Gray bats are the ultimate planners when it comes to having young

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Northeast American Forests

- Northern America Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

The gray bat (Myotis grisescens) is a medium-sized insectivorous bat with an overall length of about 3.5 inches and a wingspan of 10 to 11 inches. Weights range between approximately 7 to 16 grams. The fur of gray bats is gray, but the hair often bleaches to reddish-brown as summer approaches.

Based on band recovery data, the oldest known gray bat is at least 13 years and 6 months old. Most recaptured gray bats are much younger.

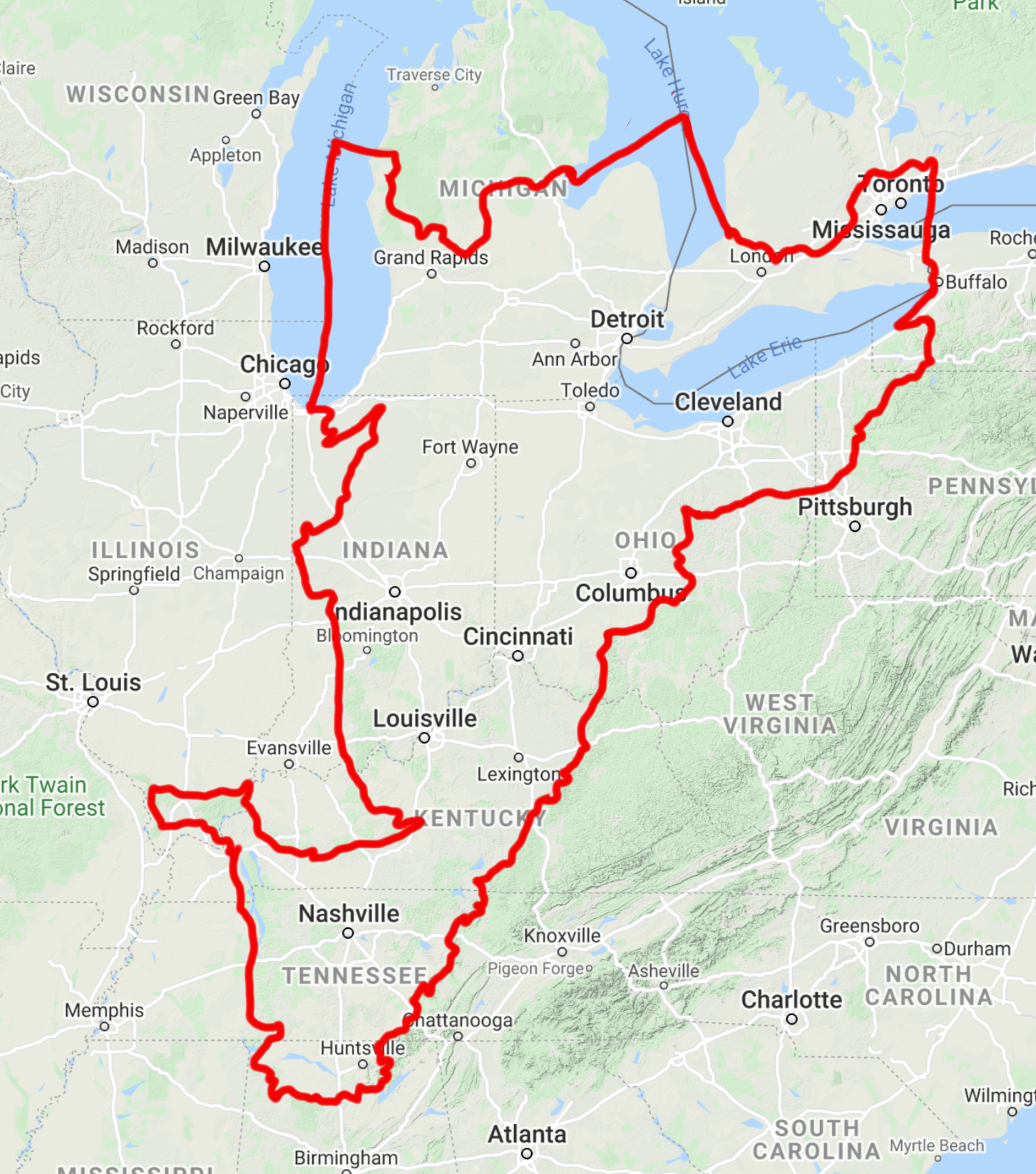

The gray bat is the iconic species of the Interior Plateau & Southern Great Lakes Forests Bioregion (NA23).

Dwelling and hibernation

The gray bat’s dwelling is restricted to the southeastern and midwestern United States. This region’s main geological feature is its limestone karst landscape with long underground chambers, caves, sinkholes and springs, an ideal sanctuary for bat overall. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, almost 100% of the population specimens hibernate in only 15 caves, while Bat Conservation International has reported that they only use 9 caves to hibernate.

One such cave system, Mammoth-Flint Ridge, is near the boundary of the Interior Plateau US Hardwood Forests in Kentucky. It has 663 km of passageways, and it is by far the world’s longest-known cave system. Over millions of years, it has become the home to several species of bats, including the gray bat and the Indiana bat, providing ideal conditions for different bat species to keep their colonies stable and healthy.

Gray bats need to occupy caves or cave-like structures year-round. Although gray bats prefer to roost in caves near large water bodies, there are records of them commuting up to 20 miles to the nearest large water body from its roosting location each night.

Summer and winter colonies have distinct patterns of cave occupation and roosting behavior. Summer colonies have been documented using not just caves but dams, mines, quarries, concrete box culverts, and the undersides of bridges. Summer caves must be warm or have restricted rooms that can trap the body heat of clustered bats.

The range of summer colonies extends eastward from eastern Oklahoma and very southeastern Kansas, across southern Illinois and Indiana, and out to southwestern Virginia, western North Carolina, and the northwest section of Georgia. Gray bat summer colonies can use one or multiple caves along a stream, river, or reservoir but are sometimes located further, within commuting distance of a water body.

Winter hibernation sites are often deep vertical caves that trap large volumes of cold air; these caves are naturally very rare. Hibernating populations are concentrated in caves across northern Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee.

Because of the limited number of suitable caves, gray bats may migrate as many as 500 miles between summer and winter caves. However, based on band recovery data and the distribution of hibernacula or caves and summer colonies across the range, most gray bats are considered regional migrants with migrations shorter than 200 miles.

Given that approximately 98% of gray bats roost in as few as 15 major hibernacula, natural calamities at any one of the hibernacula could result in the loss of a significant amount of roosting habitat or bats.

Cluster of gray bats hibernating. Image credit: Ann Froschauer USFWS, Public Domain

When hibernation comes, it’s time to mate

Gray bats require two years to reach sexual maturity, and males and females typically hibernate together. They mate in the fall when they begin to arrive at the hibernating caves. Female bats store the sperm throughout winter time, and fertilization only occurs in the Spring when female bats ovulate!

During hibernation, males and females commingle and form large clusters with some aggregations numbering in the hundreds of thousands of individuals. Unlike Indiana bats which stack tightly together, gray bats form loose clusters.

Adult females begin to emerge from hibernation in late March through mid-April to recover energy and nutrients that they need while in gestation phase. Juveniles and adult males emerge at this time of the season as well.

Hibernating gray bat (Myotis grisescens). Image credit: USFWS/AnnFroschauer, Public Domain

Reproduction

During hibernation, females have the double work of storing fat and energy and storing the sperm received in the fall during mating time. When springtime comes, they become pregnant and form maternity colonies of a few hundred to many thousands of individuals.

Gestation takes somewhere between 60 and 70 days, with pups born in late May and early June. A single offspring is born in late May or early June. Newborns typically become volant within 21 to 33 days after birth. While they are flyless, they are carried by their mother.

More than 1 million gray bats hibernate each winter at Fern Cave National Wildlife Refuge in Alabama. Image credit Jennifer Pinkley, USFWS, Public Domain

Food

Gray bats are powerful flyers that hunt over large areas during the breeding season when they feed on flying insects over rivers, streams and lakes and other bodies of water. While Mayflies, caddisflies and stoneflies are preferred, beetles and moths are also in their diet. Most insects are eaten on the wing.

The Asiatic oak weevil is a favorite summertime food, when it is abundant in forested cliffs along rivers.

%20(1)%20(1).jpeg)

Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources bat ecologist counts bats. Image credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters

Conservation Status and Habitat Status

There are dozens of caves throughout the region, but due to human-induced disturbance, fewer than five percent of available caves today are suitable for Gray Myotis to occupy at any time. While the Indiana bat, the northern long-eared and the little brown bat typically roost high up in dead-standing trees and out of reach of humans, gray bats roost on the ceilings of caves and rear their young in places where humans can disturb them through physical touch, noise and artificial lighting.

When caves are disturbed thousands are aroused because of their habit of living in very large numbers, and thousands are lost because there are less than a dozen caves where they hibernate. That is why the gray bat was added to the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants on April 28, 1976.

To help recover gray bat populations, the 1982 Gray Bat Recovery Plan primarily focused on developing a plan to permanently protect summering roost sites and winter caves from human disturbance. As a result, today there are 32 out of 46 summering roost sites in that status. Importantly, this has worked thanks to long-term voluntary landowner agreements, like stewardship plans, conservation easements, habitat management plans or memorandum of agreements, that protect sites in perpetuity.

Protections typically involve posting signage that asks people not to enter caves when bats could be present.There are also permanent campaigns to remind people that every arousal during hibernation is energetically expensive.

Arousing bats while they are hibernating can cause them to use up a lot of energy, which lowers their energy reserves. If a bat runs out of reserves, it may leave the cave too soon and die. In June and July, when the young are still flightless and dependent on their mothers, human disturbance can lead to increased mortality, as frightened females drop their young in the panic to flee from the intruder.

In the past decades, many important caves have been flooded and submerged by the construction of new reservoirs, while other caves are in danger of natural flooding with heavy rainfall. Even if the bats escape the flood, they have difficulty finding a new cave with adequate ventilation, temperature, humidity and amount of light.

Fun fact: two ancient calendars from Mexico, one from the ancient Otomi-Toltec peoples and another from the Maya that have lived in the Yucatan Peninsula for at least two thousand years, refer to bats for the period between October 12 and October 31. The first calendar shows a bat-winged person entering a cave and the other one shows a bat head in profile.

Explore Earth's Bioregions