If Nature Could Draw a Map of the World | Karl Burkart | TEDxPorto

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Ecosystem Restoration

- Wildlife Connectivity

- Biodiversity

- Nature/Climate Finance

- Policy & Governance

One Earth's co-founder and Deputy Director Karl Burkart was invited to present at TEDx Countdown in Portugal as part of a summit focusing on the governance of the global commons. The talk, entitled “If Nature Could Draw a Map of the World,” delves into the origins of One Earth’s innovative Bioregions framework.

It starts with the publication of a major peer-reviewed paper called A Global Deal For Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets which introduced the 30x30 and 50% global conservation targets.

It goes on to discuss how critical ecosystem services and the biodiversity that makes them possible are not incorporated into our modern global climate economic system and explains how the One Earth Bioregions framework was developed and how it could be used to facilitate nature-based collective action.

It ends with a discussion of a second peer-reviewed paper, A “Global Safety Net” to reverse biodiversity loss and stabilize Earth’s climate, and an approach to provide basic conservation income to local communities safeguarding ecosystems through the implementation of an “Earth Fee.”

Watch the full presentation below.

1. Introduction

If Nature could draw a map of the world, what would it look like?

We’ve grown accustomed to seeing our world divided into countries and states, but there is another way to see, and better understand, the planet we call home.

In a few minutes, I’m going to unveil a new map of the world, organized by bioregions, or as I like to describe them, “nature’s countries.”

I’ll explain how we developed this map, but you are probably wondering—why create a new map in the first place?

Well, after the success of the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, many of us were looking forward towards the UN Biodiversity Convention, which would set the global agenda for preserving nature.

We knew the targets set in the previous US convention had not been sufficient—with now more than 2/3 of all land animals and 80% of freshwater populations wiped out since the 1970s [1].

It was 2017, and no one had yet aligned on a central target for this convention, so my organization brought together some of the brightest minds to answer a vexing question:

How much of our lands and oceans do we need to conserve in order to solve the twin crises of biodiversity loss and climate change?

The result was a paper published in 2019 called “A Global Deal for Nature..” which introduced in the scientific literature the “30x30 target”—protecting and conserving 30% of lands and seas by 2030 [2].

With a big diplomatic effort, the target was adopted at the end of last year as part of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework [3]. This is one major step toward a larger goal of protecting half of the planet.

Now, the work begins. And part of that work involves rethinking how we organize collective action in the future. While the architecture of the UN agreement is, of course, centered on nation-states, nature organizes things in a very different way..

If we are to truly succeed in preserving biodiversity as part of the global commons, we believe that we’ll need to follow nature’s architecture. So how does it work?

2. The Problem

We all just took a breath that was freely given to us by nature, manufactured by oceanic plankton and trillions of trees that tirelessly absorb carbon dioxide from the air and release back oxygen via the process of photosynthesis.

As Paulo Magalhães from Common Home of Humanity has described it, we have a global operating system for the planet, akin to software system that is owned by no one but which regulates everything—from weather patterns and precipitation to atmospheric conditions and even ocean tides.

These processes, while essential to life on Earth, are completely unacknowledged in our current global economic system.

We’d be tempted to blame the Bretton Woods economists for our troubles—for ignoring the totally obvious fact that nature is the foundation of all economies and, if abused, can decline into oblivion.

But back in 1944, those men couldn’t see what was coming just around the corner…

While a small group of scientists did know about climate change [4], no one realized how rapidly the increased use of fossil fuels would transform our atmosphere into a hothouse, unleashing catastrophic impacts—from severe storms and sea level rise to drought and mass migrations.

And since that time, we’ve made things much worse by leveling nearly one billion hectares of forest, an area the size of the entire United States [5]. These forests are vital to daily life, supplying fresh water to billions of people and regulating the climate system.

The creators of our modern economy naively invented a world order that simply didn’t price in the value of nature or the costs of destroying it. 80 years on, we’re careening toward an apocalypse that we all AGREE we want to avoid but seem incapable of stopping.

To survive in the coming decades, we will need a mechanism designed to ensure the longevity of the global commons, specifically renumerating the local communities that safeguard ecosystems for the benefit of all of humanity.

Let’s dive in for a minute to just one ecosystem service of many—carbon flux—and how such a mechanism could work to support it.

3. Nature's Contributions

Carbon flux is like the Earth breathing—releasing hundreds of billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, then reabsorbing back that CO2 every year.

For thousands of years, this dynamic has been quite precisely balanced, but today, humans add an additional 40 billion tons of CO2 annually [6]. Nature is able to take on about half of that carbon, storing it in forests and oceans, which is very fortunate... Without this essential service, we would all be toast by now.

Here’s how it works.. In the oceans, phytoplankton takes in ambient carbon; Krill gobble up the plankton; whales eat the krill and deposit that carbon in deep ocean sediments, where it is safely locked away.

In forests, animals like tapirs and toucans act as seed dispersers, constantly planting new trees and shrubs. Other animals, like forest elephants, prune back the trees, enabling ecosystems to store more carbon. And predators like wolves ensure that herbivores don’t overgraze the plants.

This vast menagerie of animals and plants is what animates our global carbon cycle.. and they do it for free.

But it shouldn’t be for free! As we’ve seen, some countries, like Brazil and Indonesia, have allowed rampant deforestation. Why? Because there is no real financial incentive to keep forests standing. In our current economic system, nature is only valued when it’s dead (or harvested), not when it’s alive.

The first attempt to solve this problem was the carbon market, which allows polluters to offset their impacts by providing funds for conservation. But this approach has created perverse incentives..

Countries like Gabon or Bhutan, which have done an excellent job preserving their forests and biodiversity, can’t really access this market because carbon credits are issued primarily based on the threat of deforestation... So countries that cut down the most trees make the most money, not the other way around.

In the long run, this approach will not be sufficient to deliver the permanent funding needed to protect and conserve nature at scale.

So let’s envision a system that could achieve this and how a new map of the world can help in implementing the preservation of our global commons.

4. The Solution

To protect the intricate web of life that makes carbon flux and other ecosystem services possible, it’s estimated that we’ll need about $600B per year in conservation funding. Currently, carbon credits, philanthropy, and government spending currently provide about $140B [7]. So there’s a big gap.

How can we fill it? Let’s imagine for a minute if we were able to insert a tiny, almost invisible, transaction fee into the machinery of global capitalism..

Every quarter, $750 trillion dollars in currencies, stocks, and bonds are traded. If we applied just one basis point—or 1/100th of a percent fee—to currency trades and another four basis points to stocks & bonds, this would yield $380 billion dollars in new annual funding [8].

In addition to helping stabilize markets in general, this tiny “Earth Fee” could close much of the biodiversity funding gap with a relative snap of the fingers. How, then, would all this money get allocated?

Peering into the future to imagine a huge new flow of capital to support the global commons, one thing becomes clear: We will need to move beyond a purely jurisdictional map of the Earth.

Nature doesn’t care too much about the political boundaries that we humans draw and redraw on our maps. Ecosystems often span multiple jurisdictions, which are often nested in complicated ways that can impede the funding flows -- with the possibility for conflicting bureaucracies or administrative corruption.

Some futurists like Julian Cribb have even predicted the collapse of the nation-state altogether as the primary instrument of governance in the 21st century—triggered by climate change and other societal pressures [9].

Whether or not this comes to pass, to effectively allocate capital for the global commons, we will need a science-based approach optimized for the specific needs of each ecosystem.

Instead of applying a geopolitical rubric to the distribution of capital, we should be thinking about a biogeographical one, which honors the architecture of the natural world and allocates resources based on the extent of intact natural habitat contained within each of the world’s bioregions.

So, let’s now dive into the Bioregions map, which offers such a rubric.

5. Bioregions 2023

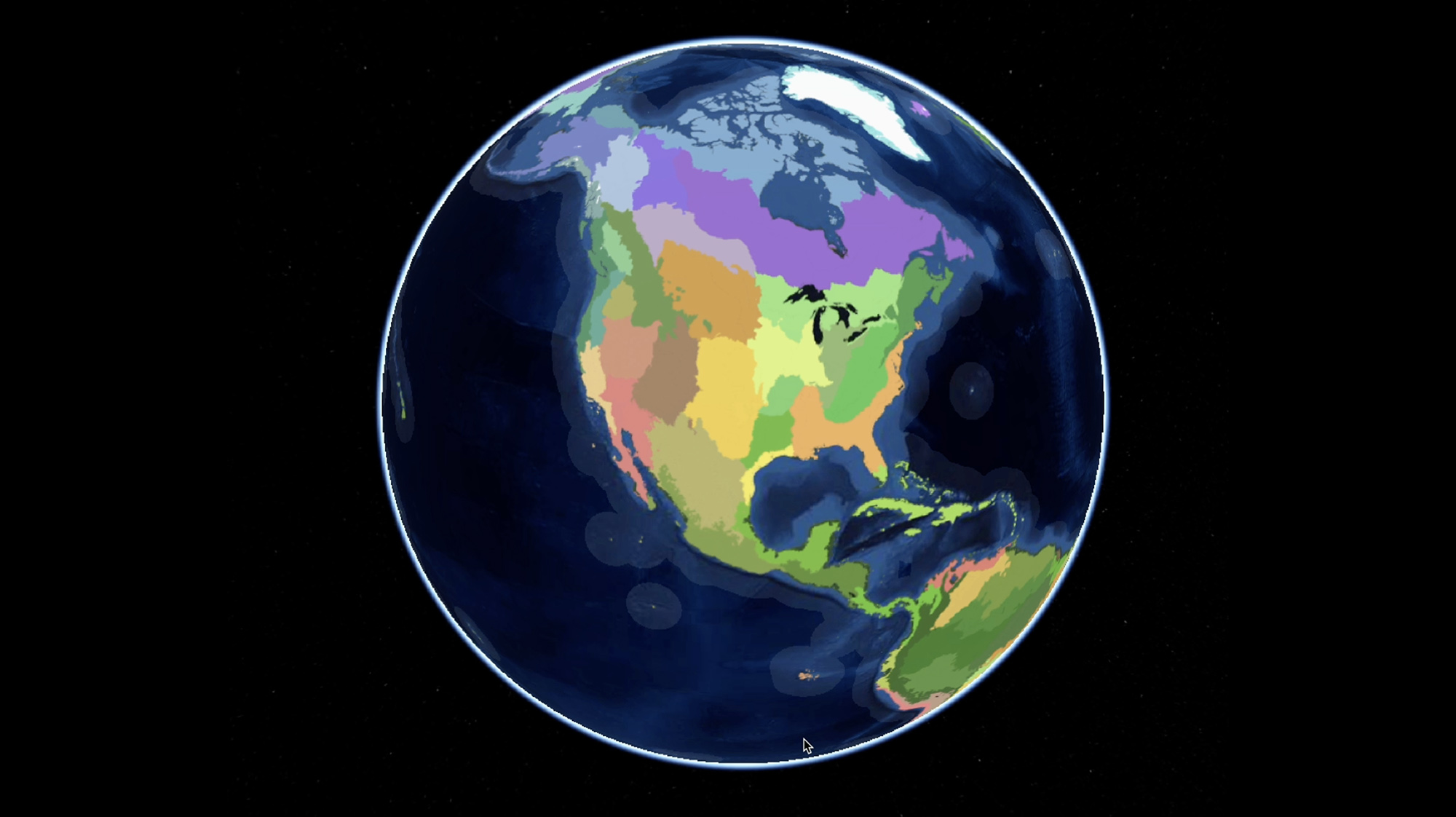

Here, I present the One Earth biogeographical framework, which was developed with input from many scientists and experts to delineate a new set of 185 discreet bioregions [10].

What is a bioregion? A bioregion is a geographical area defined not by political boundaries but by ecological systems. It is smaller in scale than a biogeographical realm but larger than an ecoregion or an ecosystem.

Conceptually, the bioregions are subdivisions of the Earth’s 14 major biomes—a classification of broad landscape types adapted to certain climatic conditions found across many continents—from forest and grassland to desert and tundra.

These are further organized into component subrealms aligning with well-known geographical regions like Amazonia, which overlaps 8 Latin American countries, or the Great Plains, which spans the heartland of the United States.

The bioregions are built upon a landmark 2017 study that identifies 844 unique terrestrial ecoregions [11]. Five rules were applied to delineate the bioregions, grouping closely related ecoregions across all realms.

- First, Bioregions must be contained within a realm. A bioregion cannot cross over from one realm to another

- Second, Bioregions subdivide the major biomes by intersecting them with large-scale geological structures or climate zones

- Third, Bioregions consist predominantly of one biome type but can incorporate ecoregions belonging to another when they are closely linked together

- Fourth, Ecoregions are the building blocks of each bioregion. An ecoregion is never split between two bioregions, with the exception of mangroves that span long coastal distances

- Fifth, Bioregions include the marine areas beyond the coastline, demarcated by the economic zones of each country, as these waters are biologically impacted by fishing and onshore activities.

6. Global Safety Net

With this new map of the world, we can now think about the flow of resources needed to protect critical ecosystems commensurate with the specific needs and conditions of each bioregion.

Going back to our futuristic vision where we have an extra $380 billion per year to spend on nature, we could deploy that capital against an inventory of intact natural habitats.

Many of the same scientists who worked on the original ‘Global Deal for Nature’ paper published a geospatial analysis entitled “A Global Safety Net,” which compiled a sweeping inventory of remaining land that preserves ecosystem functionality [12].

The results, which we’re now updating in higher resolution, found that approximately 50% of the world’s land is in a natural condition across six broad classifications.

But this land is not equally distributed around the world. Some bioregions have a lot more intact natural land than others. And some areas, like tropical forests and wetlands, are more costly to maintain than others. So, each bioregion needs its own strategy.

Some of the most important regions for biodiversity are found on Indigenous territories, showing the urgent need to secure legal tenure and financial support for these communities.

By bringing together the bioregional framework with a routinely updated inventory of globally significant land for biodiversity, we can start to envision a science-based mechanism for allocating huge amounts of capital for Nature.

Each bioregion could develop its own permanent trust, receiving funds annually in perpetuity based on the extent of its natural habitat [13]. These trusts would be tailored to the specific needs of local communities within the bioregion, who are working to preserve the vitality of their ecosystems.

This idea is in line with a concept called Conservation Basic Income, which redistributes a portion of the global economy’s net productivity to those local communities that safeguard nature [14].

Through this approach, we can localize the global commons, creating a just, equitable, and science-based approach to conserving the biodiversity that makes all life on Earth possible.

-

-

[1] Almond et al. (WWF), Living Planet Report 2022. Link>

[2] Dinerstein et al. “A Global Deal For Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets”, Science Advances, 2019. Link>

[3] UNEP, Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Link>

[4] UKRI, “A brief history of climate change discoveries”. Link>

[5] We estimate total deforestation using a decadal average of 115 Mha from the 1940s through the 1990s. The average rate dropped to 70 Mha in the 2000s and to 50 Mha 2010-2019. Since 2019 we’ve seen an additional 7 Mha of deforestation, totaling roughly 933 Mha per H. Ritchie, “Decadal Losses in Global Forest Cover..” Source: Our World in Data

[6] IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (WGIII), Figure SPM.1.

[7] UNDP Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN), “Investing in the Planet’s Safety Net.” Link>

[8] Every quarter an estimated $680 trillion in currencies and $70 trillion in equities are traded globally. ($680T x 4 x .01%) = $270B; ($70T x 4 *.04%) = $110B $380B/yr

[9] J. Cribb, 2023. “The nation state is on the skids..” Link>

[10] K. Burkart, One Earth. Bioregions 2023.

[11] Dinerstein et al. “An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm”, BioScience, 2017. Link>

[12] Dinerstein et al. “A ‘Global Safety Net’ to reverse biodiversity loss and stabilize Earth’s climate”, Science Advances, 2020. Link>

[13] Levitt & Navalkha, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, From the Ground Up: How Land Trusts and Conservancies Are Providing Solutions to Climate Change, 2022. Link>

[14] de Lange et al. “A global conservation basic income to safeguard biodiversity”, Nature Sustainability, 2023. Link>

-