The Svalbard rock ptarmigan: A unique Arctic land dweller

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Birds

- Subarctic Eurasia Realm

- Palearctic Tundra

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

Endemic to Norway’s Svalbard and Franz Josef Land, the Svalbard rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta hyperborea) is the only terrestrial bird that lives in the vast expanse of the Arctic archipelago throughout the year.

It prefers high, rocky alpine and tundra regions amidst Svalbard’s glaciers and snow-capped peaks. This subspecies of rock ptarmigan, a member of the grouse family, inhabits the northernmost range of the species’ habitats.

Lagopus means “hare foot,” a reference to the bird’s feathered legs, while the word ptarmigan comes from the Gaelic tarmachan, meaning “croaker,” for its startling cries, which have been compared to running a stick down a picket fence.

Unique adaptations for the cold

Among its remarkable adaptations to Arctic conditions, the ptarmigan's thick, insulating plumage provides protection against the extreme cold.

It is also seasonally camouflaged, with feathers molting from white in winter to brown in spring and summer, allowing the birds to evade predators. The slender-beaked Svalbard rock ptarmigan has a distinctive black eye stripe.

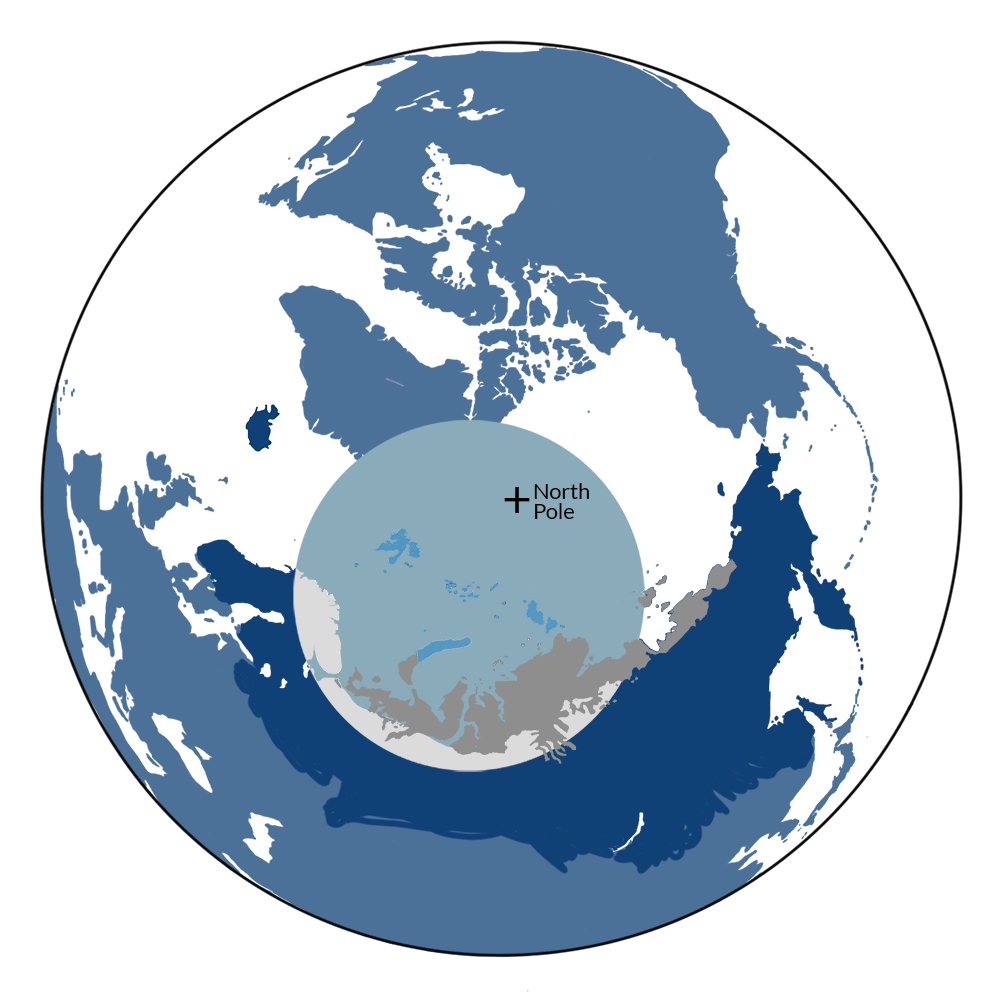

The Svalbard rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta hyperborea) is the iconic species of the Russian Arctic Desert Islands bioregion (PA1) located in the Palearctic Tundra subrealm of Subarctic Eurasia.

Seasonal migratory patterns

Its range is characterized by Svalbard’s extremes: bitterly cold, dark winters followed by brief, intense summers during which the sun never sets—conditions that shape a habitat where only the hardiest species can survive.

Although little is known about the location of its wintering areas or migration routes, the Svalbard rock ptarmigan uses separate habitats in the winter and breeding seasons. In winter, the birds seek relatively snow-free areas with rich vegetation, such as those beneath high cliffs where bird colonies have nested in the summer.

A pilot study using satellite telemetry indicated that they remain in their breeding area from spring until the start of hunting season in September when they migrate to the north and south.

The delicate balance of the food web

Because of the remote habitat in which it lives, the Svalbard rock ptarmigan has only a few important predators aside from human hunters —Arctic foxes, glaucous gulls, and arctic skuas. It has low genetic diversity and appears to be isolated from other ptarmigan populations.

It thrives in an exceptionally simple terrestrial food web representative of a few isolated high-Arctic islands, without small rodents and their associated specialist predators that cause population cycling in other ptarmigans.

Alpine bistort is the most important food source in summer and autumn, followed by various species of meadow grasses and hair grasses. In early winter, purple and tufted saxifrage are the primary food source, and polar willow increases in their late winter diet to build spring fat reserves.

Berries, buds, insects, and their larvae also supplement their diets. Rock ptarmigans maximize the assimilation of nutrient-poor foods with an elongated cecum, a pouch connected to the junction of the small and large intestines; their metabolic needs are partially supplemented by fermentation.

The Svalbard rock ptarmigan is the only terrestrial bird that lives in the vast expanse of the Arctic archipelago throughout the year. Image credit: Harald Olsen, Wiki Commons.

Storing energy in the harsh tundra

Most rock ptarmigans have a limited capacity for fat storage, requiring overwintering birds to forage more frequently. As food availability is lower in its range, the Svalbard rock ptarmigan requires greater fat reserves and has evolved uniquely to gain significant mass.

Fat deposits five times greater than that of other subspecies help them survive during periods of low food availability and can serve as an energy source for up to ten days. Most of the mass gained over winter is in preparation for the spring breeding season.

Breeding behaviors and independent chicks

The cocks return to the breeding grounds around the end of March before the hens arrive in early April. As a small percentage of land constitutes medium to high-quality breeding habitat, establishing and defending their territories is important.

The best nesting habitats are found on high, rugged, wind-blown ridges and south-facing slopes where the snow melts early and vegetation is abundant.

During the brief Arctic summer, the Rock ptarmigan undergoes a remarkable transformation. Males develop striking red combs that erect above their eyes and perform elaborate courtship displays, fanning their tails, spreading or dragging the wings, wagging their heads, bowing, circling the female, and calling.

Females nest among the rocks, laying a clutch of 9–11 eggs in shallow depressions lined with moss and feathers. The hen and her brood leave the nest one to two days after hatching, after which the pair bond between the adult male and female dissolves.

Chicks are born precocial, which means they can soon move independently and feed themselves, fledging fully after 10–12 days but remaining with their mother for 10–12 weeks. Cocks return to the same territory in subsequent years, whereas hens may change territory and partners but always come back to the same general breeding grounds.

Ecological role in the Arctic

Despite its small size, the Svalbard rock ptarmigan plays a crucial role as a keystone species within the Arctic ecosystem, helping to maintain balance within its fragile habitat. Through seed dispersal, habitat modification, and its role as a prey species, it contributes to the health and diversity of its environment, ensuring the survival of countless other species.

Symbolic role across cultures

For peoples of the Arctic, the Svalbard rock ptarmigan has held deep cultural significance. It is revered for its ability to thrive in the harshest conditions and symbolizes resilience, adaptability, and endurance.

In Celtic traditions further south, the rock ptarmigan was seen as a messenger between the human and spiritual worlds, as well as a bearer of good luck and prosperity. Ptarmigans of all subspecies have been revered by the many northern peoples dependent upon them to provide crucial winter sustenance.

Svalbard rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta hyperborea) with summer plumage. Image Credit: © Rafal Nebelski | Dreamstime

Hunting impacts and conservation efforts

The Svalbard Rock Ptarmigan is the most popular of the small game species, with harvests of up to 2,300 birds taking place annually from early September until late December.

While this level of hunting and trapping isn’t known to present a serious risk, population estimates don’t exist for the rock ptarmigan over the whole Svalbard Archipelago. An annual monitoring program established in 2000 has documented low and stable densities.

The effects of rapid climatic changes will require more careful assessment to determine future quotas.

The risks of a changing world

Climate change presents potential risks for the Svalbard rock ptarmigan. This bird is a highly specialized forager, particularly in the breeding season, and it is likely to be vulnerable to phenological mismatch with its preferred food plants in a changing climate. This means that the plants may not develop at the same time that birds usually rely on them most.

While increasing winter temperatures have generally had a positive impact on population growth, negative impacts from changes such as rain-on-snow events have increased winter mortality and caused lower production of young due to poor nutrition.

Also of concern is the substantial increase in the population of pink-footed geese, which now overlap in habitat use, sharing ptarmigans’ key food plants and increasing the possibility of competition.

Climate-induced fluctuations in populations of alternative food sources such as reindeer carrion and breeding geese may impact predation rates. It has also been observed that a warming climate may affect the efficacy of the ptarmigan’s seasonal camouflage.

Despite its extraordinary adaptations to Arctic conditions, the Svalbard rock ptarmigan faces an uncertain future, as climate change threatens to disrupt the delicate balance of its ecosystem, placing this and many other iconic species at risk.

Efforts to protect the ptarmigan and its habitat are underway, but more must be done to ensure its survival. By supporting conservation initiatives and advocating for policies that prioritize the protection of Arctic ecosystems, we can help safeguard the future of this remarkable species.

Support Nature Conservation%20(1).jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=1440)