top of the world

In 1976, Ridgeway joined the American Bicentennial Everest Expedition. Two years later, he and three teammates were the first Americans to summit K2, the world's second-highest mountain and most dangerous. It was a massive achievement as it was only the third ascent of the mountain, the first ascent without using oxygen, and the group climbed the Northeast Ridge, which has never been repeated.

The climb significantly influenced Ridgeway's self-confidence about what he could accomplish if he stuck with something and didn't give in or give up. This tenacity began to tie into his love for nature. There was no single epiphany, but the more time he spent in the wilderness, the more he started to see human interference, and the more he wanted to protect and safeguard the wild.

Saving the Tibetan chiru

One of the most fulfilling experiences was when Ridgeway and fellow climbers Galen Rowell, Conrad Anker, and Jimmy Chin used their mountaineering skills to follow the migration of an endangered species of Tibetan antelope known as the chiru. Increasingly threatened by poaching, biologists were concerned that if anyone learned where the female chirus gave birth before environmental protections could be put into place, the animal would be lost forever.

On a 275-mile trek across Northwestern Tibet, the team carried their supplies and followed the chirus’ migration on foot. Their month-long journey was documented in a movie, a National Geographic article, and Ridgeway’s book Big Open: On Foot Across Tibet's Chang Tang.

The publicity galvanized the Chinese to create a protected area and raised money to support the government in establishing patrols in the region. Since then, poaching has gone down, and the number of chirus has been increasing.

Image credit: Courtesy of Rick Ridgeway

In the business of doing good

As Ridgeway continued to explore the world, he also ventured into business. First, for the Kelty Pack Company, where for 25 years, he assisted in marketing and product development. Then in 1987, Ridgeway created Adventure Photo & Film, becoming the world’s largest stock photo and film agency specializing in nature and adventure images.

During this time, Ridgeway had sparked a friendship with Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, Inc. The two would surf, climb, and have family hangouts. When Ridgeway sold Adventure Photo & Film in 2000, Chouinard offered him a position overseeing Patagonia’s global environmental initiatives.

While Ridgeway was experienced in conservation and environmental efforts, he had to get up to speed on sustainability and how to manufacture products with the least harm to people and the planet. With this mission in mind, he organized the Sustainable Apparel Coalition because, at the time, there was no consistent way of measuring sustainability in the apparel and footwear industry.

Today, it's the largest trade organization in the entire industry, with nearly half of all global production for apparel and footwear as members. Ridgeway also developed the Higg Index, an enterprise-level software system that measures thousands of different data points on the entire value chain in consumer goods manufacturing. Companies can now demonstrate a year-over-year reduction in their impact on the environment and increase social justice.

Image credit: Courtesy of Edith Espejo

Conserving turtles and the climate

Retiring from Patagonia in the summer of 2020, Ridgeway began devoting his time serving on several boards of directors of conservation and sustainability organizations, including the Turtle Conservancy. Living in the middle of the conservancy based in Ojai, California, Ridgeway is surrounded by over 600 turtles and tortoises across 30 different species. Most are critically endangered, and a few are already extinct in the wild.

Ridgeway is also the chair of the board here at One Earth, a role he calls “deeply fulfilling and gratifying” and labels as the source of his optimism, “that we human beings are going to overcome the crises that we're facing and save ourselves and the planet.”

Amplifying One Earth's mission, Ridgeway has several conservation projects in the works, including creating new national parks in Chile and Argentina and protecting wildlife and wildlands in Madagascar and Mexico. His memoir, Life Lived Wild: Adventures at the Edge of the Map, spans 50 years of adventuring and conservation.

Advice to activists

As overwhelming as climate change might seem, Ridgeway has spent a lifetime dedicated to nature and is hopeful. He has a tip to share from a good friend, the celebrated conservation biologist George Schaller.