Meet the ‘i’iwi, the bright red, melodic bird of Hawai'i

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Birds

- Pollinators

- Oceania Realm

- Oceanic Islands

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

A captivating song fills the air in the flourishing tropical forests of Hawai’i. The ‘i’iwi (Vestaria coccinea), pronounced ee-EE-vee, is a bird native to the archipelago that emits musical notes full of wonder and sacredness.

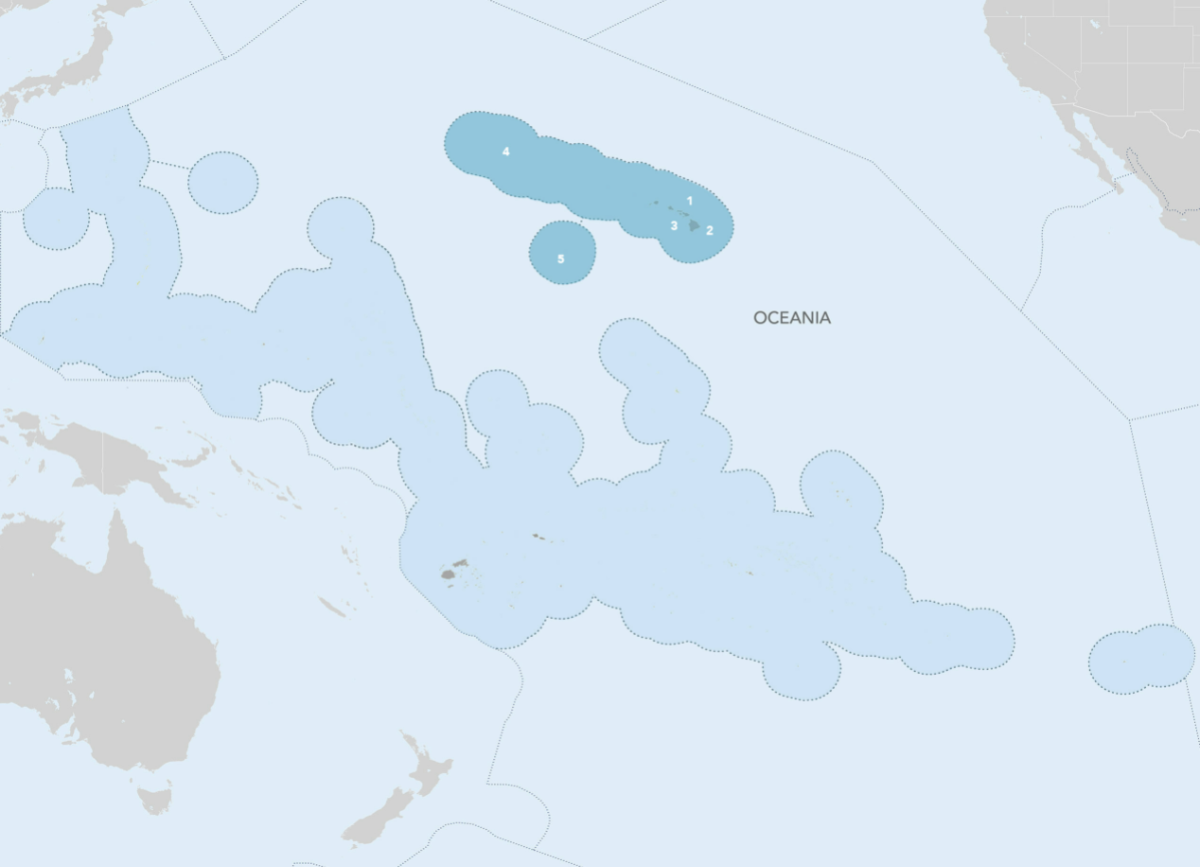

‘I’iwi is the iconic species of the Hawai’i Tropical Islands Bioregion (OC11).

Bright bodies and mating

Against the backdrop of the lush leaves of the forest, males stand out with their red bodies and black wings brushed with a white stripe. Females also have brilliant plumage, an orange head, a red collar that extends backward, and a light-brown body with black wings.

From January to June, the birds pair off and mate. The female lays two to three eggs in a small cup-shaped nest made from tree fibers, petals, and down feathers. These bluish eggs hatch in fourteen days.

The chicks are yellowish-green marked with brownish-orange. In 24 days, the chicks fledge and soon attain adult plumage.

Public Domain

Coevolution with the Hawaiian lobelioid

The beak of the ‘i’iwi is curved and long, an ideal trait for drinking the nectar of Hawai’ian lobelioids, also endemic to the archipelago. A prime example of coevolution, the ‘i’iwi and the lobelioid survive together. The nectar-feeding pollination and seed dispersal directly benefit the honeycreeper’s periodic visits to blooms.

Lobeloids are a group of flowering plants, shrubs, or small trees with flowers characterized by corollas in the shape of long bells, hence the ‘bellflower’ family name. One such species is the tubular flower of the blue ‘ōpelu (Lobelia grayana), which the ‘i’iwi can delicately forage.

The ‘i’iwi will migrate seasonally throughout the islands, visiting bellflower communities as they bloom, taking in as much as 30 milliliters of nectar daily!

.jpg)

Image credit: Courtesy of Mindahi Bastida

Threatened by loss of their flowering food

Sadly, less than 1% of ʻiʻiwi remain on Kauaʻi, while very few have been recorded on Molokaʻi and Oʻahu since the 1990s, and they are no longer present on Lānaʻi. This is correlated to the dramatic reduction of lobelioid flowers since thousands of non-native plant species have been introduced. Of the roughly one hundred or so species that remain, nearly 75% are classified as critically endangered, endangered, or rare.

With every exotic plant brought into the islands, insect larvae mature, reproduce, spread around and predate on the bellflowers and fruits, disrupting their delicate ecological balance.

Image credit: Schmierer, Alan, USFWS

Problems persist with feral animals and farms

Another problematic factor native Hawai’ian flowers face has been feral goats, sheep, pigs, and rats, all of which feed off the partly woody stems and bark of the bellflower tree, which has chewable latex. Since the plants evolved and radiated on the islands without the presence of those animals, adult plants don’t have a defense against herbivory, and seeds cannot germinate on disturbed grounds.

The ’I’iwi is negatively affected by feral and farm ungulates two-fold. First, bellflower communities are too dispersed and with fewer flowers. Second, if they visit grounds where pigs densely populate, they may get bitten by mosquitos that reproduce in rainwater-filled wallows made by the pigs. Mosquitoes inoculate avian malaria, which results in a debilitated immune system.

Strategies to save the species

Conservation strategies that have been considered or are underway to protect the ʻiʻiwi are fencing in cattle grazing grounds, managing grazing lands of feral ungulate, and removing invasive flower species that produce nectar. There is also the idea of increasing native flowering plants in higher elevations so that the 'i'iwi does not have to go into lower-lying areas to access food, exposing them to disease and high mortality.

Giving life and hope to the ʻiʻiwi

In the meantime, the ʻiʻiwi has compensated for its nectar intake requirement by visiting the blossoms of ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha), a very sacred tree.

Hawai’ian people have a high respect for the ʻōhiʻa lehua, as it is said that they are “lovers and that when lehua, the flower, is pulled from the branch of ʻōhiʻa, tears will fall from the sky, as they have been separated.”

‘I’iwi birds will continue to live In the Hawai’ian Archipelago so long as abundant flowering shrubs and trees do, both from the bellflower family and the majestic ʻōhiʻa lehua. Ensuring a healthy state of endemic plants and birds such as the ‘i’iwi, the ‘akepa, and the Hawai’i creeper requires the creation of protected areas managed by local communities and nature lovers while getting private, state, and federal support.

Explore the bioregions