One Earth's Karl Burkart in conversation with Matthew Monahan

One Earth's co-founder and Deputy Director, Karl Burkart, joined Matthew Monahan on Ma Earth's podcast, The Regeneration Will Be Funded, to discuss imperatives for Nature and One Earth's work in developing climate and nature models.

Watch the full interview:

Abridged transcript below.

Introduction and Overview

Matthew Monahan: Welcome to The Regeneration Will Be Funded. This is a show about regenerative finance and pathways to a life-affirming economy. I'm your host, Matthew Monahan. Today, I’m joined by Karl Burkart, co-founder and deputy director of One Earth. People may remember we had Justin Winters, co-founder of One Earth, on in Season 1.

It’s a pleasure to welcome you during New York Climate Week 2024. Thanks for being here, Karl.

Karl Burkart: Thanks for having me. Very excited.

Matthew Monahan: Awesome. So, Climate Week—how many of these have you done? What are you noticing this year?

Karl Burkart: I think I’ve done 10. It’s not really just “Climate Week” anymore; it’s “Climate and Nature Week.” There’s also a bit of regenerative agriculture mixed in, though we’re not quite there yet. For me, it’s tricky because I manage science and strategic impact at One Earth, which involves a broad range of work. We’re most known for the One Earth Climate Model, so I’m constantly switching between climate energy transition discussions and nature finance or data spaces.

At One Earth, we realized early on that we needed to look at climate and nature together. This makes Climate Week exhausting but also rewarding. It’s exciting to see concepts we’ve used for years being adopted by bankers and others on Wall Street. It feels like some of these ideas are finally becoming mainstream.

Karl Burkart at the Climate and Capital Conference during Climate Week 2024.

Observations on collaboration and carbon markets

Matthew Monahan: Do you feel like we’re all rowing in the same direction? What are your observations about how the space is maturing?

Karl Burkart: It’s a flotilla, not a unified effort. There’s so much ground to cover, so it’s hard for everyone to row together. That said, there are a lot of conversations happening, especially around carbon markets, which bridge the climate and nature agendas.

I’ve avoided this topic in the past, but I spent time at Climate Week exploring how Deloitte, PwC, and Accenture are positioning themselves. The big challenge is that our global operating system isn’t valued in economic terms. The $100 trillion GDP depends on this “machine” that provides water, carbon dioxide removal, and other essentials, but those dependencies aren’t priced into the global economy.

Carbon markets were an early attempt to address this, but the voluntary nature-based carbon market collapsed due to numerous problems. This week, there were announcements aimed at rebooting the REDD+ market (reduced emissions from deforestation and degradation) with agreements involving Amazonian tribes. Initiatives like these are crucial because we need large-scale land restoration to absorb historic carbon emissions. However, the current market for nature-based carbon credits is struggling—valued at just $0.28 per ton in some cases.

New pieces are coming together, like credit rating systems for carbon markets, but we’re still far from where we need to be. Watching these developments is both fascinating and a bit unsettling, especially seeing how bankers are now engaging seriously with these issues.

.jpg)

One Earth logo over GSN sphere.

Communicating climate risks and solutions

Matthew Monahan: I find it inspiring to see people engaging seriously, but I worry about the incentive structures underpinning this. People and organizations change, but the machinery of capitalism often doesn’t. What’s your take?

Karl Burkart: I agree. While it’s inspiring to see individuals taking this seriously, the system itself doesn’t fully grasp how nature underpins our survival. For instance, nature absorbs half of our carbon emissions annually without any intervention, but models show this capacity is in decline. As we approach tipping points like AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) and permafrost thawing, the assumption that nature will keep functioning as it does becomes untenable.

Most climate models assume a constant backdrop of functioning carbon sinks, but that’s not guaranteed. Back in 2017, when we were forming One Earth’s science program, almost no one was modeling how warming affects these sinks. We’ve integrated this into the One Earth Climate Model, which shows nature’s carbon uptake is far from a given.

Insurance companies are starting to take these risks seriously, but even explaining this concept to others often results in puzzled looks. Many decision-makers lack ecological literacy. It’s not just about modeling risk but also communicating these challenges in a way that motivates action.

Matthew Monahan: That touches on an important tension. The climate movement often emphasizes certainty—99% of scientists agree—but we know there’s immense uncertainty in dynamic systems. How do you balance communicating urgency while acknowledging the complexities?

Karl Burkart: It’s a tricky balance. At the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, where our team managed an audience of 80 million people, we noticed how doom-and-gloom messaging backfired. Younger audiences expressed hopelessness, with some even sharing suicidal thoughts. We were unintentionally manufacturing despair.

Doom-and-gloom narratives have dominated climate communications for years, driven by the idea that fear motivates action. However, One Earth was founded on a different premise: people need a vision of the future they can work toward. We decided to focus on constructive solutions and pathways to a better world. This approach initially faced criticism from major NGOs, but we believed it was necessary to keep people engaged and mentally well.

One Earth's three pillars of climate action.

One Earth’s climate model and three-pillar framework

Matthew Monahan: Over the years, One Earth has focused on a three-pillar solution framework: renewable energy transition, land conservation, and regenerative agriculture. Is that still how you approach the problem?

Karl Burkart: Absolutely. I’m particularly proud of the One Earth Climate Model. We were early funders of research at Stanford that advocated for 100% renewable energy—a controversial stance at the time. But as we delved deeper, we realized an all-electric future wasn’t feasible or equitable. Critical minerals and just-transition challenges revealed that a diverse energy mix is essential.

Our climate model incorporates three components: energy transition, nature conservation and restoration, and food security. The energy model shows 69% electrification is achievable, with the rest coming from diverse renewable modalities. Beyond that, we need massive land restoration—about 350 million hectares of degraded land—to absorb legacy carbon emissions.

The three pillars—energy, nature, and food—are interconnected. Each has subsets, like conservation and restoration under nature, and specific agricultural solutions like soil carbon farming. Our Solutions Framework now includes 70+ detailed pathways, each playing a unique role in this global transition.

Matthew Monahan: Could you give examples of these solutions?

Karl Burkart: Sure. Under energy, there are four subsections: power, heat, mobility, and efficiency. For example, wind turbines fall under power, while efficiency solutions are often overlooked but vital. Under nature, we focus on conservation—protecting what exists—and restoration, which involves reclaiming degraded land without displacing communities. Regenerative agriculture is another key area, turning farms into carbon sinks instead of sources.

Each solution has a specific role. For example, soil carbon farming sequesters carbon while improving soil health. These are practical steps that help build resilience and restore balance.

One Earth's knowledge partners.

Building expertise and driving impact

Matthew Monahan: Modeling and prescribing solutions is a massive undertaking. Who are you collaborating with, and how are you coordinating all this expertise?

Karl Burkart: From the start, we built a strong bench of scientists—mostly practicing academics rather than NGOs. These scientists are at the forefront of their fields, and many have gained the freedom to pursue independent, cutting-edge research. To date, we’ve published 40 peer-reviewed and technical papers since launching in 2018.

One recent example is our work mapping mature and old-growth forests in the US—a first of its kind. We collaborated with regional scientists to create a peer-reviewed paper that provides a comprehensive map of these forests. Projects like this are foundational for creating a global blueprint for conservation and restoration.

Matthew Monahan: Why focus so much on science and research? Is it to inform policy, private sector decisions, or funders?

Karl Burkart: Initially, the focus on rigorous science came from our audience. One Earth’s co-founder, being a high-profile individual, required a strong foundation of credibility for the bold ideas we were proposing. At the time, concepts like 1.5°C targets and net-zero emissions were far from settled.

The second reason was asset allocation. Foundations often make funding decisions based on relationships or trends rather than clear data. We wanted to create a methodology informed by science to guide investments—identifying the most critical bioregions, prioritizing conservation areas, and supporting underfunded communities. This ensures funding goes to the right places without causing harm.

Matthew Monahan: How are these models being used now?

Karl Burkart: They’ve evolved significantly. For example, the Global Safety Net and One Earth Climate Model have been widely adopted by asset managers and governments. The Global Safety Net, which outlines land-use priorities, is particularly valuable for informing biodiversity conventions. Surprisingly, it has also gained traction in capital markets, showing a broad range of applications for these tools.

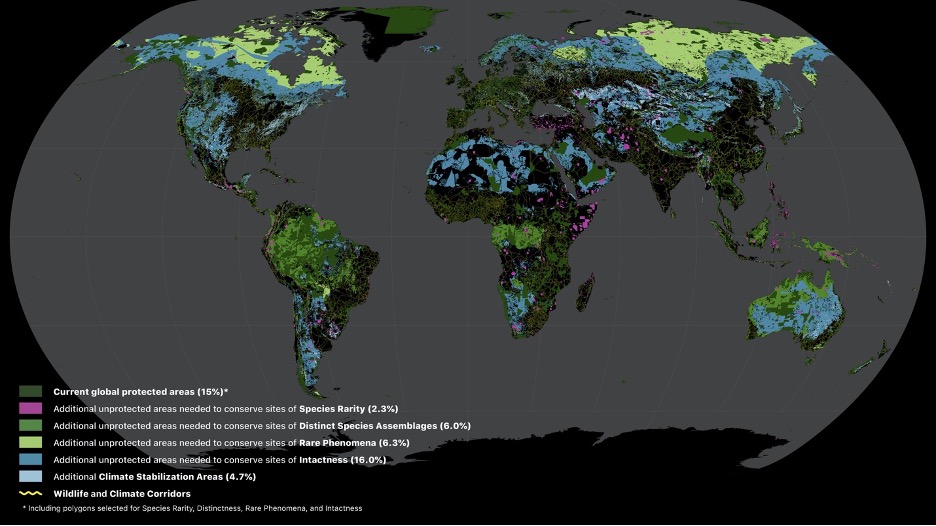

Close-up of the Global Safety Net.

The Global Safety Net and conservation priorities

Matthew Monahan: Can you elaborate on the Global Safety Net model? What is it, and what does it aim to achieve?

Karl Burkart: The Global Safety Net is the second major model under our Nature pillar. It’s a collaboration of scientists, initially inspired by the energy model framework. The first paper, The Global Deal for Nature, introduced the idea of conserving 30% of lands and oceans by 2030 (30x30). Our research showed that 30x30 is just a stepping stone; we actually need to protect about 50% of the planet.

The Global Safety Net compiles 16 other models and identifies six types of conservation areas. It maps biologically important land globally, offering detailed spatial analyses that highlight high-priority areas for conservation. These maps are used to guide governments and organizations on where to focus their efforts.

Matthew Monahan: What’s the headline about the most urgent conservation areas?

Karl Burkart: The Conservation Imperatives layer of the Global Safety Net highlights 1% of land that harbors rare and threatened species. This magenta-colored layer shows the last remaining fragments of critical habitat that need immediate protection to prevent extinction.

In total, we identified 4,000 key sites globally, equivalent to about 1% of land. This doesn’t mean we only need to protect 1%—we need to protect 50% overall. But this magenta layer represents the “tip of the spear,” areas that need urgent action in the next 3–5 years. We also calculated the costs of land acquisition and conservation for these sites, which is critical for driving investment.

Matthew Monahan: What impact has this had?

Karl Burkart: It’s been transformative. For example, the Global Safety Net Index ranks countries based on their conservation performance, which has created accountability. Countries now see how well they’re protecting biologically important land compared to others. This kind of transparency is common in climate reporting but was missing for biodiversity.

The model is also being adopted by asset managers and governments. We’ve had ministry officials and policymakers from over 190 countries access the platform. The widespread use and integration of this model show how science-driven tools can guide global priorities.

The Global Safety Net layers.

Indigenous stewardship and conservation financing

Matthew Monahan: Indigenous stewardship plays a huge role in conservation. How does that factor into the Global Safety Net?

Karl Burkart: Indigenous territories are crucial. Our research found that 37% of all biologically important land is already protected by Indigenous people, often overlapping with formal protected areas. When combined with the existing 17% of officially protected land, we’re already over 30% protected globally—around 33–35%.

However, Indigenous communities receive little to no funding to support their conservation efforts. For example, Indigenous groups in the Amazon and Ecuador manage some of the most biodiverse areas on Earth with no financial support, despite enormous pressures from deforestation. These communities are doing a phenomenal job, yet they’re excluded from conservation financing discussions.

Our view is that Indigenous lands should be automatically grandfathered into conservation targets, and these communities should receive funding to continue their stewardship. They’ve been protecting these areas for thousands of years, and financing their efforts is one of the most critical interventions we can make.

Matthew Monahan: What about financing mechanisms? How do we direct funding to these high-priority areas?

Karl Burkart: Financing is a significant challenge. Protecting and managing the Global Safety Net requires about $666 billion annually. Current mechanisms, like carbon credits, may contribute a fraction of this—perhaps $50 billion if optimized—but we need innovative solutions to close the gap.

One promising approach is bioregional financing facilities. These facilities would allocate funds directly to bioregions based on ecological need. A global system could distribute resources efficiently, targeting areas with the highest conservation priorities. For example, a global “Earth fee” or a one-basis-point tax on financial transactions could generate massive funding streams.

Aggregating capital at the bioregional level could also help fund grassroots organizations, which often struggle to access large-scale financing. There are thousands of small, high-impact projects worldwide, but they’re overlooked by big foundations that prefer large deals. Bioregional facilities could bridge this gap and ensure that resources reach the people and communities on the ground.

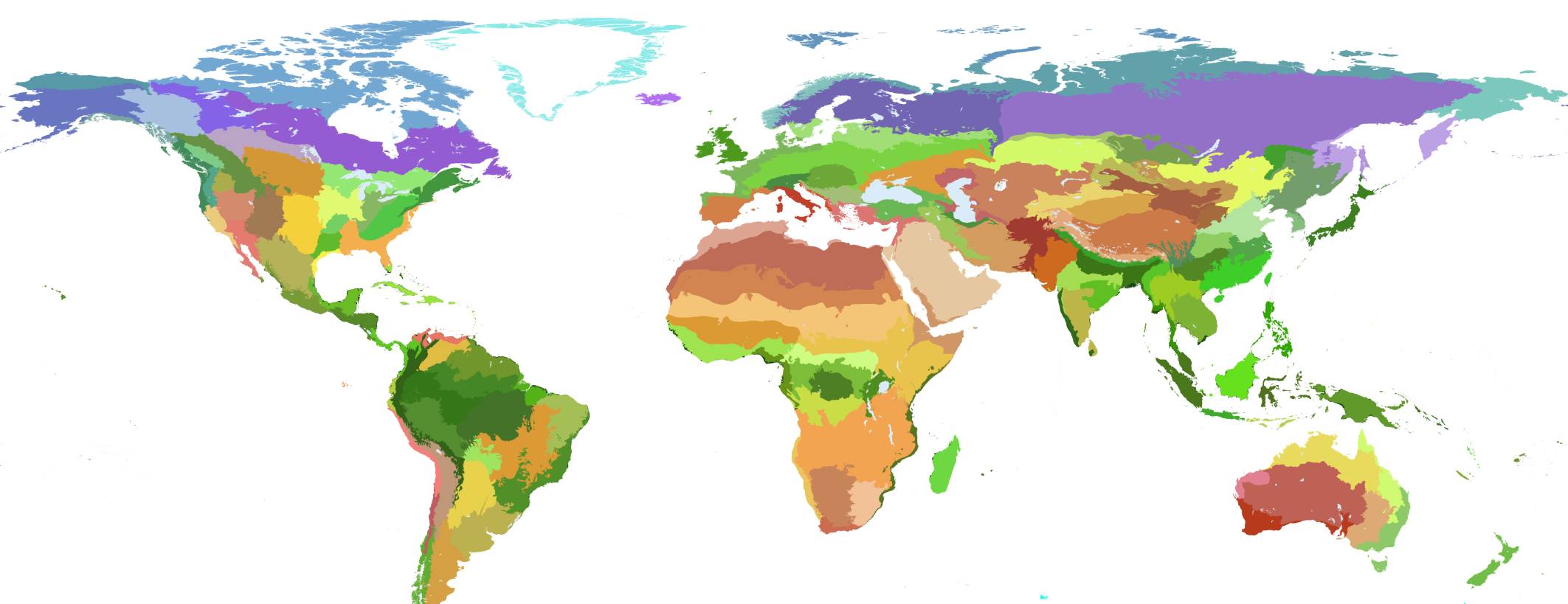

Bioregions of the Earth. Image Credit: Karl Burkart, One Earth.

Bioregions and their role in conservation

Matthew Monahan: One Earth has been a leader in bioregional thinking. Can you explain the work you’ve done on bioregions and why they’re important?

Karl Burkart: The concept of bioregions emerged from the realization that nature doesn’t adhere to political boundaries. Instead, ecosystems are defined by climatic, hydrological, and topographical features. For example, a single ecoregion might span multiple countries. To effectively manage conservation, we need to look at the world through nature’s lens, not arbitrary borders.

Using data science, we grouped 844 terrestrial ecoregions into 185 bioregions. These are relatively uniform areas that reflect natural boundaries rather than political ones. This approach allows us to track progress toward conservation goals in a way that aligns with ecological realities.

Matthew Monahan: How does this integrate with marine ecosystems?

Karl Burkart: Initially, we focused on terrestrial bioregions, but Justin, my co-founder, pointed out the importance of connecting adjacent marine ecosystems. We incorporated marine ecoregions into the framework, creating a seamless transition between land and ocean. While the integration can be complex, it reflects the interconnectedness of ecosystems.

Matthew Monahan: Some argue that drawing boundaries, even for bioregions, is problematic since nature is fluid and doesn’t have hard lines. How do you respond to that?

Karl Burkart: It’s a valid critique. Nature is dynamic, and hard lines can oversimplify complex systems. However, from a practical standpoint, precise boundaries are necessary for tracking progress and allocating resources. For example, if you’re setting targets for protecting parts of the Amazon, you need clearly delineated areas to measure success.

We used bioregions as a layer on top of the Global Safety Net to track ecological representation, a key principle in the UN’s Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. While the boundaries may not be perfect, they help create a framework for accountability and action.

Matthew Monahan: What role do bioregions play in conservation financing?

Karl Burkart: Bioregions provide a structure for directing funds where they’re needed most. For instance, if we had a global funding mechanism based on ecological need, bioregional financing facilities could ensure that resources flow to the right places. These facilities could aggregate capital, making it easier to fund grassroots organizations and smaller-scale projects that often get overlooked.

The key is ensuring that the money moves into the bioregion itself, supporting both ecological restoration and the communities that depend on these ecosystems.

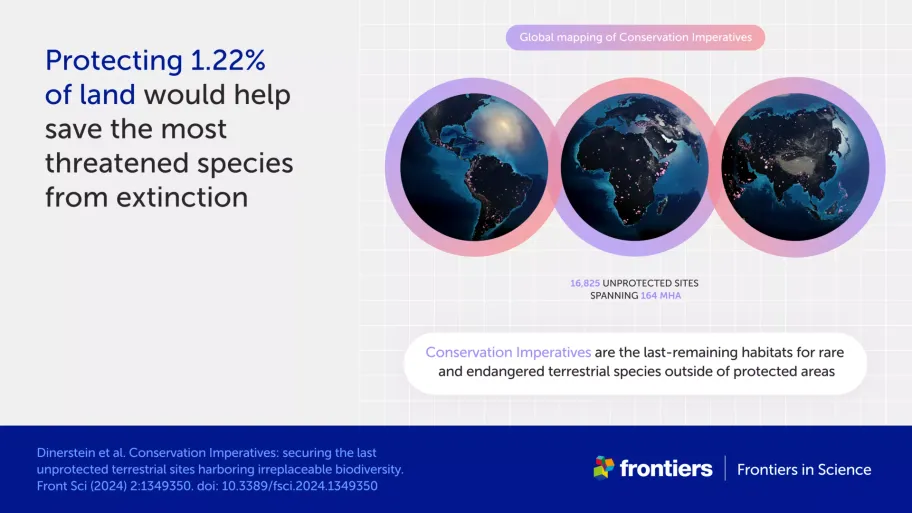

Conservation Imperatives infographic via Frontiers.

Conservation imperatives and urgent action

Matthew Monahan: One of your recent papers focused on Conservation Imperatives. Can you share more about it?

Karl Burkart: The Conservation Imperatives paper is a detailed analysis of the most critical habitats for preventing extinctions. It builds on the Global Safety Net and focuses on the magenta-colored areas on the map—what we call "last-remaining fragments of habitat." These areas harbor rare and threatened species and represent the front lines of the extinction crisis.

We identified 4,000 key sites globally, which are home to some of the most biodiverse and ecologically important ecosystems. Altogether, these sites cover about 1% of the planet’s land area. Alarmingly, we found that half of these areas are already degraded or lost to activities like agriculture and deforestation. The paper emphasizes the urgent need to protect and restore these areas to reverse the extinction crisis.

Matthew Monahan: What’s the timeline for action on these sites?

Karl Burkart: We recommend immediate action within the next 3–5 years. The paper also estimates the costs of conservation, including land acquisition and management. These investments are critical for ensuring these habitats remain viable for the species that depend on them.

Matthew Monahan: How has this research been received?

Karl Burkart: It’s been impactful. For example, Frontiers in Science selected the paper as one of 20 featured publications this year. It’s also generating significant interest ahead of the upcoming biodiversity convention in Colombia. The findings highlight the need for more targeted conservation efforts, particularly in areas that are unprotected yet biologically essential.

This paper is part of a broader push to refine our understanding of conservation priorities. It’s not just about how much land we protect but ensuring that we’re protecting the right places.

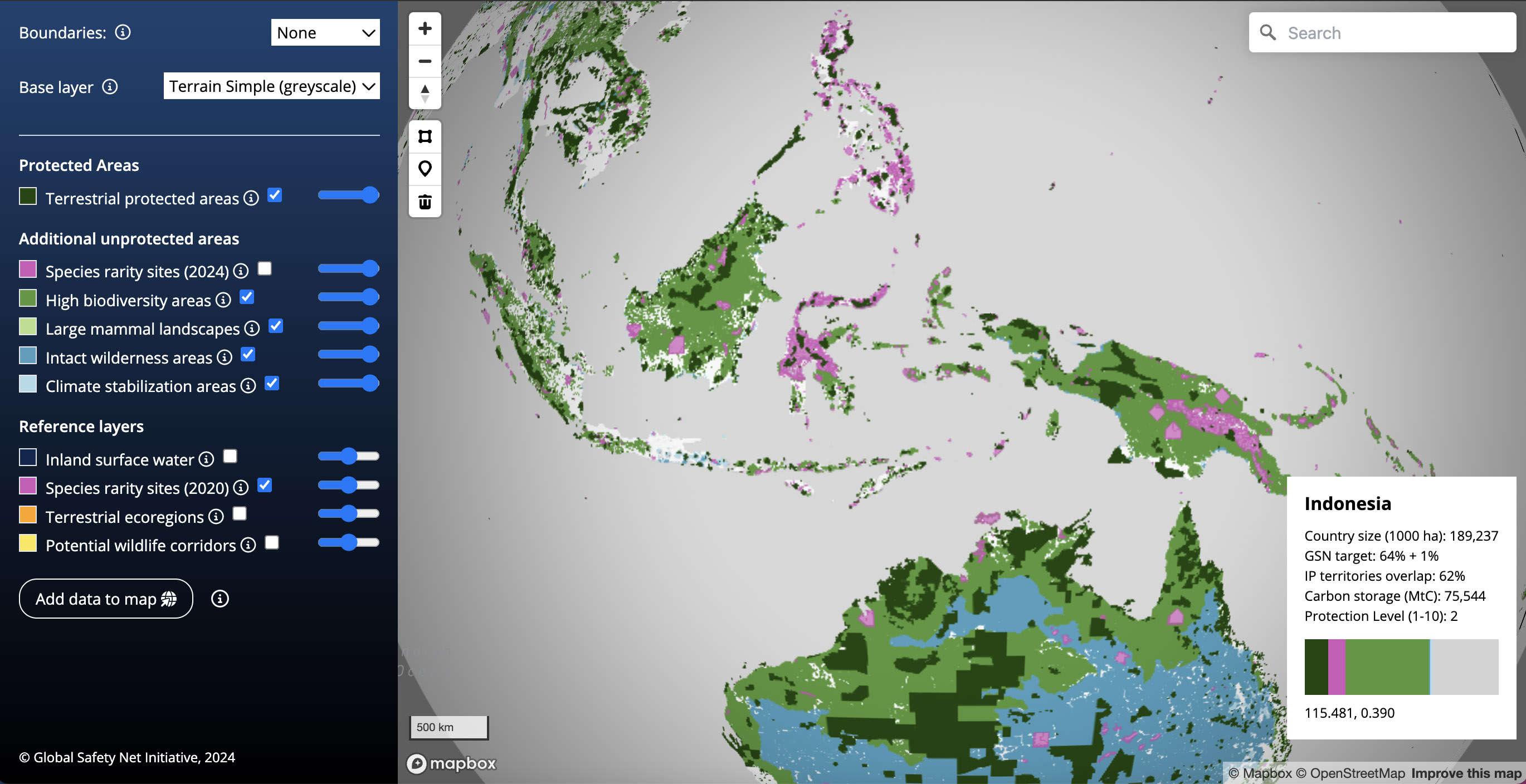

The Global Safety Net map viewer, showing rare species areas across Indonesia.

Bridging funding gaps for conservation

Matthew Monahan: How do you see your solutions framework and models helping funders and decision-makers navigate the conservation space?

Karl Burkart: Our solutions framework and models provide clarity in a complex space. For example, the Global Safety Net and the Conservation Imperatives map offer funders and policymakers a clear starting point—specific sites, solutions, and priorities to focus on.

We’ve seen funders express interest in climate philanthropy but often feel overwhelmed by the complexity. Many are new to the space and don’t know where to begin. Our tools break things down into actionable categories: energy, nature, and food, with 70+ specific solutions under them. This helps funders align their investments with high-priority areas and underfunded solutions.

Matthew Monahan: Can you talk more about the gaps in funding, especially for nature?

Karl Burkart: The funding disparity is stark. Renewable energy and technology receive significant investment, but nature often gets overlooked. For example, regenerative agriculture is gaining traction in impact investing, but conservation—especially protecting ecosystems—still struggles to attract funding. Nature’s “outputs,” like oxygen and biodiversity, aren’t commodities you can trade, making it harder to build financial support.

This is why we’re excited about tools like the Climate Solutions Opportunity Map, which integrates data from private and philanthropic investments. By mapping deal flows across the 70+ solutions, we can identify overfunded areas and highlight underfunded opportunities. This kind of analysis helps direct resources where they’re most needed.

Matthew Monahan: What role do bioregional financing facilities play in closing these gaps?

Karl Burkart: Bioregional financing facilities are essential for bridging the gap. They allow us to aggregate funding at the bioregional level and direct it to projects based on ecological need. For example, grassroots organizations often manage critical conservation projects but struggle to access large-scale funding. By using bioregional facilities, we can streamline resources and support smaller, high-impact initiatives.

Scaling this approach requires global cooperation and innovative mechanisms like an “Earth fee” or a financial transaction tax. These could generate substantial funding streams to support the $666 billion needed annually for global conservation efforts.

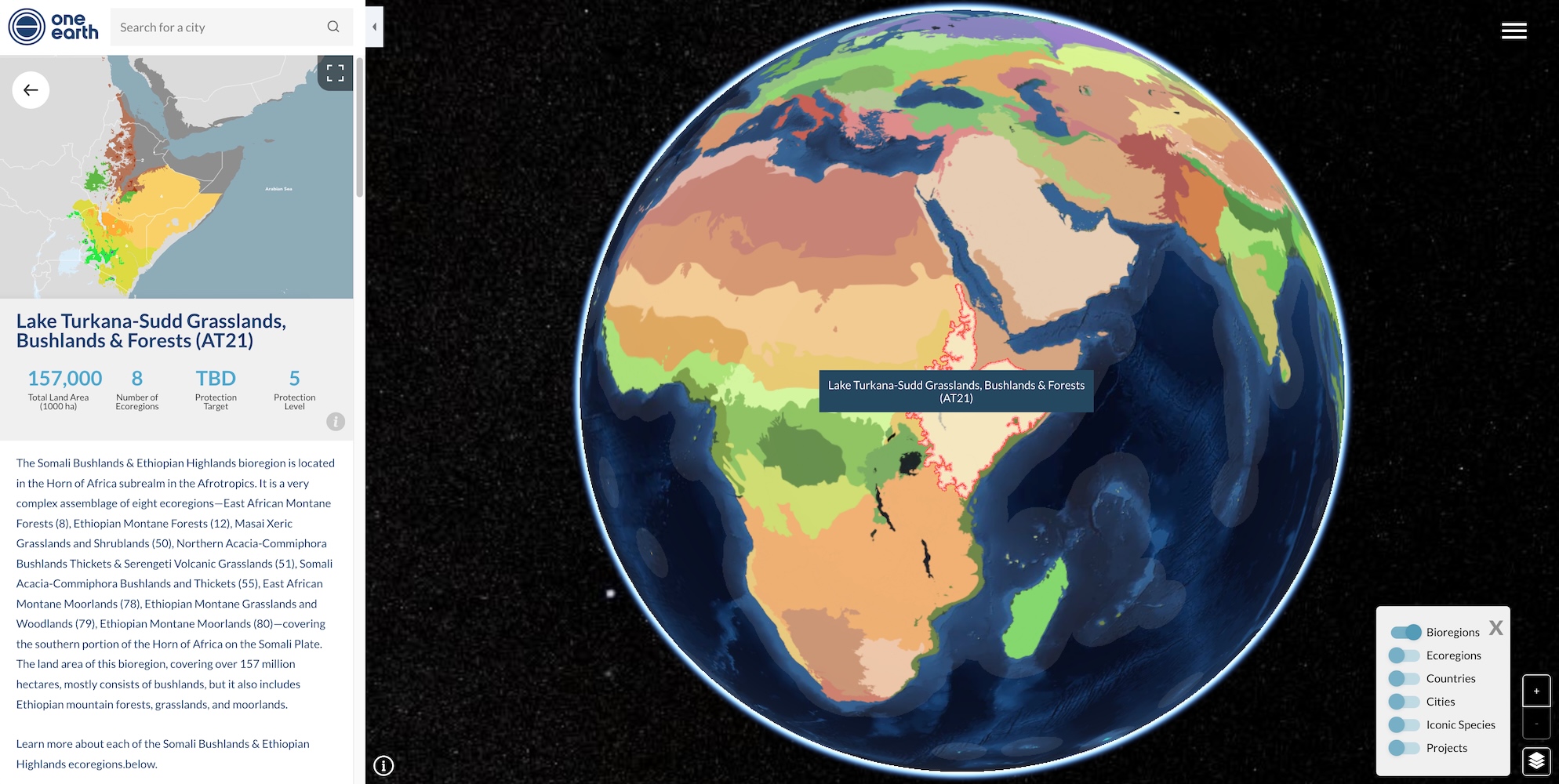

Bioregion AT21 in the Afrotropics realm displayed on the One Earth Global Navigator.

Bioregionalism and its global potential

Matthew Monahan: Bioregionalism seems to be gaining traction as a way to rethink how we manage land and ecosystems. What work has One Earth done to advance this concept?

Karl Burkart: Bioregionalism is foundational to how we approach conservation. It’s based on the idea that ecosystems and human systems should align with natural boundaries, not political ones. Nature doesn’t recognize country borders, so we grouped 844 ecoregions into 185 bioregions using data science and ecological principles. These bioregions reflect natural features like watersheds, climate zones, and topography.

This framework helps us track progress toward conservation goals and manage resources more effectively. For instance, instead of treating the Amazon as parts of multiple countries, we treat it as a unified ecological system, making it easier to prioritize and coordinate conservation efforts.

Matthew Monahan: What challenges arise when defining bioregions?

Karl Burkart: The biggest challenge is that nature doesn’t have hard lines. Species migrate, ecosystems shift, and environmental conditions change. However, for practical purposes, we need boundaries to measure progress and allocate resources. Our bioregional model provides a clear structure while acknowledging that these lines are approximations.

Bioregions also help ensure representation in global conservation efforts. For example, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework emphasizes the need to represent all ecoregions in protected area networks. Bioregions give us a way to ensure this representation is equitable and data-driven.

Matthew Monahan: How do bioregions influence conservation financing?

Karl Burkart: Bioregions could revolutionize how conservation is funded. Imagine a global system where resources flow into bioregional financing facilities based on ecological need. These facilities could aggregate funding from various sources—philanthropy, impact investing, or even a global financial mechanism like a transaction tax.

This approach allows for targeted investment in areas with the highest ecological importance. It also supports grassroots organizations, which often manage critical projects but lack access to large-scale funding. By channeling resources directly to bioregions, we can make conservation more effective and equitable.

Matthew Monahan: Where do you see bioregionalism heading in the future?

Karl Burkart: I believe bioregionalism will shape how we manage the planet in the 21st century. It’s a framework that aligns human systems with nature, creating a sustainable way to balance conservation, resource management, and human well-being. The concept is still evolving, but it has the potential to fundamentally reshape global conservation and governance.

.png)

Map of the Amazonia categorized in priority areas, intactness, low degradation, high degradation, and transformation. Image Credit: RAISG.

The path forward for conservation and nature-based solutions

Matthew Monahan: As you reflect on the evolution of these models and frameworks, where do you see the greatest opportunities for impact in the next few years?

Karl Burkart: The opportunities lie in scaling conservation financing, improving accountability, and integrating nature-based solutions into global systems. Conservation Imperatives and the Global Safety Net have laid the groundwork for identifying priority areas, but now we need to ensure the resources reach those who are protecting these ecosystems—especially Indigenous communities.

A key focus should be on bioregional financing facilities. These offer a scalable way to channel funding directly into ecosystems based on ecological and community needs. At the same time, innovative mechanisms like carbon credits, transaction taxes, or Earth fees can help close the massive funding gap. But these efforts must center equity, ensuring that local communities, particularly Indigenous stewards, are supported and empowered.

Matthew Monahan: What trends are you seeing in the integration of nature and climate solutions, particularly at events like Climate Week?

Karl Burkart: It’s encouraging to see the shift from “Climate Week” to “Climate and Nature Week.” This reflects growing recognition of how intertwined these issues are. For instance, nature is a critical carbon sink, and biodiversity underpins food security and human health. However, despite this progress, nature solutions still receive a fraction of the funding that climate solutions do.

Momentum is building around bioregionalism and localized conservation efforts, which I think will play a big role in future strategies. These approaches ensure that conservation aligns with the realities of ecosystems and the needs of the people living in them.

Matthew Monahan: What message do you want funders and decision-makers to take away from your work?

Karl Burkart: The main message is that we have the tools, models, and data to act now. The science is clear, and the pathways are defined. What’s missing is the financial commitment to scale these efforts globally. Funders and decision-makers need to focus on the areas of greatest need and ensure that their investments are equitable and sustainable.

Ultimately, this is about more than protecting land or reducing emissions—it’s about building a resilient planet where nature and humanity can thrive together.

The time to act is now.

Explore the Solutions Framework