Sierra Madre Del Sur Pine-Oak Forests

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The protection goal is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10.

Bioregion: Mexican Dry & Coniferous Forests (NT28)

Realm: Central America

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

6,131

Ecoregion ID:

558

Conservation Target:

60%

Protection Level:

0

States: Mexico

The short-crested coquette is a colorful species of hummingbird endemic to the Sierra Madre del Sur ecoregion, and one of the rarest in Mexico. They prefer native habitats of cloud and oak-pine forests along the higher elevations of the Sierra Madre, but are also found in shade-grown coffee habitats when this primary habitat is converted. The short-crested coquette is listed as critically endangered due to its extremely small range (about 25 km2) within this ecoregion and a declining population. It is an important pollinator for many flowering plants.

The flagship species of the Sierra Madre Del Sur Pine-Oak Forests ecoregion is the Omilteme cottontail rabbit. Image credit: Creative Commons

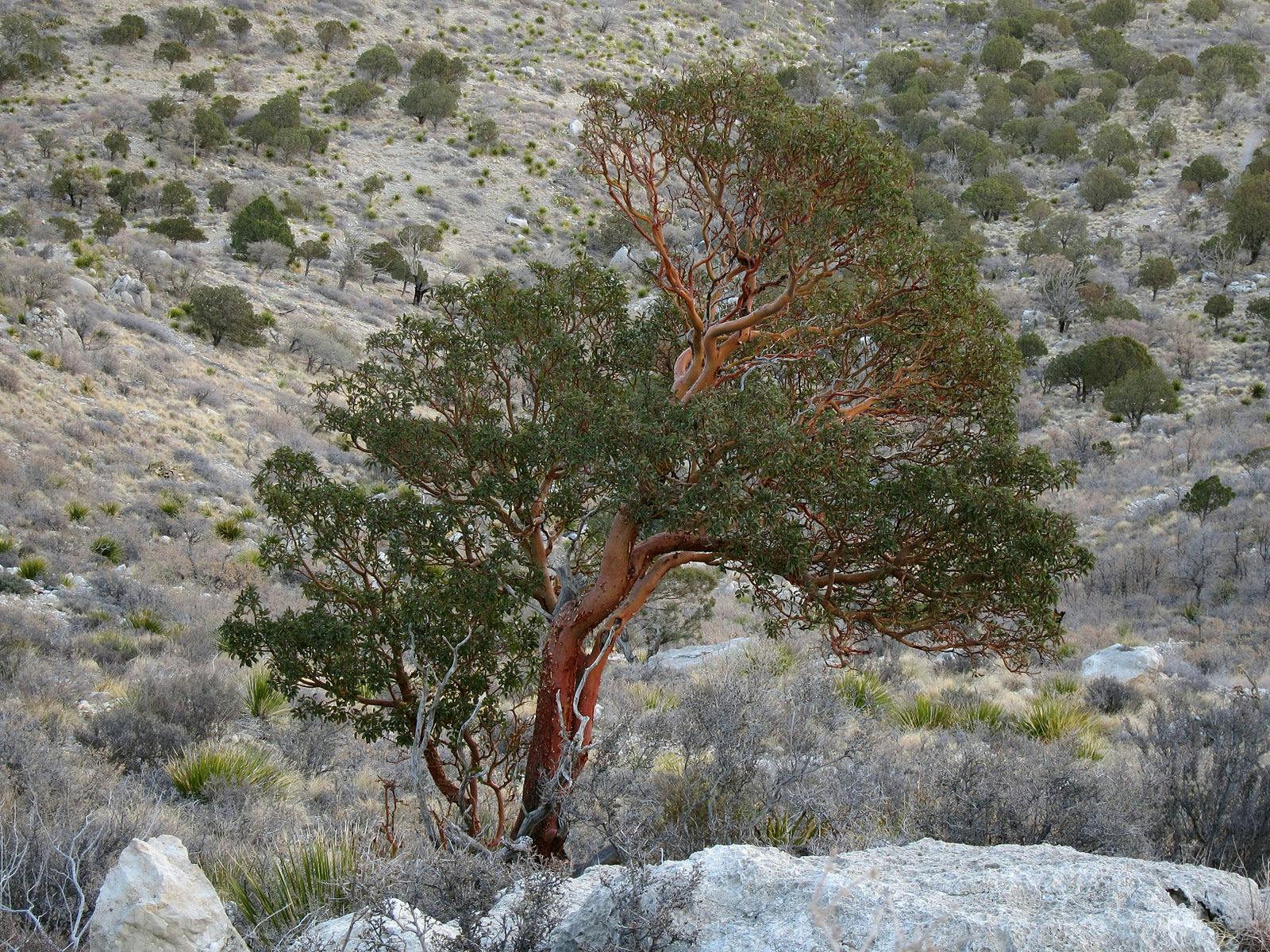

Most of this ecoregion falls within the Guerrero and Oaxaca states. The Sierra Madre del Sur pine-oak forests include various mountain ranges running parallel to the Pacific Coast in a northwest direction. These steep slopes range from 100–3,500m, the climate from temperate to subhumid, and the rainfall from 800–1,600mm/yr. Pine-oak forests of the Sierra Madre del Sur grow on rocky soils of volcanic origin.

There are three main vegetation associations:

- oak forests growing at 1,900–2,500 m, dominated by two species of white oak and Montezuma pine;

- cloud forests at 2,300m with white cedar, Mexican white pine, and a vulnerable species of white oak Quercus uxoris;

- pine-oak forests and some dispersed pine forests at elevations between 2,400–2,500 m characteristically composed of white-oak, naked Indian tree, smooth-bark Mexican pine, and Pringle’s pine.

Isolated from nearby environments due to their altitudinal levels and steep slopes, the temperate forests of the Sierra Madre del Sur ecoregion have recently been considered an unparalleled center of endemism and biodiversity. 48.7% of the species in the state of Guerrero inhabit montane forests, while 43.7% inhabit pine-oak forests. Montane forest coverage plays a crucial role in preventing erosion, primarily in the steep-sloped areas.

There are 595 species of plants, with 7 endemic genera. Although the herpetofauna has not radiated extensively (39 species), half of the amphibians and 34% of the reptiles are endemic. 9% of the 54 species of mammals are endemic including the endangered Omiltemi cottontail rabbit. There are 161 species of butterfly, making it one of the most diverse areas in the Mexican Pacific.

The state of Guerrero has the 4th highest bird richness in the world. In total there are 160 bird species in the ecoregion, with 28 endemics, including the short-crested coquette, white-tailed hummingbird, Oaxaca hummingbird, and white-throated jay.

The states of Guerrero and Oaxaca still have considerable portions of forests in a good state. In recent years proposals to protect more areas within the ecoregion have been gaining traction. Notable formalized protected areas within or touching the ecoregion include Omiltemi State Ecological Park and Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra de Manantlán. Nonetheless, these unique forests are still considered in danger of extinction.

Pinus montezumae. Image credit: Creative Commons

Main threats to this ecoregion are all associated with the removal of vegetation and the subsequent cascade effects. Clearing of forests for large-scale agriculture projects is devastating and threatens this ecoregion with complete destruction. The lower montane forest is being cleared for agricultural use such as growing corn, citrus fruits, and coffee. Cloud forests are also being cleared for coffee plantations and the pine; oak and fir forests are being removed for lumber. One of the after-effects of deforestation is the subsequent invasion by grass, which also affects the distribution and number of mammals. Game hunting affects big and medium-sized mammals, and road expansion makes mammals an easier target for hunters. Conservation actions have been complicated by illegal drug production in the range.

The priority conservation actions for the next decade will be to: 1) incentivize locals to reduce deforestation; 2) encourage sustainable farming practices; and 3) promote educational workshops on the benefits of protecting biodiversity.

Citations

1. Valero, A. Schipper, J. Allnutt, T. 2019. Mexico: States of Guerrero and Oaxaca https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0309 Accessed June 25, 2019.

2. Stattersfield, A.J., M.J. Crosby, A.J. Long, and D.C. Wege. (1998). A global directory of Endemic Bird Areas. BirdLife Conservation Series. BirdLife International, Cambridge, U.K.

3. Diego, N., R.M. Fonseca, F. Lorea, L. Lozada, and L. Monroy. 1997. Canyon of the Zopilote Region Mexico. In S. D. Davis, V. H. Heywood, O. Herrera-MacBryde, J. Villa-Lobos, and A. C. Hamilton (editors), Centres of Plant Diversity: A Guide and Strategy for their Conservation, Vol. 3 The Americas. IUCN, WWF, Oxford, U.K.