How Belize saved its coral reefs

- Nature Conservation

- Ocean Conservation

- Coral

- Ecosystem Restoration

- Blue Carbon

- Mangroves

- Central America Realm

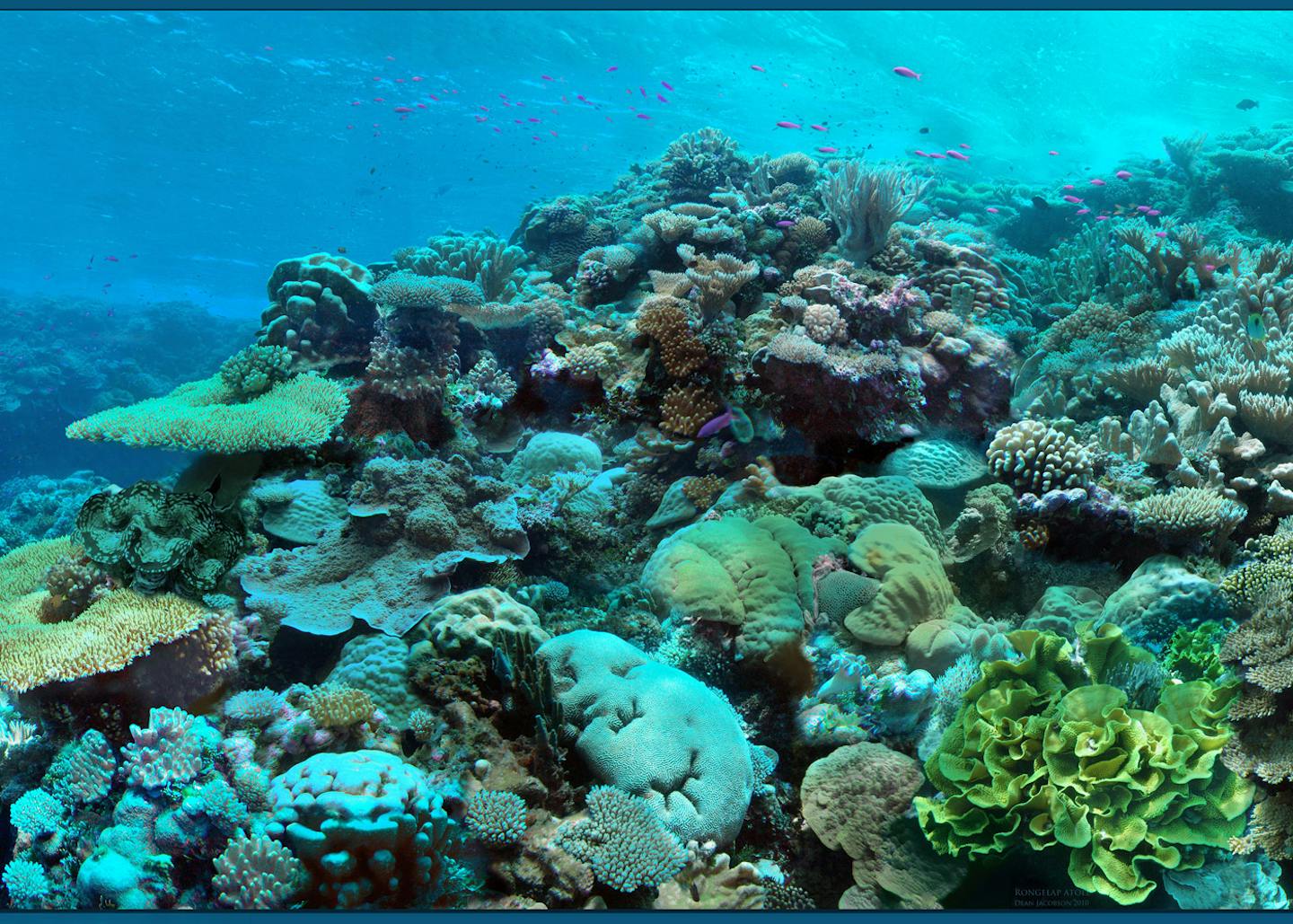

Coral reefs are one of the most biodiverse systems on the planet, providing food and shelter to nearly a quarter of all marine species, with an estimated millions more as-yet undiscovered organisms living in and around reefs. Reefs also support the livelihoods of up to six million fishers around the world, buffer coastal communities from the most destructive waves in tropical storms, and serve an important role in tourism and local economy.

But global reef systems have been decimated by climate change, oil exploration, and coastal development. Coral is exceptionally vulnerable to rising ocean temperatures and increased ocean acidification, both products of climate change, which can lead to mass bleaching events – the Caribbean alone has lost up to 80% of its coral in recent decades.

Southern Belize’s mangrove forests, which hold the soil together and prevent coastal erosion and sediment from falling into the sea, were depleted by Hurricane Iris in 2001, and the resulting erosion harmed the nation’s coral reefs, which require clean, clear waters to survive. Mangrove forest clearing for coastal development also had a devastating effect, and a lack of government oversight or a plan for conservation exacerbated the problem.

Lisa Carne, a marine biologist, saw firsthand the damage after Hurricane Iris to Laughing Bird Caye.

The devastation made Carne wonder if reseeding and replanting coral beds the same way landscapers replenish flower beds could help the reef recover. She set out to answer her question and founded Fragments of Hope, a nonprofit dedicated to developing and maintaining coral nurseries at Laughing Bird Caye and other sites in Belize.

The first of their kind in Belize, these nurseries brought the reefs at Laughing Bird Caye back from the brink of extinction with over 49,000 nursery-grown coral fragments replenished. Just as importantly, Fragments of Hope also spread public awareness of the problem and facilitated buy-in from local communities. Their work and outreach also persuaded the government of Belize to reprioritize the reef.

In a 2012 public referendum, 96% of voters supported the restoration and protection of reef systems. With UNESCO’s help, the government began to work with scientists and grassroots and environmental organizations to tighten regulations, preserve mangrove habitats, and enact more oversight of reef systems.

Belize’s government implemented a long-term conservation plan in 2015, and in 2017 it put a moratorium on all oil exploration. In 2018 UNESCO removed Belize from its List of World Heritage in Danger.

The success demonstrates how methodical and consistent restorative processes can help even severely-damaged coral recover. Perhaps even more significantly, the multilateral conservation plan modeled how grassroots environmental movements can incite governments — even of small countries with limited budgets — to enact bold and innovative environmental laws and regulations.

.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=200)