Reefscape: a global reef survey to build better satellites for coral conservation

Coral reefs are special places. They contain thousands of species often assembled in kaleidoscopic patterns that defy both our scientific understanding and our imagination. Reef ecosystems feed millions of people and protect our shorelines, acting as buffers to waves and storms. The corals, fish, invertebrates and other creatures residing in reef ecosystems vary greatly from region to region, generating an exciting global-scale tourism industry: a trip to the Caribbean turns up species that can’t be found in the Pacific Ocean; swim off a beach in Indonesia, and you’ll find reef inhabitants different from those in the Red Sea. Coral reefs are said to be the rainforests of the ocean, and indeed, the untrained eye often finds that discerning coral species on a reef is similar in experience to telling tree species apart in the jungle.

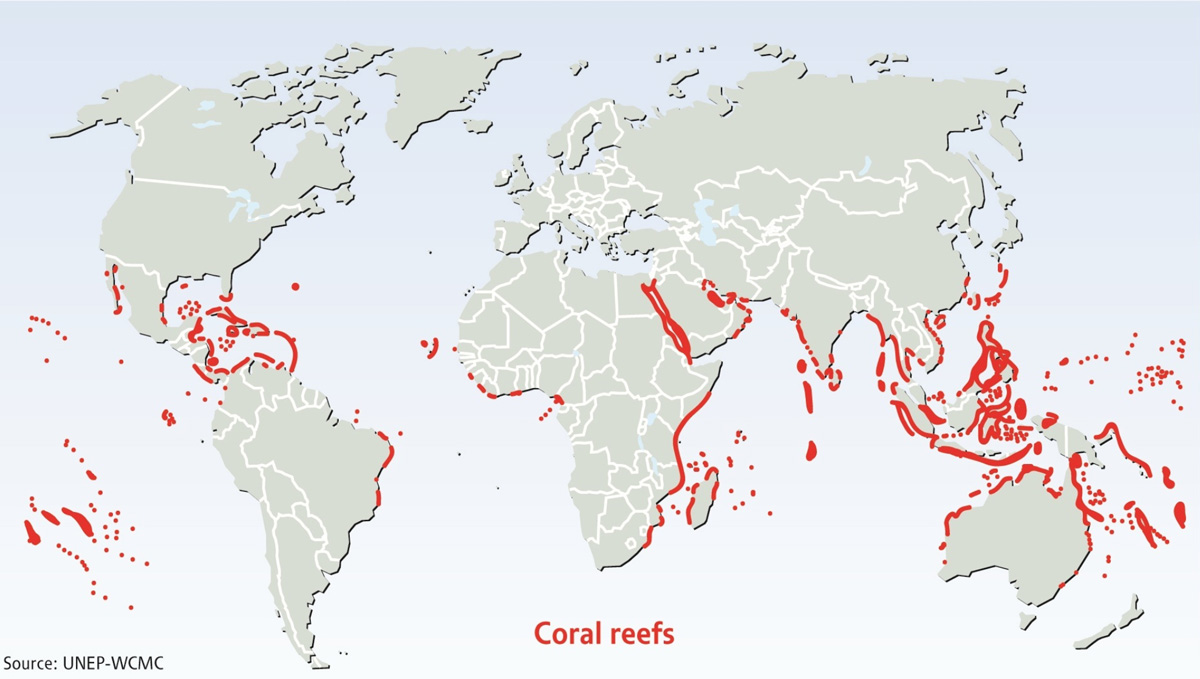

Coral reefs around the world.

Photo courtesy of UNEP-WCMC

While science has documented only a small portion of reef species that occur around our planet, we do know that human activities have taken an extensive toll on reef ecosystems worldwide. Massive areas of reef have been physically removed by society’s seaside and offshore activities. Even larger areas of coral reef have been degraded by global stressors linked to carbon dioxide emissions from industry, transportation and other human activities. Ocean temperatures are spiking, resulting in coral-bleaching events that destroy vast swaths of reefscape, and ocean acidification is having a negative impact on coral health and growth.

Coral bleaching in the 2015 ocean warming event in the Hawaiian Islands.

Photo courtesy of Greg Asner

Despite our growing knowledge of how coral reefs are changing around the world, the geography of these changes remains extremely hard to piece together. Reefs in one region respond to stressors differently than reefs in another, and within a reef, individual species react differently. During coral-bleaching events, for example, there are often winners and losers within a given reef, making it difficult to predict whether the ecosystem as a whole will bounce back. This variation among corals is matched by unknown variation among key reef-dwelling fish and invertebrates, the fates of which are linked to that of corals. Given that coral reefs span an estimated 500,000 square kilometers (193,000 square miles) in total area, spread over more than 200 million square kilometers (77.2 million square miles) of ocean, it is no wonder that the state of global reefs remains poorly known today.

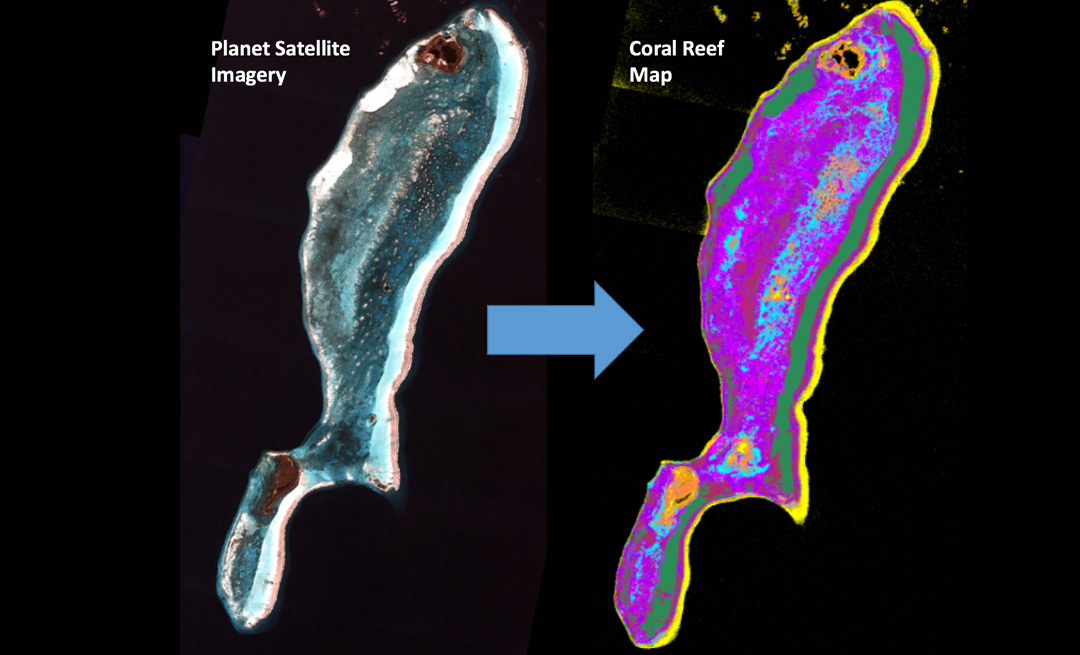

To gather a more comprehensive understanding of the condition of global reef ecosystems, we need a way to assess and monitor them on a large geographic scale. New satellites, such as those from Planet (formerly Planet Labs), are, as of 2017, able to capture near-daily imagery of coral reefs worldwide. Planet’s high-resolution imagery of reef location provides us with an at-your-fingertips understanding of the extent of shallow, horizontally oriented reefs. Satellites miss the vertically inclined reefs — the so-called reef walls — but are evolving to facilitate monitoring the most vulnerable shallow horizontal reef areas over time. Currently, no satellites can provide a way to assess reef health at the resolution of individual or clusters of corals and other reef inhabitants. For this, we need a new satellite mission.

Planet imagery allows for mapping of shallow coral reefs, such as on Lighthouse Reef Atoll in Belize.

Photo courtesy of Planet Inc.

With our partners, we are planning a new satellite mission for global reef ecosystems, a mission that will advance our ability not only to map reef extent, as we can do now with Planet’s current fleet of satellites, but also to monitor changes in coral reef health. The mission concept centers on global-scale reef monitoring using detailed spectral information, which we and others have advanced from high-flying aircraft. A high-tech approach called imaging spectroscopy measures the spectrum of sunlight scattered and absorbed by an object. These spectral patterns differ based on a given object’s unique chemical signature, and so can be used to assess changes in reef health over time.

Imaging spectroscopy provides a detailed mapping of coral reefs including some coral species and their health.

Photo courtesy of Carnegie Airborne Observatory .

To lay the groundwork for a new satellite mission, it is important to develop a baseline understanding of current reef extent, and to pair that information with field-based assessments of reef condition. In addition, improved spectral libraries of corals are required to drive the new satellite design and approach for global monitoring.

Divers collect the spectral properties of corals in preparation for future satellite missions.

Photo courtesy of Chris Balzotti

The Reefscape project aims to improve our understanding of the condition of coral reefs worldwide, while simultaneously developing spectral libraries needed to advance the development of a new satellite mission. A global-scale field study is a daunting task, and we will need to select regions that maximize our understanding of global reef conditions while collecting the field-based spectral data. Given the magnitude of this undertaking, we and our sponsors decided to take advantage of the unique information and perspectives we will gain in the field and start an outreach component to the project. We hope that our combination of hard-core biology and old-fashioned naturalist reporting will elevate awareness of the state of coral reefs in 2018, as viewed through the lens of spatial ecologists like ourselves. With your help, we can use the Reefscape project to communicate the geography of reef conditions and to get the conservation community prepared for a high-tech satellite mission that will transform how we monitor coral reefs in the next decade and beyond.

This article was originally published on Mongabay.