Four Takeaways from November’s New York Times Palm Oil Article

In late November, the New York Times Magazine ran a terrific in-depth feature titled Palm Oil Was Supposed to Help Save the Planet. Instead It Unleashed a Catastrophe, which benefited from a lot of analysis shared by Friends of the Earth and others NGOs. Here are four takeaways from the article.

1. Biofuels are not a climate solution: When biofuels began to be developed at market scale about a decade ago, there was a lot of hope that swapping out fossil fuels for fuels made from plants would provide a silver bullet solution for greening the transportation sector. As Abrahm Lustgarten writes for the Times:

In the mid-2000s, Western nations, led by the United States, began drafting environmental laws that encouraged the use of vegetable oil in fuels. But these laws were based on an incomplete accounting of the true environmental costs. Despite warnings that the policies could have the opposite of their intended effect, they were implemented anyway, producing a calamity with global consequences …

The tropical rain forests of Indonesia, and in particular the peatland regions of Borneo, have large amounts of carbon trapped within their trees and soil. Slashing and burning the forests for oil-palm cultivation had a perverse effect: It released more carbon. A lot more carbon.

That’s why Friends of the Earth opposed the Renewable Fuel Standard back on 2008, and why we continue to reject large-scale biofuels, even as we fight to ramp down fossil fuel production. Like a lot of techno-fixes, swapping fossil fuels for plant-based fuels is merely shuffling deck chairs on the Titanic. To reverse the momentum that has devastated the world’s climate, the first and best thing to do, is for the world’s elites and middle classes to decrease consumption.

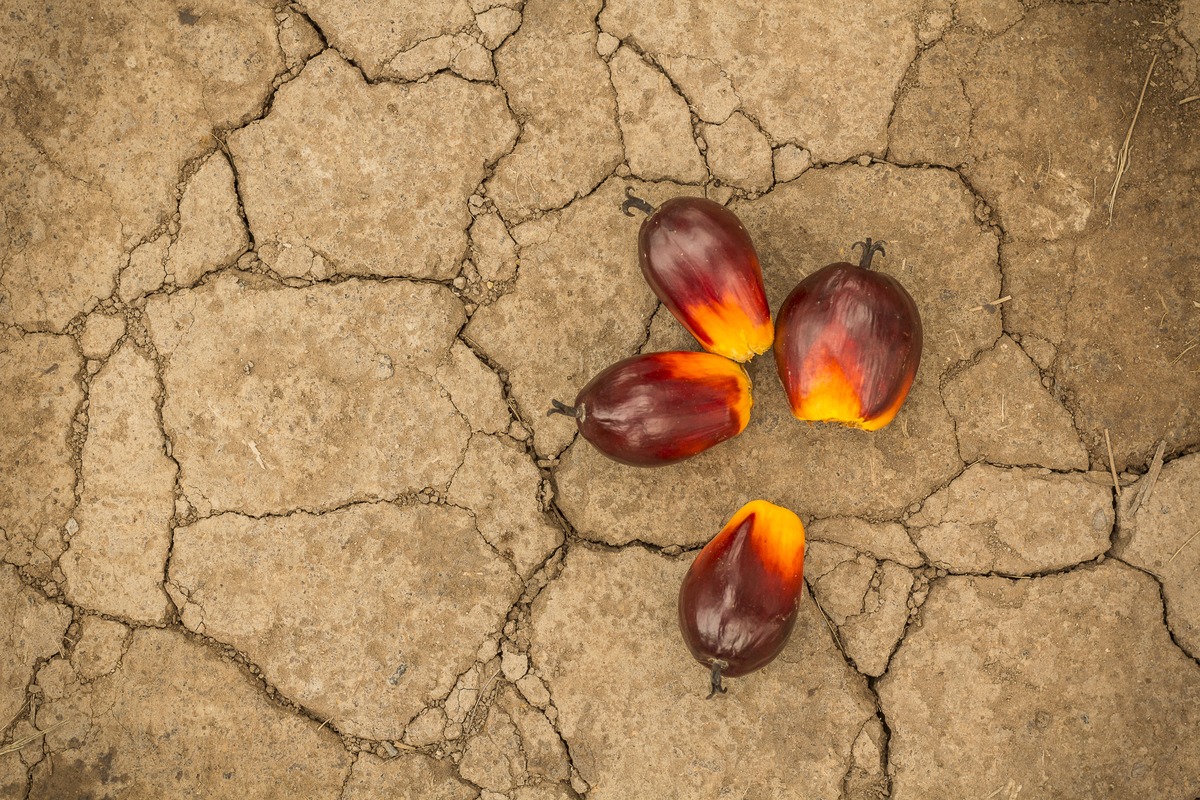

Victor Barro/Friends of the Earth Spain

2. The palm oil boom has spurred economic growth…mostly for the super-rich and the corporate class: One of the arguments for ongoing expansion of the palm oil industry is that, like all extractive industries, palm oil brings economic growth. Lustgarten writes, “When the large companies began to expand their timber and palm-planting to Kalimantan, they brought roads, construction and an influx of goods. They also offered jobs.” But at the same time, “The unprecedented palm-oil boom, meanwhile, has enriched and emboldened many of the region’s largest corporations, which have begun using their newfound power and wealth to suppress critics, abuse workers and acquire more land to produce oil.”

Indeed, 14 of Indonesia’s 32 billionaires made their billions from palm oil.

You can’t generate this much wealth without causing irreparable damage to ecosystems: “As the money flowed, so did the development. From 2007 to 2014, palm concessions in Kalimantan more than tripled. … Across Indonesia, trees were cut down at a rate of three acres every minute to make room. Soon, palm plantations extended … in every direction.”

Victor Barro/Friends of the Earth Spain

3. The palm oil industry is built on corruption and violence against land defenders: Lustgarten writes:

In 2014, Indonesia’s highest judge and three associates were convicted in a huge bribery scandal … linked to palm land deals in Borneo. Stories of corruption, and threats to keep it quiet, were legion. Global Witness has counted at least eight assassinations of Indonesian environmentalists fighting palm oil.

As Friends of the Earth International recently pointed out, even palm oil certified as “sustainable” by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is generated by a system that has violence at its core. This point is underlined in the Times article by my colleague Zenzi Suhadi, of Walhi when he says, “It’s all a deception. There is no sustainability.”

This is a discouraging sentiment. But these comments reflect an imperative to orient toward a development model predicated not on large-scale extraction for global markets, but on agroecology and agroforestry — both of which depend on securing the rights of indigenous peoples to manage their own lands and forests.

Victor Barro/Friends of the Earth Spain

4. U.S. policies and U.S. financing are at the heart of the problem: Lustgarten writes: “I asked how important the American biofuels mandate has been, given that other countries buy more Indonesian palm oil than Americans do. The answer was unequivocal: It’s what got Indonesian palm off the ground.”

Of course, it’s not only U.S. and EU biofuel policies that have driven the palm oil boom. It’s also the flood of private investment that followed the initial biofuel policy mandates — investments from Malaysian and Indonesian banks as well as Wall Street firms and even, most likely, your own pension fund.

As Lustgarten reports, when Friends of the Earth brought Zenzi Suhadi from Indonesia to Washington to talk to the Senate earlier this year, his message was clear: the palm trade, driven by American investment, is slowly killing his country. “It’s important for you to understand that all acts of deforestation in Indonesia start with a signature,” he said. “And more than a little of it starts right here.”

If we’re going to turn around the deforestation crisis and its huge contribution to the climate crisis, we need to fundamentally transform capitalism. One way to get a grip on this is to shift the practices of the largest investment firms – the likes of Vanguard and BlackRock, which manage assets in the trillions and have millions of clients worldwide. Despite increasingly loud lip service to sustainability, BlackRock is the largest U.S. investor in the palm oil sector, and the largest investor in climate destruction on earth. That’s why we need to tackle BlackRock’s Big Problem — deep investments in both fossil fuels and deforestation — head-on.

Ultimately, the best way for us in the U.S. to do our part is to ramp down our energy use, reduce our consumption of luxury goods — including the junk food and cosmetics that use the bulk of palm oil in the U.S. market — and to defund deforestation and shift financing to support rights-based economic alternatives for forest-dependent communities.

Victor Barro/Friends of the Earth Spain