The American bison: How this powerful icon is restoring the prairie

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Mammal Assemblages

- Species Rewilding

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Southeast US Savannas & Forests

- Northern America Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

In North America, stretching from southern Canada into Texas, spanning between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, lies an abundant landscape. The Great Plains contain an assortment of habitats including prairies, steppes, and grasslands. It is home to a variety of biodiversity, but one keystone species makes this ecosystem thrive.

The American bison (Bison bison) or American buffalo, is an essential grazer, helping maintain the balance of vegetation and therefore all life on the prairie. Their story is as turbulent as the storms that strike this region, from living in harmony and revered in Indigenous cultures, to their dramatic decline in the 19th century due to overhunting and habitat loss. Now, their reintroduction stands as one of the greatest examples of conservation success, symbolizing both ecological revival and the honoring of Native American heritage.

American bison (Bison bison) are iconic species of the Southern Mixed Forests & Blackland Prairies (NA28), located in the Southeast US Savannas & Forests subrealm of Northern America.

Symbols of strength and survival through millennia

Surviving the last Ice Age, bison have been on this planet for over 2.6 million years. Global symbols of strength, they can weigh up to 907 kilograms (2,000 lb) and have a body length of 3.7 meters (12 ft). Their temperament is often unpredictable. American bison can appear peaceful and almost lackadaisical as they bask in the sun in a shallow depression called a bison wallow. The next minute, they can be on their hooves and in a fight with one another or an elk, using their large heads and horns as battering rams.

Ecosystem engineers through speed and size

Moving up to speeds of 56 kilometers per hour (35 mph), American bison cover long distances to graze. They have specialized stomachs, which give them the ability to ferment vegetation prior to digestion. It is with this movement and diet that they help the prairie flourish. As they forage, their weight and constant eating prune the grasslands. So much so, they lengthen the growing season.

An American bison bull stands strong in the Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Image credit: © Geoffrey Kuchera | Dreamstime

Directly impacting the survival of other species

These rich grasslands create habitats for other keystone species like black-tailed prairie dogs, which serve as food for predators and also help cultivate the plains. Birds use bison fur to line their nests, providing much-needed warmth as the climate here drastically varies.

Droughts are also prone to this region, and the bison wallows create pools of water that many animals use as their primary drinking source. Even in death, bison alter the ecosystem. Their carcasses are rich with digested seeds that eventually burst into patches of wildflowers and grasses, which feed essential pollinators like birds and bees.

A Buffalo Warrior Kachina doll. Kachina can represent anything from a revered ancestor, to an element, a location, a quality, a natural phenomenon, or a concept. There are more than 400 different kachinas in Hopi and Pueblo culture. Image credit: © Marilyn Gould | Dreamstime

The buffalo’s integral role in Indigenous life and spirituality

Known as iinniiwa in Blackfoot, tatanka in Lakota, ivanbito in Navajo, and kuts in Paiute, the American buffalo is the most significant animal to many Indigenous American nations. For thousands of years, Native Americans relied heavily on bison for their survival and well-being, using every part of the animal for food, clothing, shelter, tools, jewelry, and ceremonies.

The buffalo holds profound spiritual significance, deeply woven into the cultural and religious practices of many tribes. Honoring the animal's role in providing for the community, the buffalo is often placed at the center of the creation story, symbolizing life, abundance, and sustenance.

The Sioux, for example, view the birth of a white buffalo as a sacred event, heralding the return of White Buffalo Calf Woman, a prophetess who brought them their most sacred rituals and spiritual practices. The Mandan and Hidatsa tribes revered the White Buffalo Cow Society as the most sacred of women's traditions, reflecting the animal's importance in their cultural heritage.

“The Buffalo was part of us, his flesh and blood being absorbed by us until it became our own flesh and blood. Our clothing, our tipis, everything we needed for life came from the buffalo's body. It was hard to say where the animals ended and the human began.”—John (Fire) Lame Deer, Oglala-Lame Deer Seeker of Visions.

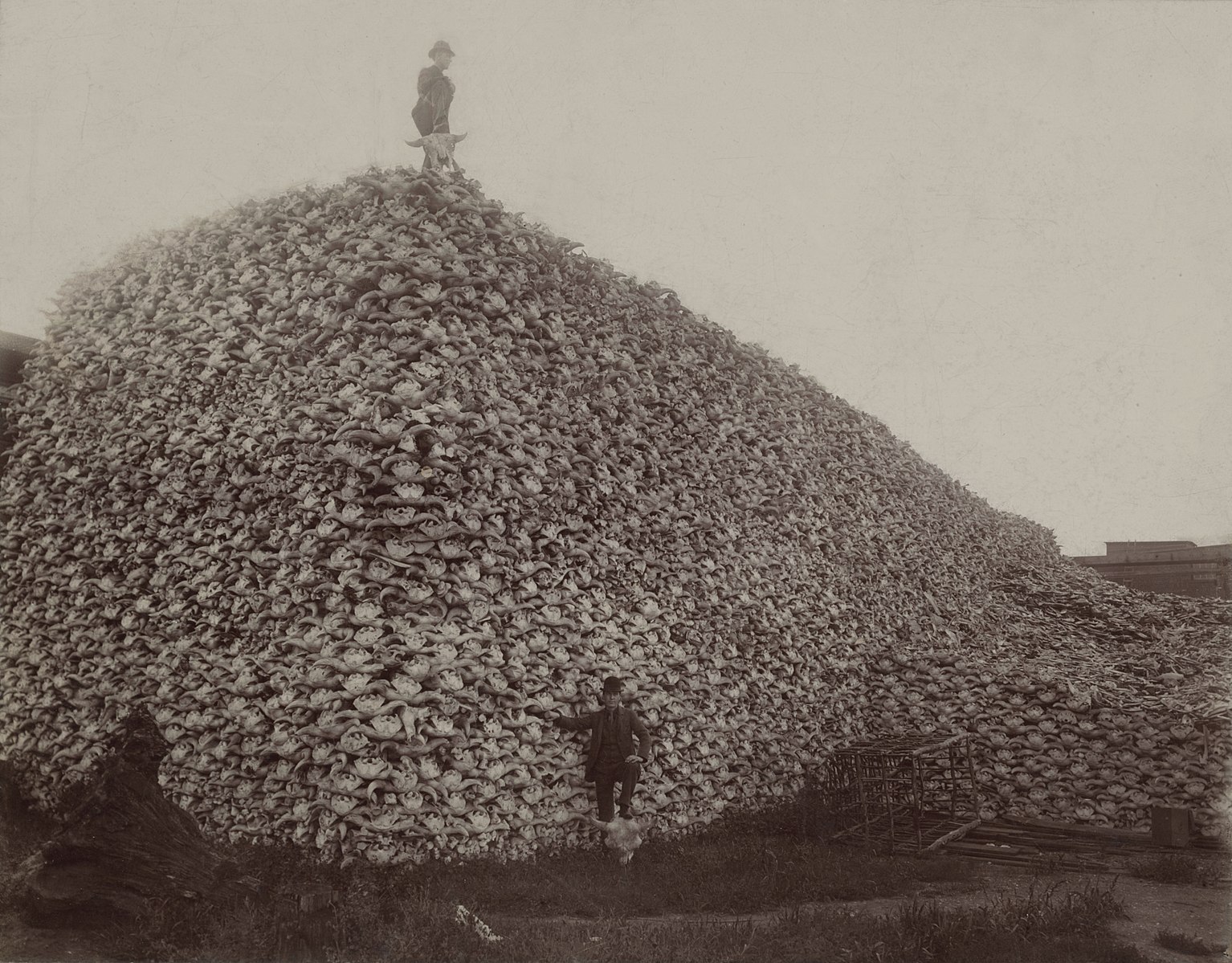

The dark side of American history: Buffalo slaughter and the starvation of the Native Americans

Historically, researchers estimate that 25-60 million bison roamed the Great Plains. Yet, in the 19th century, settlers and hunters nearly drove them to extinction. This was not just a consequence of overhunting, but a deliberate strategy used by the US government and settlers. By systematically slaughtering the buffalo, the plan aimed to destroy the foundation of Indigenous life and force them onto reservations.

The mass killing of bison was a brutal campaign. Hunters killed millions, leaving their carcasses to rot on the plains. The impact was devastating, nearly wiping out the buffalo and leading to widespread starvation, poverty, and cultural disintegration among the Plains tribes.

The loss of the buffalo, a sacred animal deeply intertwined with their spiritual and cultural identity, was a profound blow to Indigenous communities. This tragic chapter in history emphasizes the critical need for current conservation efforts to restore bison populations, not only to restore the prairies but also to heal, honor, and support the revival of Native American cultures and traditions.

One of the infamous photographs of a pile of bison skulls, depicting the mass slaughter of the American buffalo, taken in the mid-1870s. Image Credit: Wiki Commons.

Healing the land and people through conservation efforts

Remarkably, a small herd of buffalo escaped the slaughter and found refuge in the newly established Yellowstone National Park. This small remnant of two dozen individuals marked the starting point for a monumental conservation journey.

A coalition of biologists and environmental activists set about recovering the American bison with the Yellowstone herd. Through dedicated breeding programs, their population grew to almost 5,000. This effort expanded, further rewilding buffalo in the plains, and has been so successful that their impact on the landscape can be seen from space.

Today, the mission to restore bison populations continues with renewed vigor. The conservation organization American Prairie, in partnership with Earthjustice, a non-profit environmental law group, aims to see thousands of bison once again roaming free. By purchasing private ranching land in Montana, their mission is to create a three-million-acre nature reserve. Similar programs are being established across the United States, in places such as South Dakota and Colorado.

Additionally, over 60 tribes are actively involved in reintroducing buffalo to their lands. This initiative reinforces the deep-rooted connection between the bison and Indigenous ways of life, ensuring that this sacred animal continues to thrive both in Nature and in the hearts of the people who hold it dear. This concerted effort honors the resilience of both the bison and Indigenous cultures, symbolizing a profound healing of both ecological and cultural landscapes.

%20(1).jpeg)

A herd of bison moves quickly along the Firehole River in Yellowstone National Park. Image credit: Royce Bair | Flickr

New study highlights the power of reintroducing keystone species like the American bison

New research, funded by One Earth and led by RESOLVE and the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, reveals reintroducing large mammal assemblages has shown significant potential for ecosystem restoration. The study identifies that rewilding just 20 large mammal species, including the American bison, can restore over 8.5 million square kilometers of land globally.

This approach supports global biodiversity objectives and can be a central pillar of area-based conservation efforts, emphasizing the important link between biodiversity and climate resilience.

By reintroducing keystone species like the American bison, we are not only revitalizing the Great Plains, but also fostering a deeper connection to the natural world and honoring the cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples. This holistic approach to conservation promises a future where ecosystems and communities alike can thrive.

Support Global Rewilding Efforts%20Waterton%20Lakes%20National%20Park%2C%20Alberta%20AdobeStock_34912613.jpeg?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=1440)