Maned three-toed sloth: a charming species that aids growing trees

One Earth's “Species of the Week” series highlights the flagship species of each of the 844 unique ecoregions contained within Earth’s bioregions.

From sprinting cheetahs to swiftly swimming dolphins and scrambling human commutes, speed is an evolutionary goal across the animal kingdom. Yet, for the maned three-toed sloth, slow has allowed them to thrive on this planet for almost 64 million years.

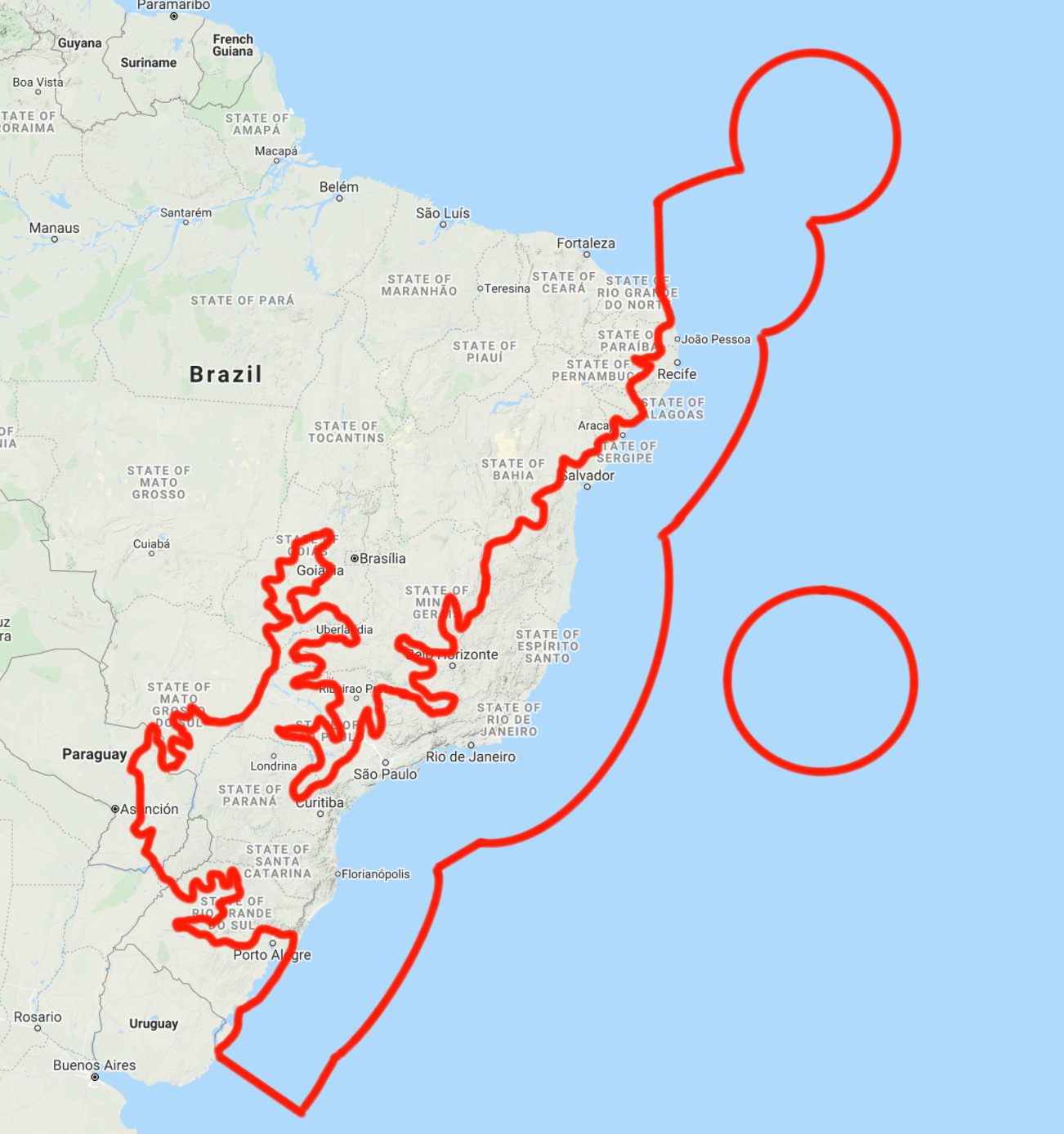

Found only in the Atlantic coastal rainforest of southeastern Brazil, the maned three-toed sloth is one of six species of sloths.

Maned three-toed sloths are the flagship species of the Bahia Coastal Forests ecoregion, located in the Brazilian Atlantic Moist Forests (NT14) bioregion.

Male maned three-toed sloths can measure up to 72 centimeters (28 in) long and weigh up to 7.5 kilograms (16.5 lb). Females are typically larger, measuring up to 75 centimeters (30 in), and weighing 10.1 kilograms (22.3 lb).

What separates the maned sloth from other three-toed sloths is the lack of markings on its face. Long, coarse solid brown fur surrounds a seemingly whimsical smile and gives the maned sloth its name.

This thick outer coat is usually inhabited by algae, mites, ticks, beetles, and moths along their body. In a symbiotic relationship, the greenish tint created by the algae serves as camouflage in the jungle canopy.

As folivores, maned sloths specialize in eating leaves. Whereas most mammals have seven neck vertebrae, they have eight or nine. This allows them to rotate their necks 270 degrees to search for food. Preferring younger leaves to older ones, the maned sloth's diet serves two purposes in maintaining the health of their habitat.

The consumption of newer blooms allows slower-growing plants to become well-established. These plants store more carbon dioxide and produce more oxygen.

Eating buds also allow maned sloths to disperse seeds around the jungle. Individual maned sloths have reported having a home range of 6 hectares (14.8 acres).

Sloths spend almost their entire lives in the trees. Only traveling to the ground to defecate or to move between areas when they cannot do so through the branches. Predators like jaguars, ocelots, and harpy eagles all detect their prey visually, so maned sloths basically move at a pace that doesn’t get them noticed.

They spend up to 80% of their day asleep and primarily live alone. Breeding occurs in the spring and young sloths become independent between nine and eleven months of age.

Deforestation is the major threat to the maned three-toed sloth. Lumber extraction, charcoal production, and clearance for plantations and livestock pastures are all taking part. Today, the maned sloth’s habitat has been reduced to 10% of its original area. It’s up to us to slow down and protect such an essential species and its vulnerable ecosystem.

Interested in learning more about the bioregions of Southern America? Use One Earth's interactive Navigator to explore bioregions around the world.

Explore Earth's Bioregions