The African wild dog: Painted wolf of the savannas

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Mammal Assemblages

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Horn of Africa

- Afrotropics Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

The African wild dog (Lycaon pictus, or “painted wolf”) is also known as the Cape hunting dog or painted dog—a reference to the striking, multicolored mosaic patterns of their beautiful coats.

With the unique social dynamics of their packs and highly complex hunting strategies, these highly social and intelligent apex predators have played a vital role in maintaining the balance of African ecosystems. Yet, they are one of Africa’s most endangered carnivores.

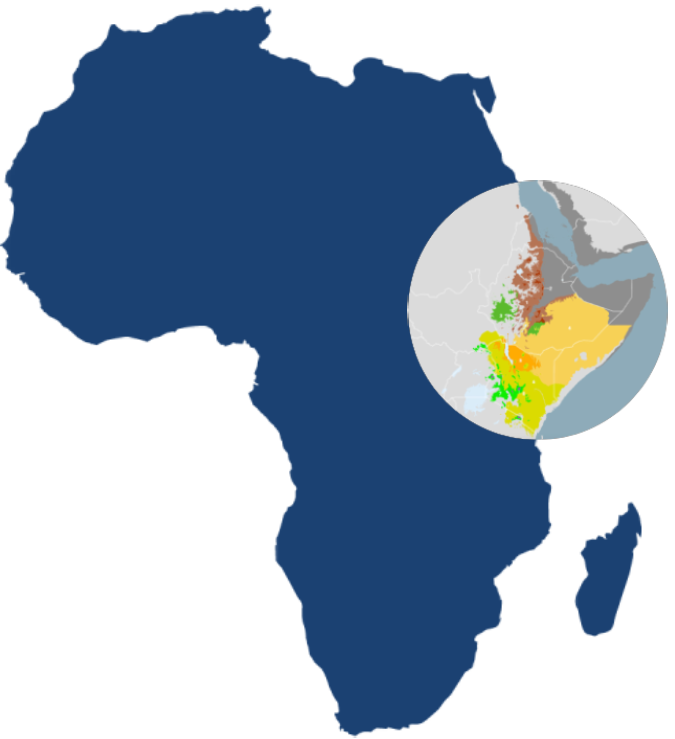

The African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) is the iconic species of the Somali Bushlands & Ethiopian Highlands bioregion (AT21) located in the Horn of Africa subrealm of the Afrotropics.

From ancestral wolves to nomadic savanna predators

During the Pleistocene, around two million years ago, African wild dogs diverged from a common ancestor they shared with wolves. Although they were once found in desert to mountain habitats throughout the African continent, they have disappeared from most of their geographic range—due mainly to human pressures.

Now, they typically roam the vast open savannas and sparse woodlands of sub-Saharan Africa, where their largest populations are found in Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Zambia, Tanzania, and Mozambique.

African wild dogs thrive in cohesive packs, patrolling huge territories that can stretch over 1,500 square kilometers (580 square miles), and traveling around 50 kilometers (30 miles) in a single day. Their nomadic lifestyle mirrors the dynamic nature of their ecosystems, allowing them to adapt to constantly shifting habitat conditions and herd movements.

Unique coats and built for speed

The irregular patterns on the coats of African wild dogs are unique to each dog, featuring patches of red, black, brown, white, and yellow fur. Large, rounded ears are designed for keen hearing, and their lean bodies, great lung capacity, and long, slender legs are designed for endurance and agility, enabling them to navigate dense vegetation easily over long distances.

While other canids are five-toed, these dogs have only four toes on each foot with the pads of the middle digits connected by dermal webbing, thought to enhance their speed and maneuverability. Although they’re able to reach a top, greyhound-like sprint speed of 72 kilometers per hour (45 mph), their hunts rely on the endurance required to run their exhausted quarries to a standstill. Very sharp, large premolars then allow them to consume large quantities of meat and bone swiftly—before other predators such as lions and hyenas can encroach on their kill.

In addition to vocal communication, comparative anatomist Heather Smith and her colleagues made this finding about the African wild dogs' expressive communication in 2019. The study was published in The Anatomical Record.

The power of the pack's communication and cooperation

African wild dogs are highly social, communicating with each other through frequent vocalizations, touch, and other behaviors. Amazingly, it’s been discovered recently that African wild dogs use a system of meaningful sneezes to “vote” on group decisions before a hunt, which is characterized by complex, strategic team tactics and coordination.

Their formidable packs number from six to twenty dogs who are among the world’s most skillful and proficient hunters, with a success rate of 80% as compared to lions’ 30%. This is attributed to the constant communication maintained throughout a hunt, during which they check in on their pack mates with vocal calls conveying their own locations and that of their prey to adapt strategies. Success is also due to the close social bonds they’ve formed with each other. A pack will come to the fierce and courageous defense of every individual.

Diet and altruistic feeding behavior

African wild dogs are opportunistic feeders, preying primarily on small to medium-sized ungulates such as impalas and gazelles, as well as warthogs and wildebeest (which were likely more common when the dog packs were larger). They supplement their diets with rodents and birds, and also scavenge carrion when it’s available.

After a kill, all pack members will feed equally regardless of their rank or whether they participated in the hunt, and pups and yearlings always feed first. Pack members are also altruistic, assisting and sharing food with their weak, ill, injured, and elderly members.

An African wild dog puppy with a piece of reed in his mouth. Image credit: © Klomsky | Dreamstime

Pack leadership and reproduction dynamics

African wild dog packs are led by an older dominant female and a young dominant male, who form a monogamous breeding pair and dominate subordinates of both sexes. Juvenile males are most likely to stay with the pack, whereas females often emigrate.

While subordinate females may also reproduce, their offspring seldom survive. More often, these females develop pseudopregnancies and may lactate to help care for the pups of the dominant pair.

The dominant female has a litter of two to 20 pups which are then cared for by the entire pack, which regurgitates food to the pups while they’re still in the den. At 11–12 weeks of age, the pups are weaned and start to follow the pack.

Keystone species as ecological architects

Beyond their prowess as hunters, African wild dogs serve as keystone species in their ecosystems. Their regulation of herbivore populations prevents overgrazing and maintains the integrity of vegetation communities.

It also contributes to nutrient cycling, enriching the soil and fostering plant growth. Africa’s wild dogs serve the same essential ecosystem function as their faraway wolf relatives, as architects of healthy, balanced biodiversity.

.jpg)

A pack of African wild dogs in Tsavo West Park, Kenya. Image credit: © Philippe Demande | Dreamstime

Cultural significance and enduring symbolism

Highly respected by the ancient Egyptians as symbols of order over chaos, African wild dogs were often depicted on cosmetic palettes from the Predynastic Period. Across the African continent, Indigenous cultures have revered them as symbols of strength, unity, and perseverance.

In traditional folklore, they are frequently depicted as guardians of the land, entrusted with the task of preserving the natural order—an ecological role we now recognize. One prevalent myth portrays these dogs as emissaries of the spirit world, possessing the wisdom to guide lost souls on their journeys to the afterlife.

The Indigenous San people of Botswana (once known as the ‘Bushmen’) see the African wild dog as the embodiment of the ultimate hunter and believe that shamans can shape-shift into painted dogs. San hunters sometimes apply the bodily fluids of wild dogs to their feet in the hopes that they will be granted the dogs’ stamina, agility, and courage.

Through the millennia, their enduring symbolism reflects the deep-seated respect and admiration that humans have held for these unique canids.

The multifaceted threats for survival

Despite their cultural significance and ecological importance, African wild dogs have been on the IUCN Endangered Species List since 1990, and face myriad threats that jeopardize their survival.

Habitat loss driven by the encroachment of human settlement and agricultural expansion has fragmented their territories and restricted their movements. Predation by lions and competition with spotted hyenas pose additional challenges to their survival, as does the spread of diseases such as rabies and canine distemper.

Although the expansion of human settlements has led to conflict with livestock farmers, significant predation is rare, as the dogs prefer wild prey. Still, in many areas, farmers shoot them on sight or leave poisoned meat at their dens to eliminate entire packs. One of the traits that helped early peoples domesticate wolves was their willingness to join human communities, but African wild dogs have given humans a wide berth.

Climate change has only exacerbated these threats, altering the distribution of prey species and disrupting the dogs’ established hunting patterns.

Throughout history, African wild dogs have been revered by various cultures for their strength, unity, and symbolic roles in preserving natural order. Image credit: Charles J. Sharp, Wiki Commons

Initiatives for habitat connectivity and conflict reduction

African wild dogs are among the many species that would benefit from the creation of protected wildlife corridors that help connect their increasingly fragmented habitats. Conservation groups are also working on initiatives that reduce conflict between humans and African wild dogs, including educational efforts that offer farmers training in livestock management techniques that prevent predation. As is occurring with North American wolves, awareness initiatives are underway to dispel persistent myths about the dogs.

Rewilding large mammals for ecosystem restoration

In addition to focused conservation efforts for African wild dogs, reintroducing large mammal assemblages has shown significant potential for ecosystem restoration. A One Earth supported study reveals that rewilding just 20 large mammal species, including brown bears, bison, and wild horses, can restore over 8.5 million square kilometers of land globally.

These large mammals act as landscape engineers, shaping plant life and wildlife, enhancing nutrient cycling, and maintaining ecosystem balance. By reintroducing species such as the African wild dog, lion, and hippopotamus in strategic locations, vast areas of land can regain their ecological integrity, benefiting biodiversity and human communities alike.

.jpg)

Reintroducing species like African wild dogs can significantly restore ecosystems and enhance biodiversity. Image credit: Mathias Appel, Wiki Commons

Hope through conservation efforts

There are approximately 6,600 African wild dogs left, with another 600 captive in zoos, where they often fail to thrive. The IUCN reports that their population level is likely in an irreversible decline.

The hope is that the grim outlook for these wonderful canids will shift to one of optimism through the support of conservation initiatives aimed at preserving their habitats, preventing diseases, and mitigating human-wildlife conflicts.

Support Nature Conservation