Inside the world of coconut crabs: The largest land arthropod

Beneath the swaying palms of remote tropical islands, a giant roams the shores—an arthropod so remarkable it has captured imaginations for centuries. The coconut crab (Birgus latro), known for its immense size and unique adaptations, thrives as one of nature’s most extraordinary creatures.

From scaling trees in search of food to playing a vital role in island ecosystems, this enigmatic crab offers a fascinating glimpse into life on the fringe of the sea and land.

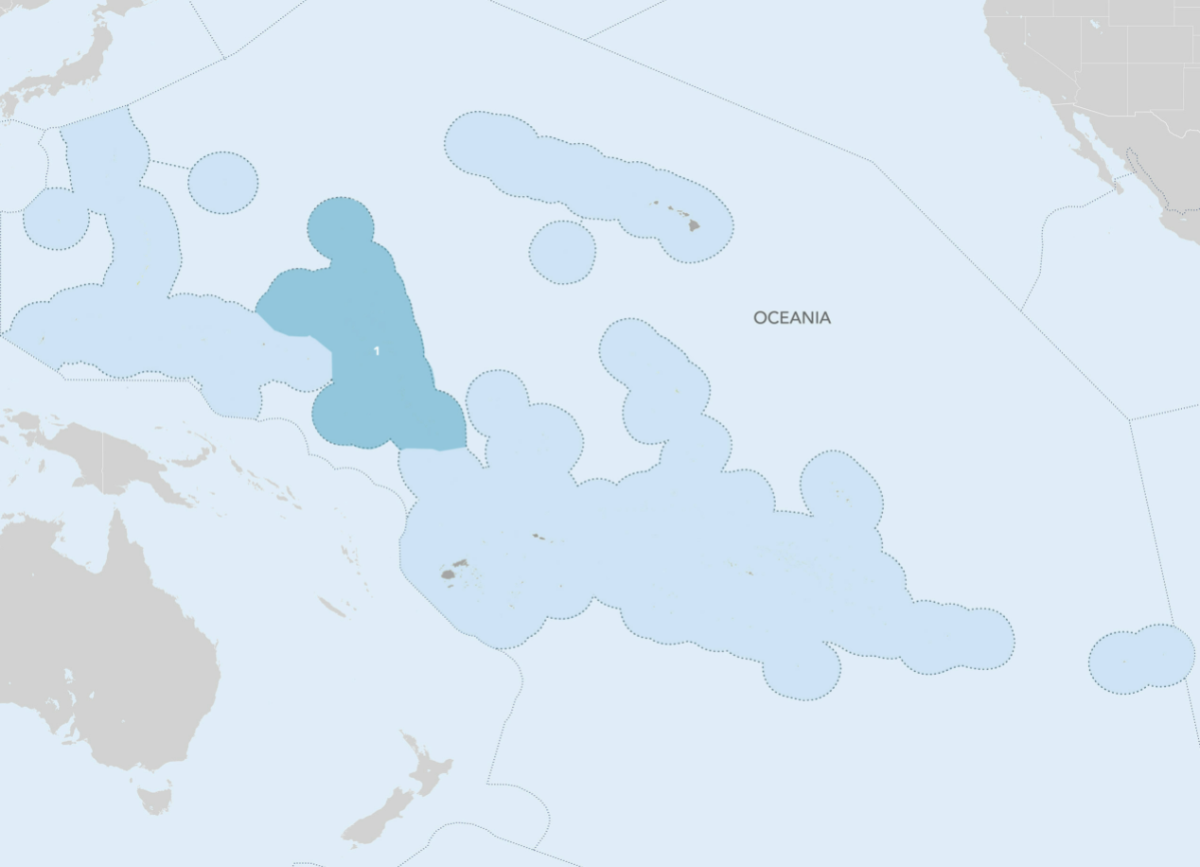

Coconut crabs are the iconic species of the East Micronesian Islands bioregion (OC7), located in the Oceania realm.

Life on shores across oceans

Coconut crabs inhabit tropical islands across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, thriving in warm climates from Zanzibar in the west to the Gambier Islands in the east. Their range closely aligns with the distribution of coconut palms, though human activity has severely reduced their presence in many regions, including mainland Australia and Madagascar.

These crabs create burrows in sandy soils and hide among rocks or tree roots, ensuring moisture retention for their land-adapted breathing structures. Christmas Island is home to one of the densest populations, though they share the island with far more numerous red crabs.

The giants of the islands

Coconut crabs are the largest terrestrial arthropods on Earth, reaching weights of up to 4.1 kilograms (9 lbs) and leg spans exceeding 1 meter (3 feet 3 inches). Their body structure reflects significant evolutionary adaptations, with a hardened exoskeleton providing protection and reducing water loss.

The front claws, or chelae, are powerful enough to crack coconuts and exert a force comparable to the bite of a lion, measured at up to 3,300 newtons. Their vibrant coloration varies by location, ranging from orange-red to purplish-blue, with males typically larger than females.

A coconut crab on Christmas Island with a vibrant blue hue. Image Credit: Maciek Gornisiewicz, Flickr.

Omnivores with an opportunistic diet

Although associated with coconuts, these crabs have a broad and adaptable diet. They primarily feed on fruits, seeds, nuts, and decaying plant material but also consume carrion, bird chicks, and other crustaceans.

Their ability to climb trees allows them to reach food sources such as pandanus fruit. Coconuts are opened using a specialized technique, starting by stripping the husk and cracking the shell near the germination pores with their claws. They are essential scavengers, recycling nutrients and maintaining the health of their ecosystems.

Nature’s cleanup crew and seed dispersers

As scavengers and opportunistic predators, coconut crabs play a critical ecological role. By breaking down organic material and consuming animal carcasses, they contribute to nutrient cycling.

Their predation on smaller animals and competition with other species, such as red crabs and rats, influence population dynamics on the islands. These crabs also inadvertently aid in seed dispersal, particularly for fruits they partially consume and leave behind.

A coconut crab on its coconut dinner in Niue. Image Credit: fearlessRich, Wiki Commons.

Masters of land adaptation

Unlike their aquatic relatives, coconut crabs breathe using specialized branchiostegal lungs, which function more like primitive lungs than traditional gills. Juveniles rely on gastropod shells for protection but develop calcified abdomens as they mature, allowing them to move freely without carrying a shell.

Adult coconut crabs cannot swim and will drown if submerged for extended periods. Their acute sense of smell, resembling that of insects, enables them to detect food over long distances, highlighting their sophisticated terrestrial adaptations.

A remarkable reproductive journey

Reproduction among coconut crabs is a delicate balance between their terrestrial nature and the aquatic origins of their species. Mating occurs on land, with females carrying fertilized eggs attached to their abdomens for several months. At the hatching stage, females make a perilous journey to the ocean’s edge, where they release their larvae.

These planktonic larvae drift for 3–4 weeks, undergoing various developmental stages before settling to the seafloor. Those that survive return to land, where they begin their life as juvenile hermit crabs in shells. Sexual maturity takes about five years, while the full life span can exceed 60 years, with some estimates suggesting up to 120 years.

Polynesian coconut crab art. Image Credit: MataiByCharles purchased via Etsy.

Cultural connections with island communities

Coconut crabs hold a special place in the cultures of many Pacific and Indian Ocean communities. While regarded as a delicacy and aphrodisiac in some regions, taboos and myths surrounding the species exist in others.

On the Nicobar Islands, consuming the crab is believed to bring misfortune, while in the Cook Islands, it is associated with ancestral spirits. These beliefs have helped preserve local populations in certain areas, highlighting the intertwined relationship between traditional practices and conservation.

Under threat from humans and habitat loss

Coconut crabs face significant threats due to habitat destruction, overharvesting, and the introduction of invasive predators. Their large size and the quality of their meat make them a target for hunting, leading to localized extinctions on populated islands.

Coastal development further reduces the availability of suitable habitats, pushing populations to the brink in some areas. They are particularly vulnerable during their molting phase, when they remain hidden for weeks as their exoskeleton hardens.

Coconut crabs are known as robber crabs or palm thieves on the island. Image Credit: DIAC Images, Animalia.bio.

Safeguarding the future of coconut crabs

Listed as vulnerable by the IUCN, coconut crabs benefit from targeted conservation measures in some regions. These include size limits for hunting, bans on capturing egg-bearing females, and the establishment of marine conservation areas.

For example, the Funafuti Conservation Area in Tuvalu offers refuge for coconut crabs on its motu (islets). Despite these efforts, more research and international cooperation are needed to address the broader threats to their survival and ensure this remarkable species continues to thrive.

Support Ocean Conservation

.webp?auto=compress%2Cformat&h=600&w=600)