Life in the hot Mediterranean highlands with Cuvier’s gazelle

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- North Africa

- Southern Eurasia Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

The Cuvier’s gazelle (Gazella cuvieri) is one of the three species of antelope that form the biocultural landscape of the Maghreb in northern Africa, across Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia.

Locally, it is known in Algeria and Tunisia as edmi in Arabic, while in Eastern Morocco, it is the dama. In Southwestern Morocco, it is known as the harmouch. It shares a habitat with the dorcas gazelle (Gazella dorcas) and the slender-horned gazelle (Gazella leptoceros).

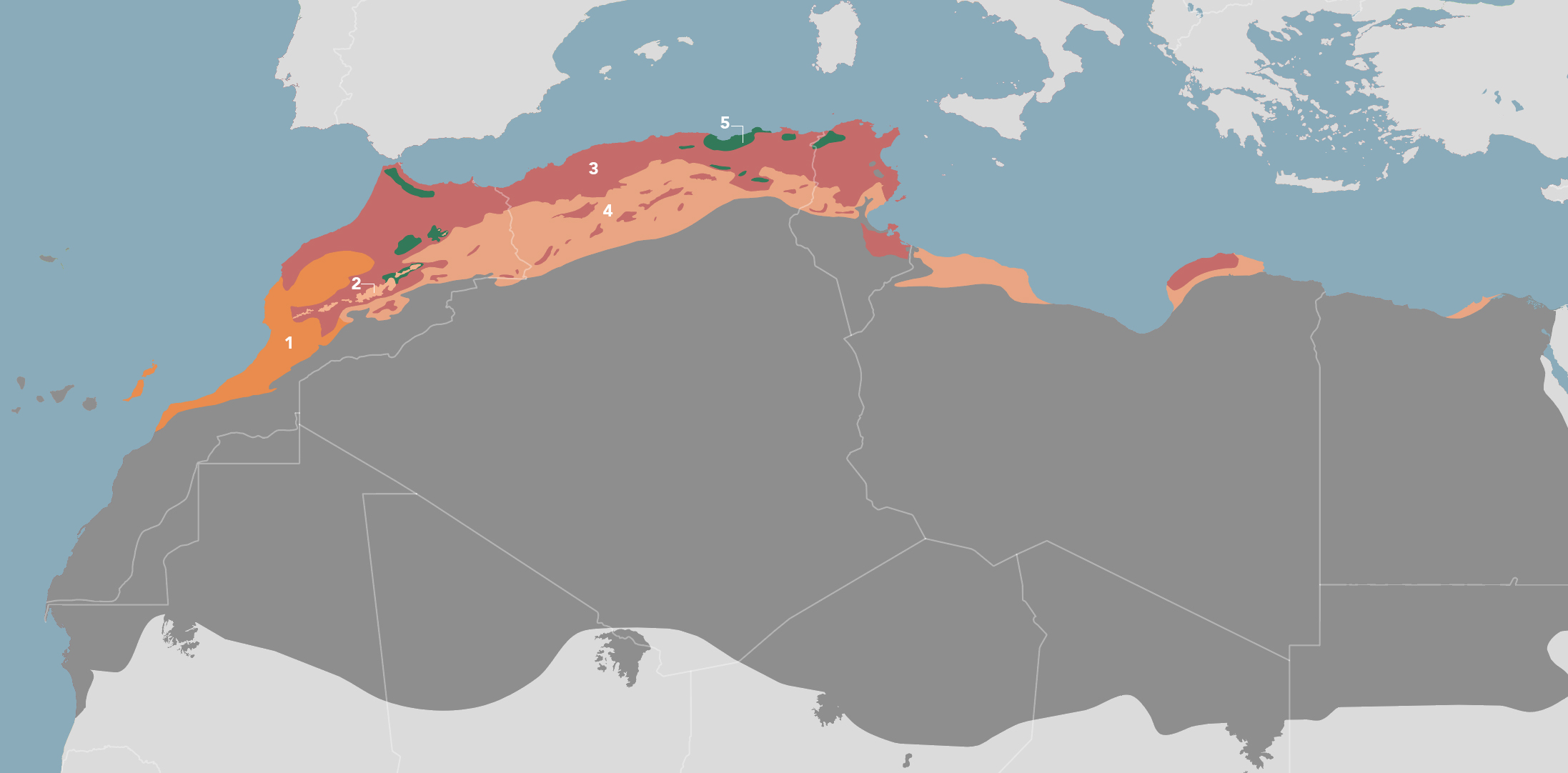

Cuvier’s gazelle is the Iconic Species of the South Mediterranean Mixed Woodlands & Forests Bioregion (PA23).

Distinct horns and a dark coat for camouflage

A medium-sized antelope, the Cuvier’s gazelle measures up to 68 centimeters tall (around 27 in) at the shoulder and weighs around 25 kilograms among females and 35 kilograms for males (between 44 and 55 lb). Its dark coat makes it less conspicuous among the oak and pine trees or while resting under the shade of large rocks.

Its hair is rather long, rough, and coarse. A distinct dark-brown lateral band runs across the fore and rear flanks in contrast to its white belly and rump patch. The top of the nose has a prominent black spot, and black stripes run along the sides of the face towards narrow and pale ears.

Both females and males have horns that measure 25 to 37 centimeters (9- 14 in) long and have distinctive thick rings. The horns rise vertically before diverging out and back, and the tips of the horns curve in and forward.

Relying on plants for food and hydration

The gazelles spend most of the day ruminating leaves, grasses, and herbs. They are both browsers and grazers, eating herbs and shrubs in the summer and green grasses in winter.

Grasses include alfa grass shoots (Stipa tenacissima) and Cynodon dactylon. They also feed on leaves of leguminous plants and other perennial herbs and cereal where it grows, as in Tiaret, Algeria. In wintertime, they feed on holm oak (Quercus ilex) leaves and acorns, as well as on Pinus halepensis and Cuppressus spp.

This diet helps prune their ecosystem’s vegetation and brings new plant life by dispersing seeds in the gazelles’ droppings.

Due to the high temperatures of their habitat, the gazelles primarily feed at night and before dawn. Dew droplets help their hydration, but they also must visit watering holes. The formation of these waterholes depends on the season, the local climate, and geographic characteristics.

While in the Atlas Mountains, it rains 600 millimeters (24 inches) per year on average, the desert on the northern fringes of the Sahara may see no water for years.

Reproduction and life in a group

Living in small groups of three to six individuals, a male gazelle watches over one or more females and their young. Gestation lasts around half a year, and births occur in April and May with a single new calf.

Threats to their habitat

The intensification of urban sprawl along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coast, along with deforestation for agriculture, grazing, and burning to make charcoal are all factors that have shrunk and fragmented the Cuvier’s gazelle historic range.

Over the past decades, the gazelles have occupied a few dozen small patches within the Middle and High Atlas Mountains, the Western Anti-Atlas, and further south, in the Northwestern Sahara. This latter region is mainly visited a few weeks after rainfalls when pastures emerge.

Successful conservation efforts in Tunisia

The conservation status of the Cuvier’s gazelle is vulnerable, according to the IUCN Red List. However, in Morocco, it is considered endangered.

After Cuvier’s gazelle almost disappeared, the Tunisian government started a conservation program along the Tunisia Dorsale. One of the outstanding features of the Dorsale is the Chambi Massif, a system of projecting rocks surrounded by a succession of vegetation communities. This area was turned into the Chambi National Park over twenty years ago when there was an estimated 300 gazelles.

The Tunisian conservation program provides waterholes and areas free of intruders in the buffer zone around the park. In 2015, the Tunisian government and Spain signed a cooperation protocol where 43 gazelles were transferred to Djebel Serj National Park.

More protection is needed in Algeria and Morocco

In Algeria, there is an excellent population of Cuvier’s gazelle in Djebel Boukhil that only nomads, local people, and hunters know well. According to the Directorate-General of Forests, the population size throughout the country is estimated at around 500 to 560 individuals. Moving forward, special attention should be granted to regulate excessive hunting for skin, meat, and trophies, as well as any obstacles impeding the natural displacement of the gazelles, such as highways.

Morocco also recognizes the need for better and more coordinated conservation efforts. The IUCN noted that subpopulations could disappear due to poaching and habitat loss. Unfortunately, illegal hunting is common even in areas not accessible by motorized vehicles.

Remembering the cultural value of Cuvier’s gazelle

The species is considered a marabout, sacred, in the Tiaret region, Northwest Algeria, and in Relizane-Mascara in the Beni Chougran Mountains. This is what Farid Bounaceur shared with her IUCN colleagues during a workshop held in Malaga in 2013.

In the Arabian tradition of northern Africa, a Marabout is a holy, hermit man with supernatural powers. This sacred regard for the gazelles and animals, in general, should lead local conservation campaigns. It would dignify animals for what they are and empower local people who feel they have no say when poachers take over their lands with greedy intentions.

Education is crucial, for the intense pressure from illegal buyers can only be stopped by creating awareness about how keeping the gazelle alive and thriving in its natural habitat contributes to the balance of the whole bioregion and beyond.

In the last IUCN workshop, it became evident that on-the-ground training for management staff and financial resources needs to be improved for proper conservation. The ideal scenario for the coming years is one where local people can be trained to monitor and protect the Cuvier’s gazelle and other wildlife species.

With community-led conservation, both people and wildlife can prosper together. It would help ensure Cuvier’s gazelles roam the Mediterranean woodlands for generations.

Explore the Bioregions