In 2018, the IPCC made clear that the world must be kept below 1.5°C global average temperature rise. The special report Global Warming of 1.5°C showed that it becomes increasingly difficult to solve climate change beyond this threshold, and every tenth of a degree increase in temperature risks multiplying impacts. Some believe the 1.5°C goal can only be achieved through large-scale implementation of risky or expensive technologies, such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), direct air capture (DAC), or solar radiation management (SRM). These technologies may play a role in the future, but they cannot be relied upon to solve the current climate crisis.

A groundbreaking climate modeling framework, published in the book Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals (APCAG), shows that it is still possible to stay below 1.5°C with widely available, rapidly scalable solutions. The effort was the culmination of a two-year collaboration with 17 leading scientists at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), two institutes at the German Aerospace Center (DLR), and the University of Melbourne’s Climate & Energy College. The book was released by the prestigious scientific publisher Springer Nature and is now the most downloaded climate text in the publisher’s history.

In order to create a global decarbonization model to achieve the 1.5°C goal, a sophisticated computer simulation of the world’s electrical grids was created with 10 regional and 72 sub-regional energy grids modeled in hourly increments to the year 2050, along with a comprehensive assessment of regionally available renewable resources like wind and solar, minerals required for manufacturing of components, energy efficiency measures, and configurations for meeting projected energy demand and electricity storage for all sectors through 2050. Below are the results for the Europe energy transition:

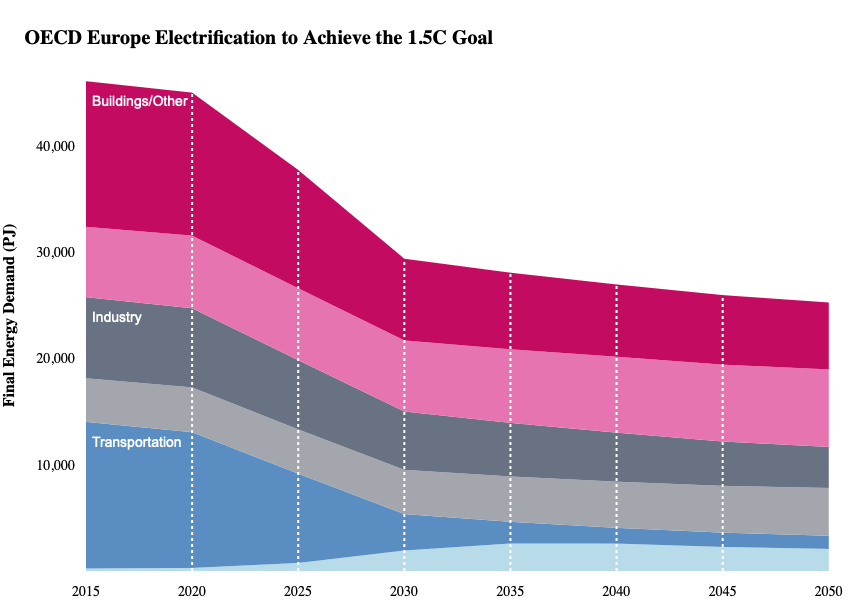

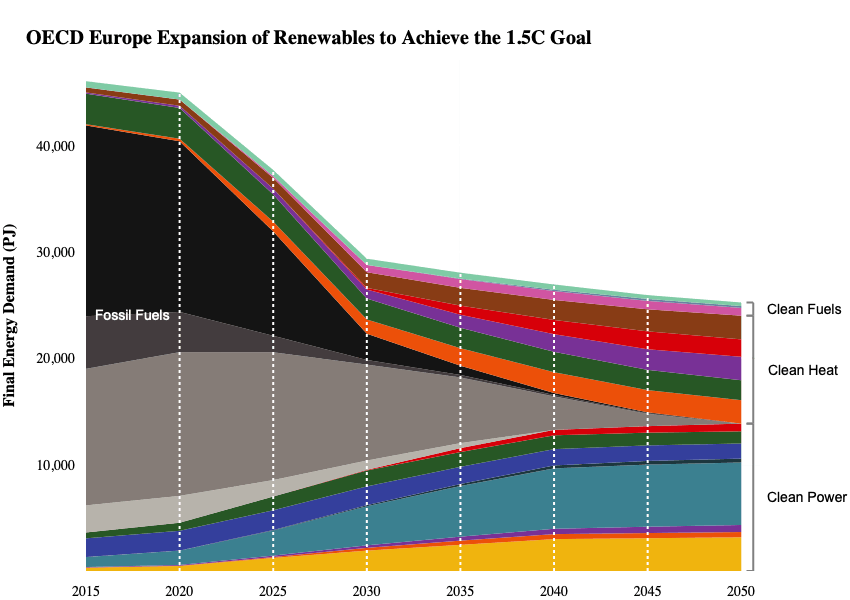

In order for Europe to achieve the goal of 1.5°C, all member states that currently have renewable electricity and energy efficiency targets and policies need to implement them. Southern Europe has high solar potential and low heat demand for buildings. Northern and Western Europe have high wind potential, especially offshore. Northern and Central Europe have high potential for hydropower and a high energy demand for space heating. The European Network of Transmission System Operators (ENTSO-E) can be used as a well-established basis for the further development of an interconnected European grid. Large-scale importation of solar thermal electricity from MENA countries via high-voltage lines is a promising long-term option. Cars with internal combustion engines using oil-based fuels will need to be phased out by 2040. All European lignite power plants will need to cease operations by 2035, and the last hard coal power plant will go offline in the same timeframe. Mouse over the charts below at 5-year increments to see data points for each transition.

This region includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Austria, Belgium, Czechia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, Ireland, the United Kingdom and small islands. To explore the global transition model read the APCAG Executive Briefing.

OECD Europe Electrification of the three major sectors -- transportation, industry, and buildings/other -- required to achieve the 1.5°C goal per Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals (Teske, 2019). Credit: University of Southern California Marshall MS Business Analytics Program

OECD Europe Expansion of renewable energy delivery required to achieve the 1.5°C goal per Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals (Teske, 2019). Lower curves show renewable electricity generation. Upper curves show renewable heating sources and renewable fuels. Credit: University of Southern California Marshall MS Business Analytics Program