Southeast US Conifer Savannas

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The conservation target is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Southeast Savannas & Riparian Forests (NA25)

Realm: Northern America

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

52283

Ecoregion ID:

399

Conservation Target:

12%

Protection Level:

3

States: United States: FL, GA, AL, MS, LA, TN, KY, AR, MO

Stretching from southeastern Louisiana along the Gulf of Mexico coast, northward to extreme southwestern Kentucky, and eastward to Georgia, much of the Southeast US conifer savannas ecoregion was distinguished by vast longleaf pine savannas prior to European settlement. This ecoregion is the biologically richest portion of the North American Coastal Plain, which in 2016 was formally recognized by the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund as the 36th global biodiversity hotspot. Species richness (number of species) and endemism (proportion of species found nowhere else) are particularly high among plants, freshwater fish, amphibians, reptiles, and several invertebrate groups.

The flagship species of the Southeast US Conifer Savannas ecoregion is the longleaf pine. Image credit: Courtesy of US Department of Agriculture, Flickr

This ecoregion, although largely of warm temperate climate, is subtropical in its southernmost portion, including most of Florida. It is the largest conifer-dominated ecoregion east of the Mississippi River. Although this was once considered a forested ecoregion, that idea arose from the mistaken belief that fire was unnatural here, and that in the absence of fire, vegetation would converge on a closed-canopy forest of hardwoods with some pines. Although mixed hardwood forests do occur in this ecoregion, and are very rich in woody species, under a natural fire regime they are largely restricted to naturally fire-protected sites such as steep ravine slopes, islands, and peninsulas. With the highest frequency of lightning strikes in North America north of Mexico, the southern portion of this ecoregion is prone to frequent surface fires that maintain an open savanna condition.

The flagship species, longleaf pine, dominated most of the ecoregion. This long-lived tree depends on frequent fire for its survival. Animals associated with longleaf pine savannas include the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker, the southern fox squirrel, and the gopher tortoise, the burrows of which provide shelter to nearly 400 animal species. This ecoregion also contains the largest native venomous snake in North America, the eastern diamondback rattlesnake, and the largest nonvenomous snake, the eastern indigo snake.

Gopher tortoise. Image credit: Judy Gallagher, Creative Commons

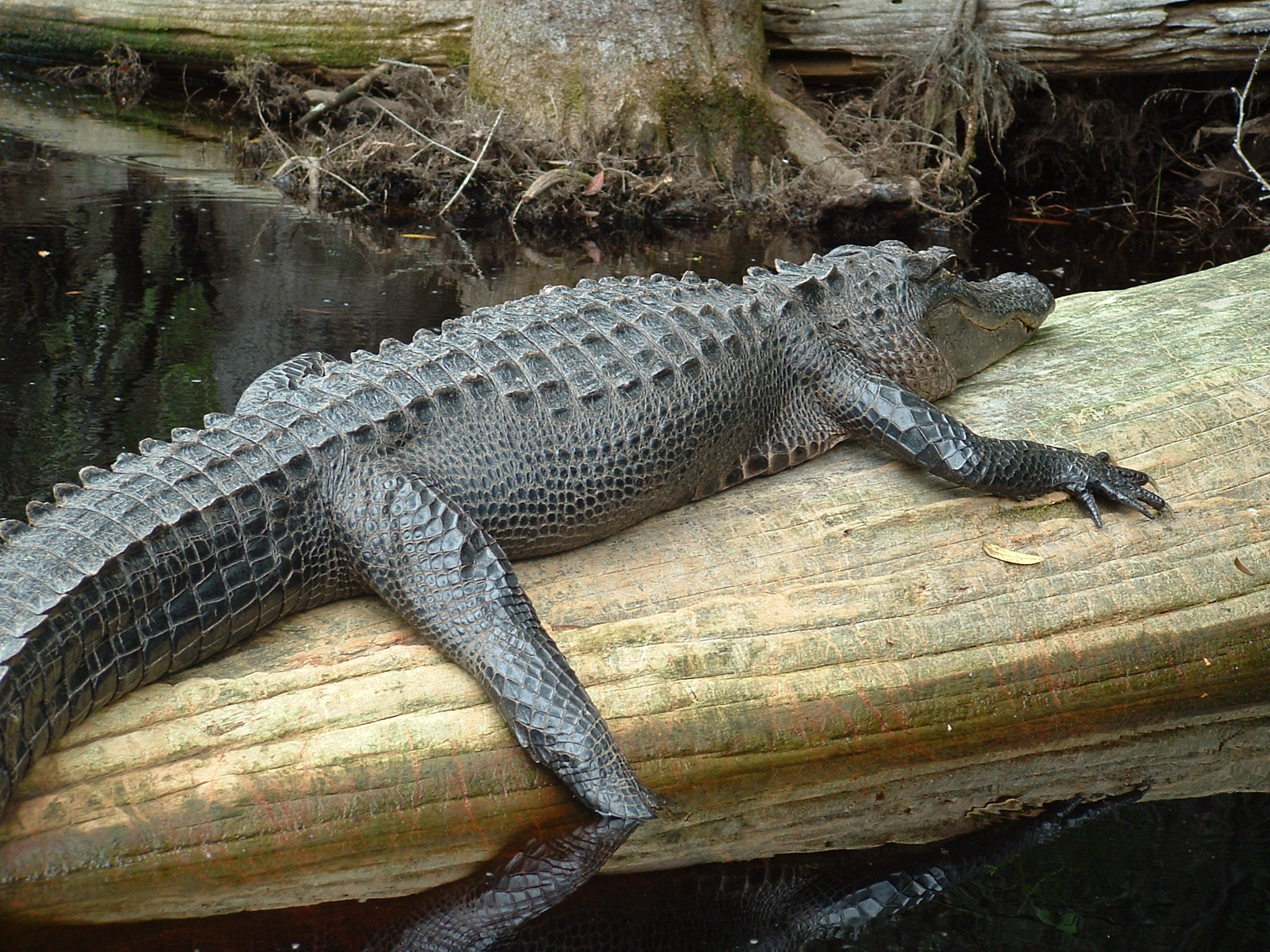

Besides longleaf pine savannas, natural communities include the endemic-rich Florida scrub, the unique seasonally dry prairie of south-central Florida, the Black Belt and Jackson Prairies of Mississippi and Alabama, as well as vast swamps of bald cypress (one of the longest-lived trees in the world) and tupelo along rivers, and many marshes and other wetlands. American alligators, a great diversity of turtles, and river otters are common in aquatic habitats.

The coastal areas, where not overwhelmed by urban development, are especially diverse. Surprisingly, the Big Bend coast of Florida, where the peninsula meets the panhandle, contains the longest undeveloped coastline in the U.S. outside of Alaska. In the northwestern part of this ecoregion (northern MS, western TN, and southwestern KY), longleaf pine drops out and the natural vegetation includes more hardwoods (e.g., oak-hickory) with pines such as shortleaf and loblolly pine, as well as cypress-tupelo swamps along rivers in the loess plains.

Alligator. Image credit: Creative Commons

Across the Coastal Plain as a whole, habitat loss is excessive. A recent study found 86% of the vegetation highly altered or converted, including 73% of forests, 96% of savannas and woodlands, and 98% of grasslands, marshes, and glades. Many species, including endemics found nowhere else in the world, are on the brink of extinction. Human population growth rates are among the highest in the world, leading to massive urbanization and habitat destruction.

Priority conservation actions for the next decade are: 1) improve land use planning and regulations to reduce expansion of human footprint and urban sprawl into natural habitats; 2) greatly increase federal, state, and local acquisition of conservation lands; and 3) improve management of existing conservation lands, especially with respect to management of fire and water.

Citations

1. Noss, R.F., W.J. Platt, B.A. Sorrie, A. S. Weakley, D.B. Means, J. Costanza, and R.K. Peet. 2015. How global biodiversity hotspots may go unrecognized: Lessons from the North American Coastal Plain. Diversity and Distributions 21:236-244.

2. Sorrie, B.A., and A.S. Weakley. 2001. Coastal Plain plant endemics: phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66:50-82.

3. Ricketts, T.H. et al. 1999. Terrestrial Ecoregions of North America: A Conservation Assessment. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=1600)