Food insecurity revives the victory gardens movement

“Grow vitamins at your front door.”

“Every garden a munition plant.”

“Uncle Sam says: garden to cut food costs.”

Thus read advertisements from the U.S. Department of Agriculture encouraging households to join the war effort by growing their own food during World Wars 1 and II. A national provisional gardening movement may be making a comeback, and this time, hopefully for good.

During World War I, a severe food crisis emerged in Europe. As farms became battlefields and farmers were recruited into military service, the burden of feeding millions of starving people fell to the United States. In March of 1917, multi-millionaire Charles Lathrop Pack organized the National War Garden Commission to urge Americans to plant, fertilize, harvest and store their own fruits and vegetables so that more food could be exported to our allies. Citizens were called to utilize all idle land including school and company grounds, parks, backyards, and vacant lots.

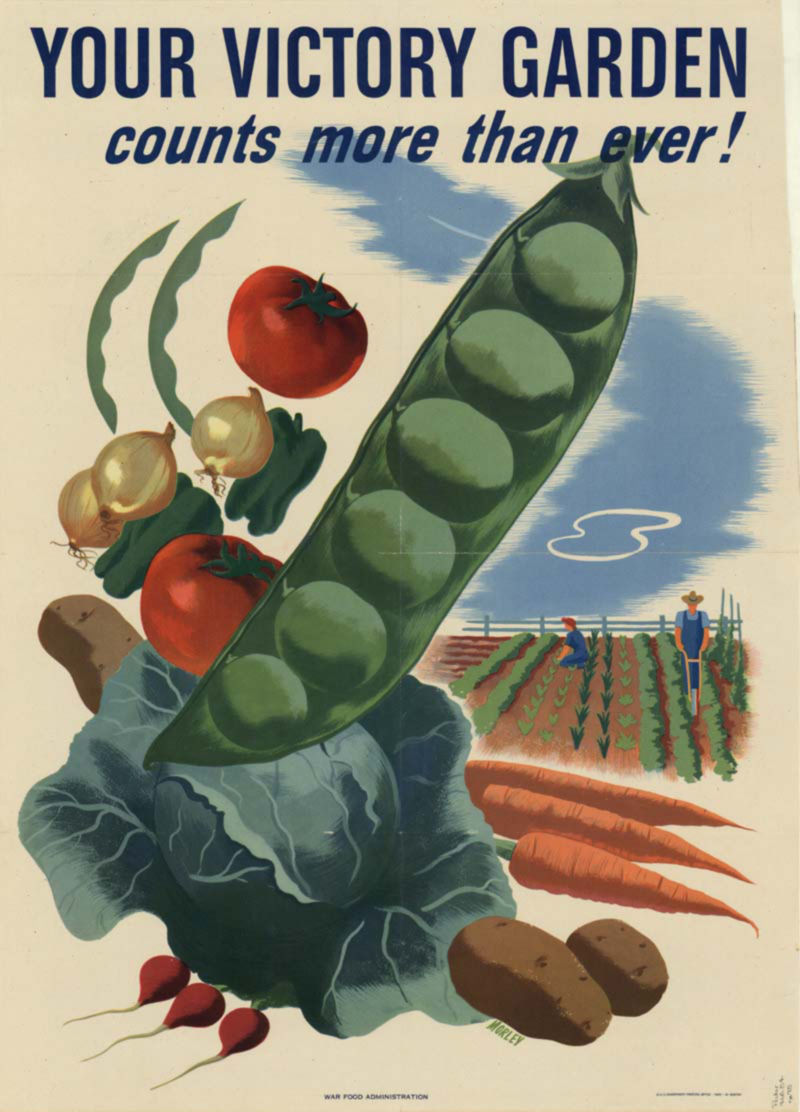

One of many historical Victory Garden advertisements from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Image credit: Creative Commons

The endeavor was so successful that 3 million new garden plots were planted in 1917. Advertisements became urgent: “Prevention of widespread starvation is the peacetime obligation of the United States. … The War Garden of 1918 must become the Victory Garden of 1919.”

When the effort was revitalized during World War II, home, school and community gardeners produced an estimated 40 percent of the country’s fresh vegetables, from about 20 million gardens.

The history of Victory Gardens, like the wars themselves, are not without their shadows, however. Part of the food shortage gap these gardens were intended to fill during World War II had been caused by Japanese Americans farmers being forced off their land and placed in internment camps. Yet, community gardening and farming have also long served as means of survival and independence for marginalized groups.

Leah Penniman, farm manager at Soul Fire Farm in New York and author of “Farming While Black,” spoke about how traditional African-American sustainable farming practices lend themselves to resilience against food insecurity.

However, many Indigenous people have been separated from their land, worsening systemic inequalities, including access to fresh food. Soul Fire Farm has long dedicated itself to working with such disenfranchised communities, but now they are seeing a surge of interest in home food production.

Growing food in your own garden to combat rising concerns of food security is making a resurgence. Image credit: Creative Commons

In recent months, the coronavirus pandemic has led to empty grocery store shelves and a scrambled supply chain. As a result, nurseries — considered essential businesses in some states — have seen a dramatic increase in clientele, and are are quickly adapting to the increased demand as people flock to grow food at home.

As cracks in industrial farming supply chains and practices begin to show themselves, the need for locally-produced food is underscored. Not only do personal and community gardens increase food security for the general public, and help people save money on groceries, they also significantly decrease CO2 levels in the atmosphere, support beneficial insects, pollinators, and birds, and prevent soil erosion. As the benefits of personal gardening are limitless and the disadvantages non-existent, the revived movement toward self-sufficient food security brought on by crisis may bode well for a more sustainable future.

.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=200)